If you tell friends you are going to Kyrgyzstan, they look blank, or think you are talking about Kurdistan, although the two are 2,000 miles apart. If you get the choice, choose Kyrgyzstan.

Like so many, I first learned of the place because of Alexandra Tolstoy: writer, adventurer, horsewoman and cousin of the author of War and Peace. She discovered the romance and beauty of the place for herself when she rode 5,000 miles of the Silk Road by horse and camel in 1999. Since then, she has ridden in Kyrgyzstan most years, taking parties of 12 or so into the lower slopes of the vast Tian Shan mountains, the highest range west of the Himalayas. Blonde, fearless and always elegantly turned out, she leads. We follow. As Kyrgyzstan’s global ambassador for tourism, she tends to get what she wants.

As soon as I and a couple of early arrivals reached the capital, Bishkek, Alexandra swept us off to meals with the deputy prime minister and a colleague who heads Kyrgyzstan’s equivalent of DoGE. We were given places of honor for the splendid 80th anniversary marchpast celebrating the end of World War Two.

In communist days, Kyrgyzstan was a “republic” of the Soviet Union. It retains close ties with Russia. Most people, including Alexandra, speak Russian there in their daily lives. To the east, it borders China. With only seven million people, it treads warily between the two great powers. In Silk Road days, it was a borderless collection of 40 nomadic tribes (kyrgyz means 40) through which many traders passed. Today, it is a democracy, but a tactful one.

But politics was not our concern. We were headed for the open road, the hills, the horses. These, be warned, require a slow 12-hour bus journey from Bishkek. At last, the bus passes through a long and smelly tunnel and the Sary-Chelek region, the world you seek, lies – or rather, towers – before you. There the highway is frequently blocked by herds of goats, cattle, sheep, and the region’s famous horses. Men and boys wear the traditional white felt al-kalpak hats, sewn together from four parts to mimic the shape of a Kyrgyz mountain. They ride beside their herds, short whips in one hand, reins in the other. I spotted one young rider coming towards us whose whip looked different. As he approached, I could see it was a stick carrying his phone: even in Arcadia, the selfie.

May is the best month if you seek flora and fauna. The lower peaks have greened up, but the distant, higher ones are still capped with snow. One dreams of riding up over them but, thank God we didn’t (it would be incredibly chilly, dangerous and adverse). Instead, we rode the foothills, past turbid gray mountain rivers and among walnut forests and wildflowers of the most vivid beauty.

At dusk, we finally reached our first camp. Across the torrent beside our tents loomed a pinkish cliff, weirdly shaped and surmounted by a single juniper tree. Literally one minute after we had stowed our bags, a thunderstorm engulfed us and lightning flashed round the hills.

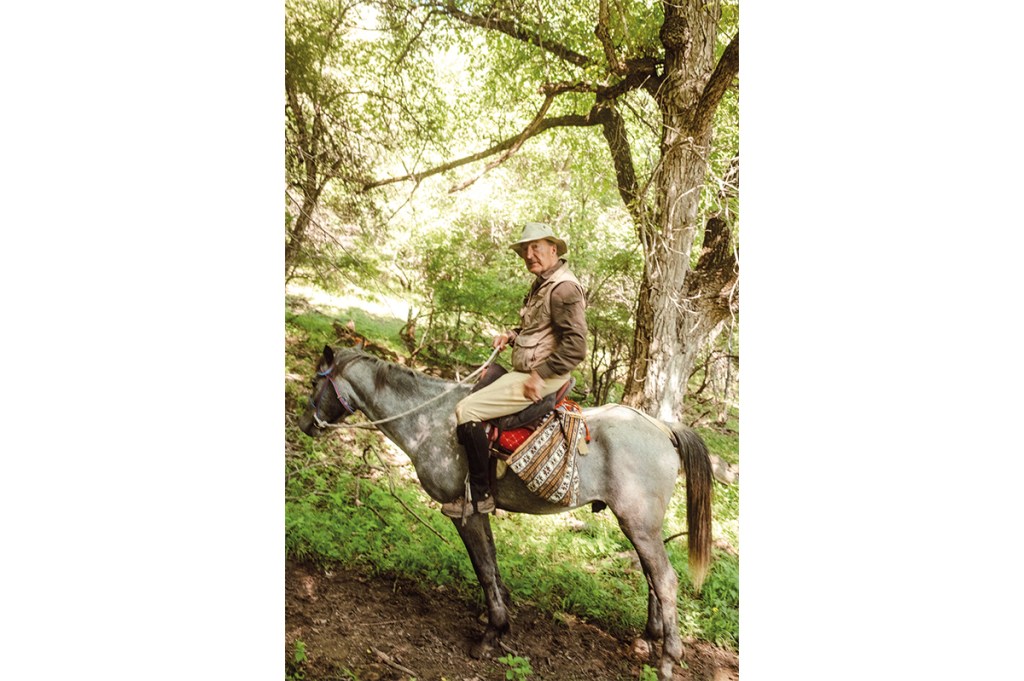

Tolstoy discovered the romance of Kyrgyzstan when she rode 5,000 miles of the Silk Road by horse and camel

Once the rain had eased, we gathered in the common dining tent. This is real camping, not air-conditioned luxury, and it has camping’s inconveniences, such as being cold at night (hot water bottles are sensibly provided). Rather than struggle with a pan of hot water and a tiny mirror, I grew a beard. But the quality of the local dishes cooked for us, and the kindness of the people serving them, made us feel that if we were roughing it, we were doing so royally. There is almost nothing I like less than western donuts, but the local ones – boorsok – are a different order of creation. I fell asleep to the sound of the scops owl, which experts describe as “a single, drawn-out whistle.”

The next morning, we met our mounts. Mountain districts are often home to tough, rough little ponies, but these were handsome beasts of about 15 hands. They all come from the same village and are almost all stallions. Don’t let one rub noses with another: it starts a fight. Also avoid the mares in season who wander the hills and whinny invitingly to the stallions.

Once traveling, the horses are thoroughly reliable, sure-footed and unusually comfortable to ride. My own dear creature, an iron-gray chap with a pretty face like a Welsh pony, was called Kokmanchok, which means “emerald.” A typical day’s journey was five or six hours, breaking for a picnic lunch. No one suffered from chafing. My three friends and I were quite experienced riders but some of our congenial party of a wide age range were not and might reasonably have feared the riding itself. It is fine: follow the leader, don’t look down when the river roars 100 feet beneath you, and all will be well.

The guides inspire confidence too. The 12 of us rode with five men, all from the village of Kara-Suu (Black Waters), who care for the horses. We were led by Djuma, a veteran over 60 who knows every inch of the way. Kokmanchok’s owner was called Melis, which dates him from the Cold War era: Melis stands for Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. The men are fit and agile. Their favored pastime when dismounted is to launch themselves off rocks, pretending they can fly.

Alexandra sequences the journey to unfold the full variety of scenery. The first day – sunny but not scorching – took us up in mainly open country so that we could survey the widest view. The second plunged us into the mainly deciduous forests, varied here and there by the Tian Shan pine unique to the region. The third delivered us to a camp by a remote, roadless lake (at a perfectly survivable temperature for swimming), where the horses were hobbled and left to wander the empty hills for collection in the morning. Before that, we could gallop in the wide pastures.

By now, we felt right in the heart of the place. The next day, we entered the national park, the only part of the country – except for village smallholdings – which is fenced. Here is the full abundance of nature which grazing inevitably reduces elsewhere. Every field was filled with flowers and plants which, in the West, appear only in gardens: dwarf species tulips, peonies, alliums, miniature irises, yellow poppies and fennel.

What in America might be a ball, in Kyrgyzstan is the headless body of a goat

As for birds: blackcap, common rose finch, blue laughing thrush, Indian golden oriole, Hume’s warbler, hoopoe, sand martin and, which woke me by the lake, a cuckoo. The commonest sign of nearby human habitation is beehives.

On this fourth day, Djuma showed us what you could call his summer home – just a tarpaulin hanging from a branch under which he and his family sleep. By day, for the six weeks of harvest, they shin up the walnut trees, and shake them – “like monkeys,” as Alexandra put it. On a good day, the family brings down 18 pounds of nuts.

After our second night by the lake, this time woken by a Scottish bagpiper friend who had somehow found his way to the camp the night before, we set off for the mountain pass. We had been told we would have to dismount before the top. I had feared leading my horse along the edge of a precipice. False alarm. Djuma rode ahead, and then all the other horses, riderless and unled, obediently followed him. We riders plodded safely up on foot behind them.

At the pass, 8,000 feet up, we could look back to the gleaming lake in its relatively gentle setting and forward to the jagged, still snowy peaks ahead. As we did so, our piper decided to start skirling – a sound which attracted seven lammergeier vultures who presumably thought they were hearing the screams of a dying mammal which could be their lunch.

Descending, we found ourselves on a flat field, near where a mountain stream dispersed into a lake. “That’s the pitch,” said Alexandra. Ready for us was a match of the local sport, kok boru. What in America might be a ball, in Kyrgyzstan is the headless body of a goat. Two teams of riders compete to bend down while staying mounted, snatch the unfortunate goat from the ground and dump it in the rival goal. As they gallop forward, their opponents, carrying whips, try to wrest the goat from its place between a Kyrgyz saddle and a Kyrgyz thigh.

No protective gear is worn and men who fall off have somehow to avoid the hooves of the melee. Djuma’s seven-year-old grandson trotted bareback round the edge of the game, longing for the day he can take part.

Our guides made up one team, and local men the other. Against precedent, we narrowly lost. But, perhaps because we were guests, we were presented with the goat’s now tenderized body. It made a delicious kebab in our camp that night.

Before we could rest, we had to drive off a sex-mad donkey who was noisily pursuing a female of the species through our line of tents. I hope I have said enough to show that this journey was unique, vivid and, well, Tolstoyan.

The author traveled with Alexandra Tolstoy Travel in association with the Ultimate Travel Company.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply