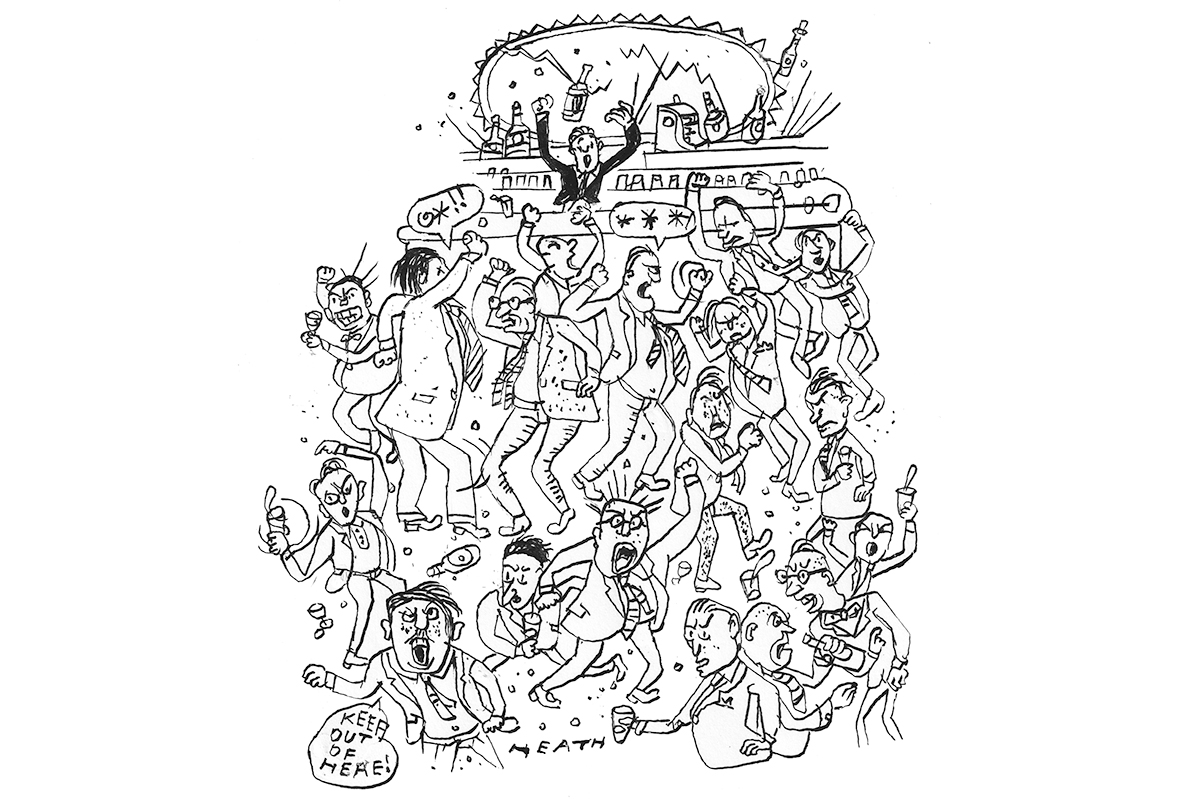

I often argue that, in theory at least, well-made cocktails are indisputably better than wines costing 20 times more. My argument runs as follows. In making a cocktail, you can mix, in any combination you wish, any of the liquids known to humanity. In making a wine, you are stuck with using grape juice harvested by grumpy Frenchmen from scrubland east of the Gironde. Mathematically, the odds that the best drink you can generate derives only from a few bunches of such grapes is so small as to be infinitesimal. Besides, almost no one drinks grape juice, and nobody has ever seriously tried to sell non-alcoholic wine. If it really tasted all that good, these things would have taken off by now.

Yet one reason people like wine is because our judgment is highly relative. When you say ‘That’s a great glass of wine’ you aren’t saying ‘Of all the liquids I could have drunk, that one wins gold’. Instead you are affirming that, compared with most of the wine you have drunk in the past, it is notably more pleasant than average. I drink and enjoy wine myself. I am simply arguing that its success as a drink is more down to peculiarities of human perception and phenomenology than a property of the drink itself. Wine has acquired a value detached from wider comparison.

This notion that our conception of value is often arbitrary, comparative and socially constructed seems plausible. And, reading the work of anthropologists such as David Graeber and Gillian Tett, it seems to be more important than I thought. Both anthropologists explain how arbitrary conceptions of value become deeply embedded in the thinking of institutions and businesses, where they take on a bureaucratic life of their own.

Often a narrow pursuit of efficiency comes to stand in for more subtle definitions of value simply because efficiency is an easy goal to chase, and its rules universally understood. If you have ever wondered why so many company websites hide their phone number, it is because the immediate saving through reduced phone calls is more measurable than the ultimate cost in lost sales or mistrust. No small shop would snub a customer to save money — but large firms frequently do. As Roger L. Martin argues, we prize and reward the manipulation of quantities more than the appreciation of qualities. Witness the vast expansion of people employed in administration.

We now have an opportunity to significantly improve medicine. But this efficiency doctrine will cause us to mess it up. Yes, it is silly that to visit a doctor with a simple query I must phone for an appointment and then wait in a room with a lot of ill people. Telemedicine has enormous potential. But only if is balanced with a corresponding increase in the quality of face-to-face contact at times when it makes a difference.

The real value of technology should be in automating what can be automated and making more personal what needs to be personal. If you install an automatic door at a hotel, you do not fire the doorman — you use him to make a fuss of customers in other, more valuable ways. Likewise I don’t want to talk to a human to learn my bank balance, but I would like a human to help me open a business banking account (I tried this recently — it was like dealing with the Stasi).

That’s how technology should work. But the efficiency doctrine won’t allow it. In a sensible world your doctor would deal with you online five times out of six and visit you at home on the sixth occasion. I suspect people would love this. Unfortunately it won’t be allowed to happen. Such a move would require the appreciation of things beyond the accepted frame of comparison. It’s also why you can’t enter a Pina Colada in a wine tasting.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.