You realize western tourists are a rarity when the locals ask to take selfies with you. I was standing under the mammoth ramparts of the Ark, Bukhara’s great palace fortress, when two women came up and asked if they could have their picture taken with me. One was dressed Uzbek-style in a colorful dress with matching trousers and knotted headscarf, the other in a western blouse and trousers. We lined up, beaming, in front of a haughty two-humped camel.

Visiting Uzbekistan is a huge adventure. It’s the heart of Central Asia and the old Silk Road, a land of deserts and oases where you can still feel as if you’re stepping back in time. But it’s also unexpectedly safe, easy, inexpensive and welcoming. At the airport, even the immigration officials were smiling. As the young man I sat next to on Tashkent’s splendid Metro told me in hesitant English: ‘We have a new president now. Things are much better. He wants foreign tourists to come.’

The president is Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who took over in 2016 after 13 years as prime minister. Citizens of dozens of nations can now enter Uzbekistan without a visa, and this concession will soon be extended to American visitors. For now, however, Uzbekistan is blissfully free of mass tourism, and when international travel picks up again there’ll be a small window of opportunity to see this enthralling place while it still preserves a flavor of its exotic past.

In 1920, the Soviets turned Uzbekistan from a conglomeration of khanates into a state. Khiva, Bukhara, Samarkand and Tashkent were wealthy, cosmopolitan oases where merchants trekked across bandit-infested deserts with camel trains to trade everything from silks and spices to slaves in its bazaars. The khanates were taken over by Czarist Russia in the mid-19th century, the khans and emirs reduced to puppets. Uzbekistan finally became independent in 1992. It’s an extraordinary amalgam of very different cultures.

I started my journey in Nukus, a nondescript town in Uzbekistan’s far west. Nukus is so far from anywhere that when the country was part of the Soviet Union, Russian officials seldom bothered to visit. An extraordinary man called Igor Savitsky was able to build up a stupendous collection of banned avant-garde art, produced at a time when Stalin had decreed that only Socialist Realist works were acceptable. The artists had been disgraced, shot or exiled to Siberia, but Savitsky managed to save many of their most important works at great risk to himself. They’re now housed in a museum that’s been dubbed ‘the lost Louvre of Central Asia’.

From Nukus, four hours of bumping along pot-holed roads through desert dotted with scrub brings you to the spectacular rose-tinted walls of Khiva. I had brought clothes suitable for a Muslim country but quickly discovered there was no need. As Ali, my Khivan guide, said: ‘Nowadays Uzbekistan is theoretically 90 percent Muslim, but most people don’t practice.’

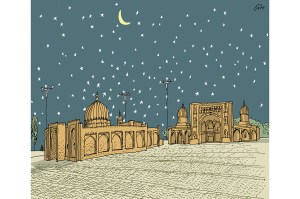

Khiva, a Unesco World Heritage site, is breathtakingly beautiful. Everything is perfectly preserved: the Khan’s palace where he lived with his wives and 40 concubines, glorious tiled minarets, dazzling blue-domed mosques, madrassas and plazas. But it’s empty and feels a bit dead. To find the life of the city, you have to explore the backstreets outside the city walls, where old women sit on the steps outside their houses or visit the cemetery with its dome-shaped tombs. There I found an outdoor restaurant where I dined on Khivan green noodles and skewered sticks of mutton cooked over charcoal.

From Khiva I crossed the river Oxus and followed the Silk Road for another six bone-jarring hours. At a roadside cafe I snacked on rounds of delicious fresh-baked bread. I passed donkeys, camels, trucks laden with hay with people riding on top and square mud-walled houses.

Finally I reached Bukhara. I’d happened to arrive just as the city was celebrating its annual Silk and Spice Festival. People had come from miles around, dressed in their best. Musicians played lutes, fiddles, tambourines and drums, singers belted out folk songs, dancers performed intricate hand movements and a jester in a multicolored coat pranced about. The crowd danced, too, while an old man in a white turban leaned on a stick, observing.

Bukhara has all the beauty of Khiva, but it’s a living, breathing town, bustling with people and bazaars. Bukhara’s domes are not blue-tiled but of pink brick, configured in geometric designs reminiscent of M.C. Escher’s drawings. At the center of the city is the Kalyan minaret, which dates from 1127, so tall that when Genghis Khan put his head back to look at it, his helmet fell off and he decided to spare it. The Ark, the emir’s palace, is a mammoth fortress with concave mud walls, impossible to climb. It broods over the city still, as it did in the days when miscreants (and the odd unlucky British officer) were executed in the plaza outside it. But the real heart of the town is the Lyabi Hauz pond, shaded by mulberry trees, where people sit around all day drinking tea out of blue-and-white ceramic cups.

From Bukhara we left the Royal Road and took a roundabout route through the steppes and across the mountains to Samarkand, crossing a much more fertile region, past apple orchards with many towns and colleges. At Shahrisabz, where Uzbekistan’s great hero Timur (Tamburlaine) built his summer palace, we stopped for lunch at a lovely place with a shady courtyard where doves with luminous green tails ran about.

Today — shades of Ozymandias — little remains apart from a colossal portal, above which are inscribed the words, ‘If you challenge our power — look at our buildings.’ Snow-covered mountains rise in the distance.

[special_offer]

We drove towards them up a sweet valley to the top of the pass where there’s a view of the Pamirs, and on to Samarkand.

While Bukhara feels tightly medieval, Samarkand is a sprawling city. There are many wonderful things to see, among them Registan Square with its staggering madrassas covered in tilework; the observatory of Ulugh Beg, Tamburlaine’s grandson and a famous astronomer; and an amazing complex of mausoleums stretching up a hill, each decorated with ornate tilework in different styles.

But Samarkand also has its secrets. In the middle of a line of gift shops, alerted by my guidebook, I spotted a wall with a door which looked as if it led to a private house. I stepped through, like Alice going down the rabbit hole, and found myself in the old city, a maze of streets with hills in the far distance.

The smell of baking bread led me to a hole-in-the-wall bakery where a young man in a vest was pounding and molding rounds of dough and throwing them into a beehive-shaped oven. It seemed to embody all the magic of Uzbekistan with its alluring mix of east and west, past and present.

This article is in The Spectator’s July 2020 US edition. Subscribe here to get yours