I have a new book coming out this month and it’s called Jack and Me: How Not To Live After Loss. Not long ago, I would have been too embarrassed to give my book such an obvious plug as that. But that was the old, reticent, self-deprecating me who didn’t feel comfortable engaged in acts of blatant self-promotion. Now that me is dead. Meet the new me: the shameless, self-promoting media slut that I’m trying to become.

It’s hard to believe that there was a time in London society when the pursuit of publicity and self-promotion was considered rather vulgar and regarded as an American practice that no classy English person — especially an English writer — would ever stoop to. (Of course, they did it all the time.) In our age of social media, we’re all engaged in 24/7 self-promotion, with the main product being ourselves.

I have resisted this trend — until now. I’ve never tweeted, blogged or posted on Facebook. Every time I have a piece coming out, I don’t announce it to the world and sit back and count the likes and soak up the compliments. (I just sit and sulk that no one has read it.) I do not Google myself or have a Google alert that would tell me if my name was mentioned in a piece — unlike all the other journalists I know and love. I used to think this made me superior in an old-school kind of way; now I realize it just made me stupid.

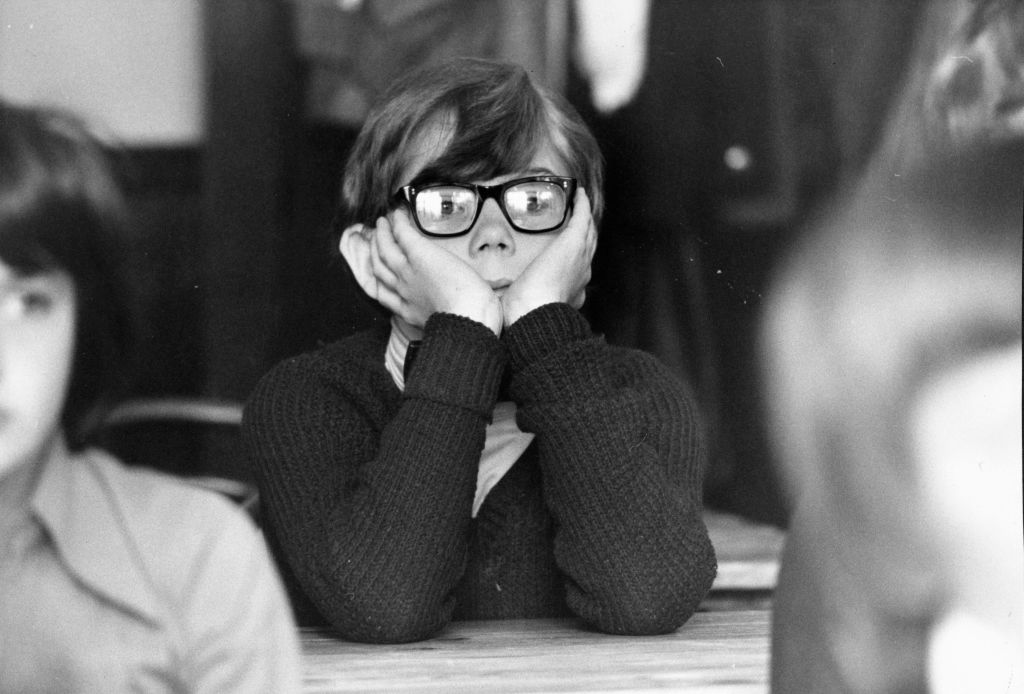

So how did I turn out that way? I blame my parents. I grew up in an artistic/showbiz American family of relentless self-promoters. My father, mother and brother talked about their careers and their latest projects all the time. At dinner my father would read from his latest work in progress (usually a memoir), only to be interrupted by mother (a talented songwriter and poet) who wanted to read us her latest bit of light verse. But both had to do battle against my aspiring-rock-star brother who insisted he play us his latest demo. Meanwhile, oversensitive me sat silently on the sidelines shaking his head in disapproval.

Most of my parents’ dinner guests were equally hungry for the limelight, so that mealtime resembled an episode of America’s Got Talent — but alas, their dinner guests didn’t. My life was shaped by this stream of deluded dreamers and talentless exhibitionists all hungry for their fifteen minutes of fame. I swore that I would never be one of them.

When it came to self-promotion, no one in literary London was as shameless as my dad. In 1987, while promoting his memoir Rebel Without Applause, he used his open marriage, his mistress, my wife (a famous English journalist), celebrities he knew and celebrities he barely knew — to generate media interest. And guess what? It worked. I have boxes of his — and my mother’s — old press clippings. My parents were once the most famous nobodies in London.

I’m now trying to follow in my dad’s footsteps, but it’s not easy being a self-promoting media slut. I’m discovering that the first thing you have to do is get rid of any vestige of embarrassment, sensitivity, tact or shame like my dad did. His efforts were often bizarre. In the hope of getting a profile in Vogue, he wrote to the then young and glamorous editor of British Vogue, “I thought you might like to hear from me since it’s been such a long time since I hit on you. Would you like to do a profile of me?” I don’t think she was amused by his reference to the clumsy drunken pass he had made at her. To the editor of another magazine he wrote to say, “I’ve forgiven you for having me barred from our pub for being boring — would you like to do a profile of me?”

He would call up newspaper editors, TV producers, famous talk-show hosts, top feature writers to suggest they do a piece on him and his new book. When it came to self-promotion, my dad walked a fine line between chutzpah and madness. And when he wasn’t selling himself, he was selling my mother. “Baby,” he’d say, “I’m going to make you a big star.” The fact it was impossible to make a big star out of my mother didn’t ever occur to him.

Of course, I’d get dragged into all this madness. One day my father asked me to write a press release for a book he’d paid to be written about his life. Later in the afternoon my mother called and asked me help write a press release for her new book of verse, and at dinner my brother wanted me to write a press release for an album of his that didn’t even exist.

I remember once I said to my dad sarcastically, “Why don’t you just walk up and down a busy street with a placard that reads: Would You Like to Do a Profile of Me?”

“Hey, that’s a great idea.” he said. At the time I was terrified that he would take my suggestion to heart. Now I’m thinking: maybe it is a great idea after all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.