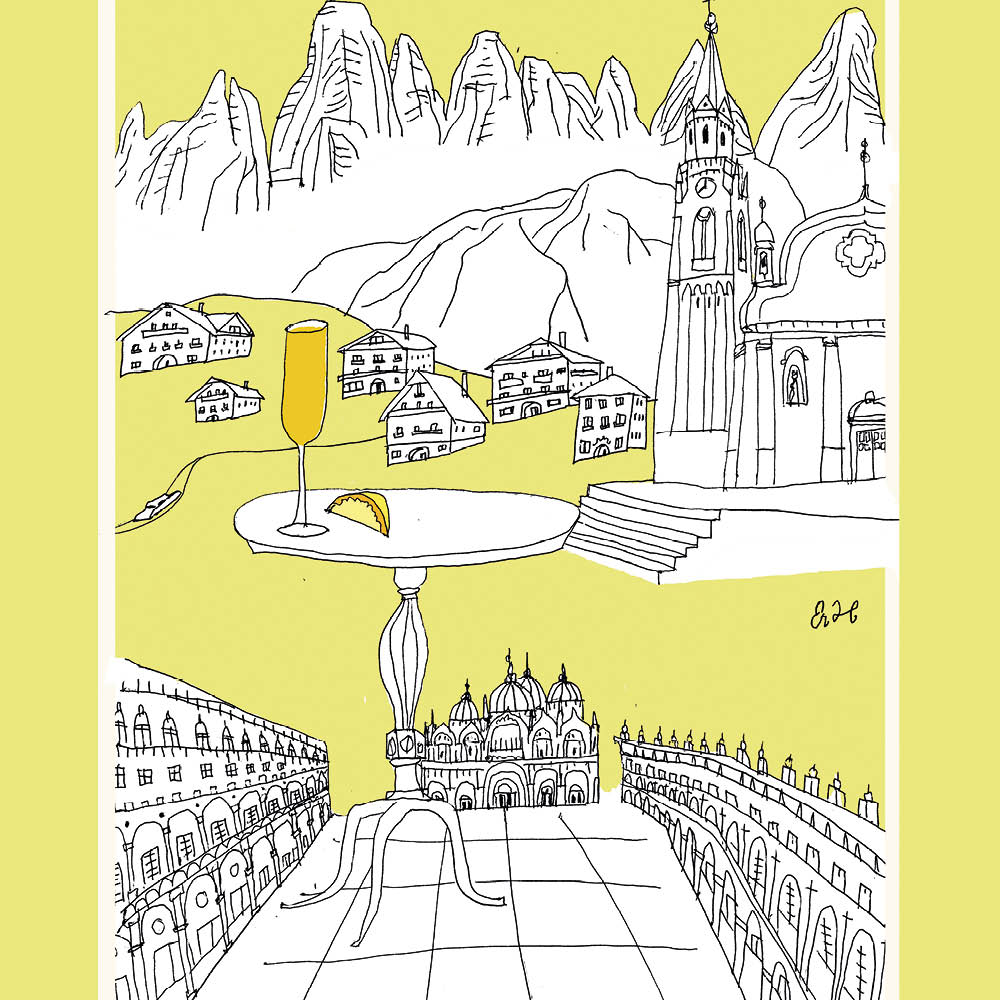

Those who have visited Venice in the summertime will have witnessed the masses who descend into the heart of the labyrinthine islands, clogging their historic stone arteries and beautiful atria in a gormless and sclerotic trance. Meandering along the canals can always lead to some duomo or piazza that merits a standstill and an upward gawp. If you’re at all like me, after sweating through those tight streets with other tourists, one day certainly feels like enough.

So it went on my recent visit. After popping my head in for as much of the Biennale that was still on display, a Bellini at Harry’s, lunch at Staffa and an inspiring visit to the Fondazione Querini Stampalia, I decided to get in the car and leave.

The Fondazione Querini Stampalia, a five-minute walk from San Marco, offers a refreshing contrast between its old collection and modern exhibitions. But beyond its tastefully balanced curation, the house is one of Carlo Scarpa’s masterpieces. Both the renovation of the institution and the garden were designed by the architect (1906-78) and completed in 1963.

Perhaps one of his most notable designs, the renovation of this sixteenth-century palazzo embodies the Foundation’s ambition to balance old and new, while boasting elite urban architectural design.

Spurred on by Scarpa’s forms, I sought to gorge myself on his work. Once out of the city, it was north to the mountains. San Vito d’Altivole is a small town in the Treviso region, close to Asolo. There, extending inconspicuously out from the verdurous roads and low housing of the town, is a cemetery which features another Scarpa masterpiece, la Tomba Brion.

It was commissioned as a memorial and tomb for the Brion family in 1969 and displays some of the most deliberate and alluring details in post-modernist architecture. Scarpa’s concrete structures emerge from pools and are adorned with subtle features of gold and pearl. The sense of purity and serenity in the place is almost overwhelming.

Around twenty minutes further north lies a third treat: the Scarpa Wing of the Museo Gypsoteca Antonio Canova in Possagno. Within is found a vast collection of Canova’s plaster casts — the gypsum referred to in the museum’s name. The sculptures stand, sit and perch, housed in the epic design of Scarpa’s extension. The halls are a hybrid, with harmonious classical geometrics and playful modernist patches that makes one consider just how iconic Italian style can be.

Onward from those great structures, I headed for the hills. I detoured briefly to swim at the Laghetto di Camazzole, known locally as the Maldives of the mountains, in whose cold, aquamarine pools you can grasp anywhere at the Brenta riverbed and collect a handful of live little clams. Bassano del Grappa, Asolo and almost any point on the hills of Valdobbiadene merit a stop to enjoy both the local cuisine and, of course, the Prosecco.

Few might consider the Alps a summer destination. Even most of the hotels leave their ski-in-ski-out advertisements up on their booking pages. So it was curious to encounter quite so much human- and motor-traffic on the way through Cortina, a destination known to any European ski enthusiast or fan of Ripley. Just as well that I had decided to stay at Hotel La Perla in Corvara in Badia, South Tyrol.

Despite the town being far less populated than it might be in January, we arrived to find a party for the guests and were warmly welcomed to a full room by owner Mathias Costa and his wife and daughter.

Clad in traditional Alpine attire, Costa introduced himself in both German and Italian. He frequently circled the room topping up the Champagne glasses of his guests, inviting them to pick at the array of canapés before moving on to their dining experience at one of the hotel’s five restaurants.

Food is one of the focal points of the people in this mountain area, perhaps as an extension of Italian culture. There is a strong sense of hospitality along these could-be perilous, remote mountain slopes, and its importance is stressed as you move around La Perla, where subtle kitchen smells waft through fresh mountain air and blend with the scent of the chalet’s pine walls. Aldo Fornasari, chef at Berghotel Ladinia in Corvara, took us out one morning on the verdant Alpine slopes. As he shepherded us up and across the hills, he drew our attention to the variety of edible herbs and medicinal plants traditionally foraged in the region. Wild carrots, mountain cumin, borage and dandelion all have their seasons on these grassy inclines, but after nibbling at what we could and filling a tray basket with an assortment of other leaves, we were directed to his kitchen, in which his team had set out some other ingredients.

Mixing eggs, old bread, milk and cheese together with handfuls of the wild spinach we had collected, Aldo described the nostalgic connection the region had with the dumplings we were manufacturing. Canederli or knödel are a Tyrolean staple and hold a permanent place on Aldo’s menu. They are rustic hand-formed dumplings, gently rolled with the palms and then plopped straight into boiling water.

We enjoyed ours with a drop of wine before being treated to the dessert that cemented his spot on the culinary map for the region: sedano di monte, or “mountain celery,” ice cream.

If the gastronomic delights of the region have a wine pairing waiting for them anywhere, it is likely in the cellar at Hotel La Perla. The hotel stocks an impressive collection of more than 30,000 bottles in a multiroomed basement that comes with a shrine to the delicious red Sassicaia and a proud sommelier to guide you through the tunnels. You’ll certainly save time following his suggestions at dinner rather than attempting to choose from the pages of their biblical wine list.

Thankfully, the guilt of overindulging in the hotel’s offerings can be alleviated by any of the lengthy hikes you can take out of the front door. An impressive network of cable cars will take you up and across to find views of the sharpest peaks and of glass-like lakes. The coniferous forests and the stone cliffs appear as if drawn in the clarity of the summer sunshine — the tranquility a stark contrast to the bustling streets of Venice.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply