The great nineteenth-century novelist Harold Frederic (The Damnation of Theron Ware) had a character complain “I cannot read or listen to the inflated accounts” of the role played in the Revolution by Massachusetts and Virginia “without smashing my pipe in wrath.”

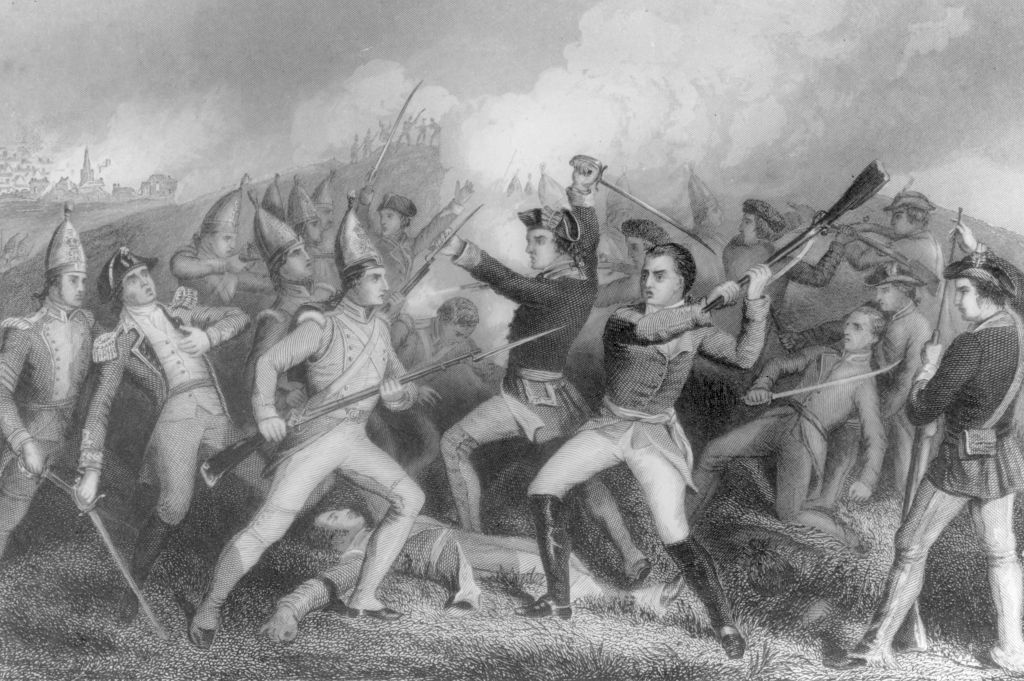

Frederic’s pipe-smasher would smoke in peaceful raptness while reading Alan Pell Crawford’s engrossing new book, This Fierce People: The Untold Story of America’s Revolutionary War in the South. While the dwindling number of Americans who care about anything that happened before last Tuesday “think of the War of Independence almost exclusively in terms of stirring stories about its beginnings — Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, Washington crossing the Delaware, the cruel winter at Valley Forge,” says the author, “most of the war took place not in the North but in the South, and that is where the most decisive battles” were fought. Those were “mainly in the Carolinas” rather than Virginia, adds Crawford, “which reminds me of the old line about North Carolina being a valley of humility between two mountains of conceit.”

My eyes usually glaze over when reading about battles, but Crawford brings his cast of characters, ranging from “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion to the alternately cavorting and cruel British officer Banastre Tarleton, to life with a beguiling blend of erudition, wit, insight and sympathy. He is the kind of historian who gets his hands dirty and shoes muddy and skin mosquito-bloodied while mucking about on battlefields and poking around in swamps. “I like to see and feel what I’m writing about,” he tells me. “Why else do it? I know one guy who bragged that he wrote his entire book just using his laptop. I don’t understand that.”

Alan Crawford is a native of Evansville, Indiana, an Ohio River town which Madonna called the American Prague. (She didn’t mean that as a compliment; the rampant hag was sore that her lodgings didn’t get MTV when she was in town filming A League of Their Own.) Yet Crawford has made a literary reputation on his fluid narratives of late eighteenth and nineteenth-century Southern history.

“I’m a romantic,” he says from his home in Richmond, Virginia. “I like ‘thin places’ and old battlefields and plantations, and Virginia has no shortage of these. And I like strange characters like [John] Randolph of Roanoke” — a central figure in Crawford’s earlier book Unwise Passions — “and Edgar Allan Poe, who grew up here.”

Crawford cuts his own profile as a Richmond character. Looking like a cross between Ashley Wilkes and an eighteenth-century European composer not unacquainted with the demimonde, he is the hollow body guitar-playing impresario of the Ham Biscuits, a five-piece jazz and blues band that he describes as “Virginia Ham meets New Orleans Gumbo.”

Is there a theme to his eclectic oeuvre?

“I’ll leave that to my many biographers to figure out,” he jokes. “This should keep literary critics and social scientists and specialists in abnormal psychology employed for many years to come.”

As for the historiography of the American Revolution, Crawford thinks we may wind up missing those braggarts from the Old Dominion and the Bay State who vexed Harold Frederic. “Virginia will probably not inflate its role in the Revolution for the foreseeable future because people who decide these things seem to regard Jefferson as something of an embarrassment. He was our governor during much of the war — and not comfortable in that role. I thought Virginia would play up its Revolutionary War herit- age since it is increasingly playing down its role in the Civil War, but I no longer see that happening. People will know less and less about our country’s history as time goes by, which is discouraging.”

Thomas Jefferson was the subject of Crawford’s perceptive and moving Twilight at Monticello, an account of the sunset years of the third president, whom the author is not about to malign in a presentist huff.

“OK, Jefferson had his ‘flaws,’” he concedes. “That is what people like to say about the great men of the past who are discovered to have been human. Who doesn’t have flaws? What critics of Jefferson seem not to understand is that he was the one American of his time who did more to transmit Enlightenment ideas of liberty and equality than anyone else, and that those are the very ideas his critics use to disparage him today. He established the standard by which he is denounced.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply