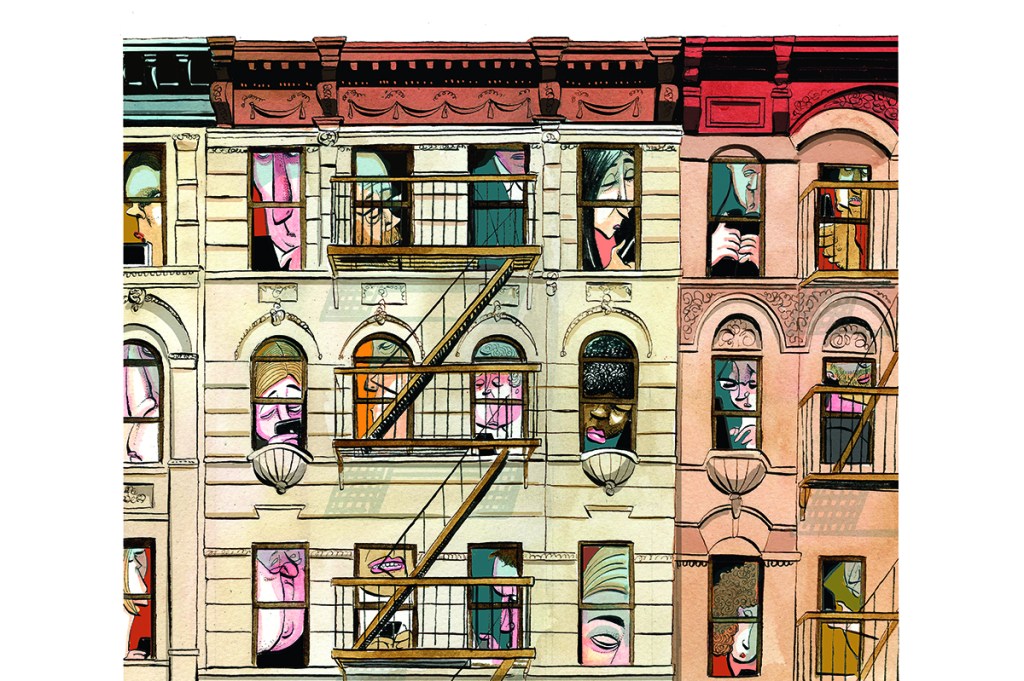

Like most people, I have had a rotten 2020. I have missed my family. I have missed my friends. My work has been disrupted. With that said, I do not live alone. I have a job. I have my health. Really, I’m among the lucky ones. People who have endured isolation, unemployment and ill health have had a far more miserable time. In such a gloomy period, it’s natural to think about the consequences for people’s mental health. Lockdown-induced loneliness and virus-induced stress seem liable to have lasting effects. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have found that ‘symptoms of anxiety disorder and depressive disorder increased considerably in the United States’ during the summer compared to the summer months of 2019.How serious is the problem? Let’s consider the most serious of questions: have rates of suicide risen since the start of the pandemic? The evidence is mixed. Dr Jeremy Faust argues in the Washington Post that in Massachusetts, which has had some of the longer, stricter shutdowns, they have not. According to CNN, however, there has been a rise in suicides among soldiers, ‘raising questions about whether troops feeling isolated due to the coronavirus pandemic may be a contributing factor’.Suicide ideation, especially among younger adults, has increased and suicide ideation is often, if by no means always, associated with suicide attempts.The severity of the psychic consequences of this year remain to be seen. The effects of unemployment, bankruptcy, anxiety, loneliness and, of course, ill health, do not appear at once. Only years into the future will their full scale be known.Yet we can predict some things. A Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health study found ‘every economic/financial crisis since 1970, except the European Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis in 1992, led to excess suicides in developed countries.’ With all due respect to the survivors of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism crisis, I am not going to bet on 2020 being a rerun of 1992.What concerns me most, however, is social isolation. This is not a new phenomenon. In some senses, COVID-19 has led to a kind of reductio ad absurdum of modernity. Lockdowns, and voluntary social distancing, devastated Main Street businesses that were already being strangled by Amazon. Young people were prevented from forming relationships which they were already increasingly less liable to form. Care homes, as I wrote last month for The Spectator, became hellish having been, well — somewhat less hellish.None of this is meant to diminish the awfulness of the year. If I had a slow decline in brain function, it would not make me more comfortable with a bullet in the head. But it’s worth keeping in mind that our societies have problems which precede 2020. Two of those were rising rates in depression and suicide and, much as I grant that statistics for the former phenomenon are unreliable and prevalence of the latter depends on access to effective means of death as well as on your actual problems, it was hard not to connect it with increased social isolation, which we know to be linked to ill health and suicide.If this was a grave problem before 2020, it must be far more so now. Again, social frustration is not the same as social isolation. Not seeing our friends as much as we would like is sad but not, for most of us, a crisis. For people who were already lonely, though, and have been denied their few sources of human interaction, as well the chance of improving their social circumstances, it must have been tragic — and, as I know from unpleasant personal experience, our thoughts can degenerate when we are alone.This might have sounded overdramatic in April, but it seems less so in November. Self-reported loneliness has doubled among older adults and risen significantly among the young. This should be a wake-up call about the scale of loneliness in mass society. As much as we should be trying to protect the physically vulnerable, that does not excuse neglecting the spiritually fragile.

[special_offer]

I worry that health experts overlook this phenomenon. Take a post like this, from Dr Krutika Kuppalli of the Stanford University School of Medicine. ‘I feel like there is this perception that once we have a [vaccine] life will go back to normal,’ she writes. But:‘Life will not be like it was pre-COVID. Even after we have a vaccine you will still need to use good hand hygiene, maintain physical distance, avoid crowds and wear masks.’Sure, life will not go back to being exactly the same. Personally, I hope I will have better hand hygiene. I will stop thinking it is to my credit that I go to work even when I’m seething with rhinoviruses. But with all due respect to Dr Kuppalli’s medical expertise, you cannot expect people to keep ‘social distance’ indefinitely without going mad. We are social animals. We — or, at least, most of us — thrive on togetherness, and touch, and fellowship. (As an aside, but not a trivial one, I think experts like Dr Kuppalli should be careful not to demand such exhausting sacrifices of people that they do not treat future, perhaps far more dangerous diseases with the seriousness they deserve.)That’s not to suggest that the virus itself is not a cause of stress, and exhaustion, and grief, or to claim that deaths could have been minimized while life continued with blissful, undisturbed normality. The least that can be done, however, is not unnecessarily inhibiting community life. Policy-makers can encourage al fresco dining in California, subsidize air purifiers in North Dakota and enable old people to meet their families in the airiest, most open places in Arkansas. But stifling people’s social existence might have longer, deeper consequences than we know. We were lonely enough already.