I’m in the tiny riverside town of Virpazar, in the little Balkan country of Montenegro; and under the white geisha face of a late summer moon I am warily ordering the celebrated local delicacy. It is carp — caught from the nearby, slivovitz-clear waters of Lake Skadar (biggest lake in the Balkans!). But what makes me wary is the preparation. The carp is apparently marinated, and served cold, with boiled potatoes and greens.

Cold slimy fish with hot spuds and spinach? It sounds like some nightmare culinary “specialty” from the old communist bloc (of which Montenegro was once a part, within Yugoslavia). I’m veteran enough to remember a few of these. “Famous” flatbreads that came with rancid lard. “Tasty” chicken necks which turned out to be way more neck, gristle and bone than chicken.

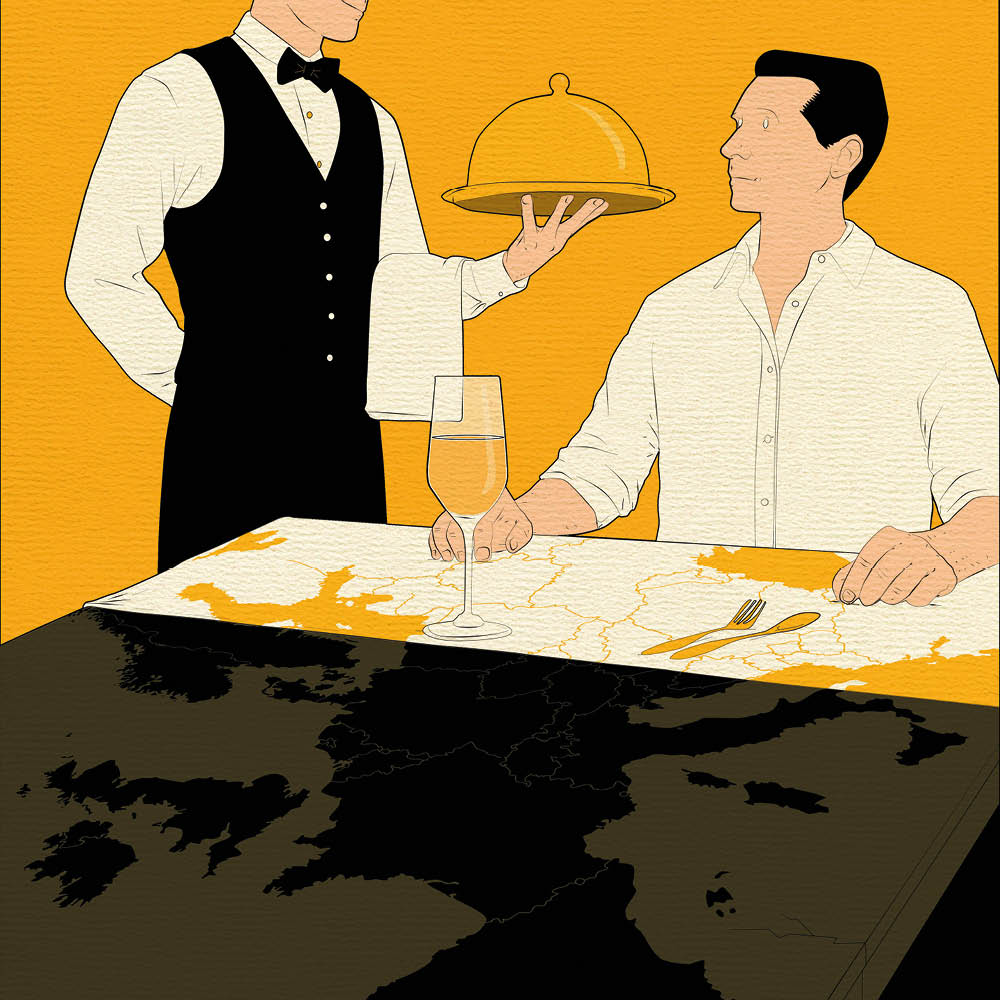

My meal arrives, it smells good, the anticipation rises. And then I take a bite and immediately I know. It is ace. And as I wash down the succulent carp with quite good homemade red wine, I realize that it is, in fact, tastier that any single meal I had during multiple visits to France earlier this year.

Not only that, this is just one of many brilliant dishes I’ve enjoyed across Eastern Europe in recent months — from Poland (pierogi) to Moldova (zama) to Transnistria (borscht), even Ukraine during a war (Odessan cuisine is wondrous). All of them have given me better food than I nowadays generally get in the west. In bomb-sheltering Kyiv I had Italian food better than anything I ate on a recent three-week trip to Italy.

Does this matter? That Eastern European food is now often better — fresher, smarter, tastier, cheaper — than Western European equivalents? Yes, I think it does, because I believe Eastern Europe is now superior in various ways to the West, and the overtaking gastronomy is merely another symptom of this wider evolution. And all my life the opposite has been true; indeed “West is best” has been axiomatic for centuries, so this is the cultural equivalent of the earth’s magnetic poles flipping around.

Another way Eastern Europe is superior to Western Europe is its low crime. The difference when you shift into the east is invisible but palpable. It is like that moment when you drive down France and the north imperceptibly gives way to the south around Valence and the weather becomes reliably good; similarly, as you head east, all at once you no longer have to worry so much about personal crime. In many Polish, Slovak, Slovenian, Hungarian cities your chances of being mugged or robbed or molested are way less than in Berlin, London, Paris, Barcelona, or hundreds of smaller Western cities.

The difference in attitude can make for some remarkable spectacles, for a Westerner. A week ago, here in Montenegro, I watched as an entire table of teenagers, in a large, crowded seaside bistro, abruptly decided to jump in the waves thirty feet away, leaving behind a lunch-table bedecked with all their bags, phones, wallets, handbags. The kids knew they would be there when they got back. Yesterday my hotelier here in Virpazar loaned me a bike without a lock and when I expressed surprise he shrugged and said: “no one steals bikes here.” Imagine that in the UK, Germany or Spain.

Why is Eastern Europe so devoid of the crime that now besets the West? One answer is surely high levels of immigration, which is a Western phenomenon.

This is not to say that immigrants are more likely to be criminal (some stats point the opposite way). The point is that if you have lots of immigrants, lots of coming and going, a country begins to resemble a hotel rather than a home. And if people do not know who is in the next room, they do not feel able to trust the unknown neighbor, and opportunist criminals find it easier to commit crime, without fear of being recognized. That’s why low-trust societies nearly always suffer higher crime than high-trust societies. And that’s not to mention the type of immigration which really does bring crime. There have been no Bataclans in Bratislava.

The list of Eastern superiorities goes on. Thanks to their traumatic history, they are cautious about socialism and resistant to communism, which is handy if you don’t want your nation to go broke. The idea of a Corbyn arising in Croatia is laughable. Equally, because Eastern Europeans have so often seen their identities repressed or even erased, now that they’re finally and proudly free they are not about to yield to cultural cringe, vitiating guilt, or corrosive theories of “white privilege” (compare that with the polls showing a plunge in pride in the UK’s history). Eastern Europeans are basically patriotic in a way we have foolishly forsaken.

Even on the literal street level, Eastern Europeans evince more pride than Westerners: their cities, despite relative poverty, are often cleaner, with less graffiti, less trash, less of a sense of “Meh, whatever.” Krakow in Poland, for instance, is probably better kept than any city in Britain. Central Lviv, in western Ukraine, is possibly more spick and span than any town in Italy.

It is important not to overdo this point. Eastern Europe faces terrific problems. Depopulation and low birthrates haunt nations as diverse as Hungary, Poland and the Baltics (though as natives realize East is possibly best, those human flows might reverse). Crime may be relatively absent from the pavements, but corruption is rife in higher echelons. And then there’s Putin, stalking the frontier like some sociopathic Vlad Dracul with nukes. But Putin also knows he faces countries grimly determined to defend themselves, unlike the flabby, declining westerners.

My supper here in Virpazar is done. I cycle to my hotel and sleep like a Slavic baby and next morning I go on a tour of Lake Skadar with a smart young guide named Miloš. It was he that recommended I try the carp. As we eat yummy fresh Balkan breakfast donuts — priganice — and look at the terns and kingfishers, we move on to politics and I tell him my thoughts. He listens, and says, “You know for many years, we Montenegrins have been desperate to join the EU, but now we look at you… And, for the first time, we are maybe not so sure. By the way, have you tried the priganice with honey and cheese?”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply