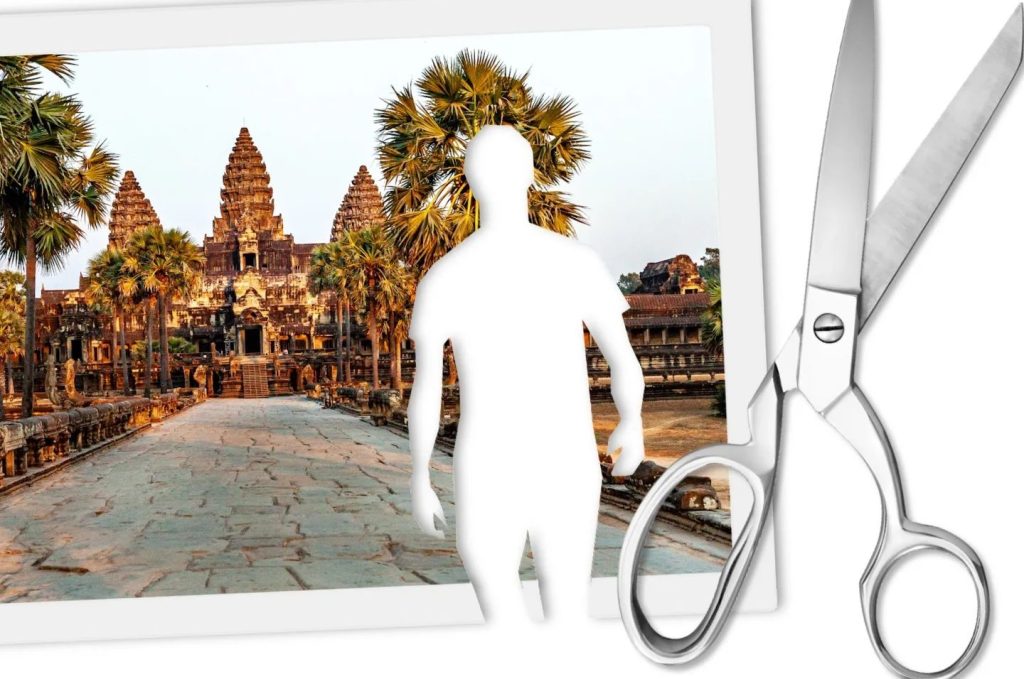

A few months ago, I visited Angkor Wat, the majestic temple in present-day Cambodia that once stood at the center of a vast empire. As the five towers of the palace came into view, I was, despite the intense heat, fully immersed in the beauty of the place. I imagined how excited a visitor from a faraway land in the 12th century, full of anticipation for a meeting at court, would have felt arriving at what was then the largest settlement on Earth. And like that imaginary visitor, I felt propelled forward, impatient to cross the moat that separated me from the edifice, to get a closer look.

At that moment, I heard a confident American voice. “Excuse me,” the man shouted, as he crouched on the floor, phone in hand. “I’m taking a picture.” I took a few steps back, joining about a dozen people waiting patiently in the scorching sun for the man to take a photo of his wife. As I stood there, I kept thinking: “Why are all of us doing this?”

Should everybody be able to visit beautiful sites without having to dodge the photos others are taking?

Much the same happened in other towns and temples I visited on a recent trip to Asia. Whether in Seoul, in Hanoi or in Luang Prabang: at a dozen beautiful sites, it felt as though half the visitors were focused on taking pictures, while the other half avoided photo-bombing them, reduced to walking around in elaborate patterns that would, if you traced them on a map, resemble the perimeter of a badly gerrymandered electoral district.

The question of whether we should feel the need to stop what we are doing when other people are taking a photograph has become an ever-present dilemma. It is a question with admittedly low stakes but one that seems to me to have, if not exactly a moral, then a certain modicum of aesthetic significance. It goes to the heart of how each of us experiences the world and what kind of engagement with our physical surroundings we should collectively prize.

Should people be able to take a picture of their loved ones without running the dangers of photo-bombing? Or should everybody else be able to visit beautiful sites — or, if they happen to live in a city that attracts a lot of tourists, go about their daily life — without having to dodge the videos and photographs that others are taking?

One approach to thinking about this is a term I have loved since first hearing it: obsolete design. It has, for instance, been decades since computers used floppy disks. And yet the button you click to save a file remains a depiction of that long-gone object. The save icon is a prime example of obsolete design.

It seems that there are also forms of obsolete behavior. Before the advent of digital photography, film was expensive. By walking through your picture, a stranger would make you waste a precious resource. Worse, unless you happened to be using a Polaroid, it was impossible to check on the spot how a photo had come out. You might not even realize that some stranger had ruined your picture until you got the film developed — at which point it would be too late to take it again. All of that provided a strong reason for people to go out of their way to avoid inadvertently photo-bombing each other.

Today, virtually everyone uses digital photography: taking a picture on an iPhone is free. If some stranger is visible in the first picture you take, you have only to wait a few seconds until they move on and take another one.

The risk of a bad surprise has also been eliminated. It now takes minimal effort to inspect your photograph on the spot. So you can make sure you’re happy with what you’ve got well before you fly back home.

At the same time, the advent of digital photography has made it harder to avoid interfering with others’ pictures. Because it has become so much cheaper to take and share pictures, the average person takes many more videos and photographs than in the pre-digital age. Even if the number of visitors to a famous tourist spot or a particularly cute café has not grown in the past few decades, the number of people who are taking pictures at any one time has skyrocketed.

In the past, there were real reasons why we should all try to avoid interfering with each other’s photographs. Since then, the cost of being photo-bombed has fallen, and the cost of avoiding photo-bombing others has risen. The social norms which developed in the age of analogue photography have become a form of obsolete behavior in the age of the iPhone.

What’s more, besides the practical case for photo-bombing, there is also a more aesthetic case to be made. As I felt on my recent travels, the ease of taking pictures creates a great temptation to experience any sight, no matter how awe-inspiring, mediated through the small screens of our smartphones. When I saw beautiful temples or ancient ruins, I knew full well that I would, if I ever needed a visual reminder of them, be able to call up perfectly composed, professionally taken photographs with a quick Google search. And yet I could not resist the temptation to interrupt my contemplation of their beauty to take my own mediocre snap. The ubiquity of digital photography makes it much harder for any of us to marvel at the wonders of the world.

It would be bizarre, impractical and authoritarian to forbid tourists from taking pictures at beautiful sites, just to help them have a more meaningful experience. The one thing that we can do is to shift our norms in a small way. The least we can do is to stop guilting people into prioritizing others’ ability to take a photo over their own opportunity to feel in communion with a beautiful place.

The right to photo-bomb should not be misconstrued as encouragement to be an asshole. If you can easily avoid walking through someone’s photograph without disrupting your enjoyment of a place, you may as well do so.

But for the most part, it is time for a change of attitude. The next time I am rushing through the streets or visiting a special place, I will do my best to ignore all the people taking pictures. You should claim the same freedom for yourself.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply