My diary has been filled with dental appointments, reflecting a truism that American dentists pray for British teeth. The tally in this past month is one root canal, three extractions and two bone grafts, which more or less equals the cost of putting one dentist’s child through a year of college. The epic began almost a year ago with a mild toothache, which my usually excellent dentist in Charleston, South Carolina, insisted needed the attention of a specialist. I rejected her advice with the confident assurance that I was getting old, the pain was mild, and it was a race between the tooth and death, a race that death would win. The tooth won. Are British teeth among the worst in the world? I have no data on the subject, but some years back I was invited to the Strawberry Hills Races in Virginia, a very social event with four steeplechases and a single flat race. It was a delightful day out, but I did think at one moment that I was back in Britain, as the crowd overwhelmingly seemed to have bad teeth and wore Barbours.

It has been a wretched year. In any usual year I manage to visit Britain twice, but we haven’t flown to London in 19 months. I should not really complain about being locked down, as I have been writing a new Sharpe adventure and writing is, anyway, a solitary vice. We spent the entire time on Cape Cod, one of America’s more civilized enclaves. Charleston, where we usually retreat to in the winter, is charming but the television adverts for firearms never cease to astonish me. Last year we were encouraged to buy a semi-automatic assault rifle for $425 and the shop would throw in a ‘lady’s handgun’ for free. We eschewed the offer, relying for our protection on an elderly Cavalier King Charles spaniel called Whiskey.

Whiskey, like many of his breed, has a heart problem which is treated by, among other drugs, Sildenafil, which is the fancy name for Viagra. He is also deaf and increasingly toothless, which I suppose reflects his solid British ancestry. None of these ailments seems to worry him. My wife complains that I am going deaf too, an assertion I reject by saying she speaks too softly, and then remind her of Coleridge’s dictum that the ideal marriage is between a deaf man and a blind woman.

Marriage is somewhat on my mind these days, because the pandemic canceled a ceremony at which I was to officiate. The bride and groom are wonderful young people, both struggling to break into the acting profession in New York, and I was looking forward to the festivities. It would have been my fourth marriage ceremony. The first wedding I conducted was in Massachusetts, where I needed a special license to declare them man and wife. Such things are not cheap and I left it to the groom to acquire the license, which he did, but mistakenly cited Chatham as the town where he was to marry instead of Harwich, next door. The mistake was not noticed until the day of the wedding, when there was no time left to correct the error, which would have resulted in an invalid marriage. The solution was to go through the whole ceremony, but before bottles were opened or cakes cut I bundled them into my car, drove them half a mile across the town line into Chatham, pulled off the road and solemnly married them with one brief sentence. ‘Your child,’ I then assured them, ‘will not be a bastard.’ The child is indeed legitimate, but the parents have since divorced.

The second wedding was in Charleston. The groom, a dear friend, is a doctor from Dublin and he was marrying the dentist who wanted to save my tooth. The marriage has survived. As has my third wedding, which was a theatrical affair, one of the grooms being the musical director of a theater. Musicians and actors flocked in from New York and the ceremony was enlivened by these talented guests on stage. It is the only wedding I’ve attended which needed a company bow at the end.

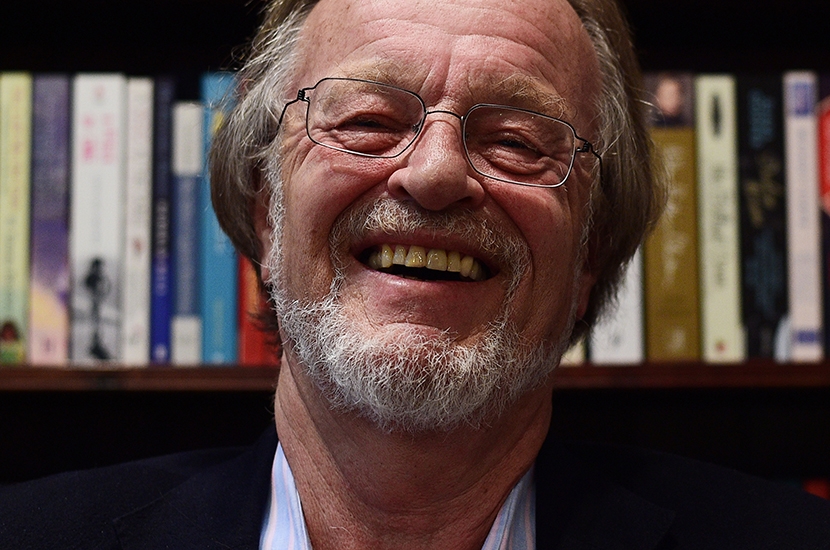

But why ask me? I accept that friendship was involved, but my conviction is that Americans assume that a British accent adds dignity to the proceedings. I hope it does, as the young couple from New York tell me they want to marry this fall, and there are whispers of a fifth couple who want a dignified accent to solemnify their vows. To obviate the need for a license, I am now a minister in a ‘recognized denomination’. I even carry a card which identifies me as the Revd Bernard Cornwell, which unlikely transformation was achieved by 10 minutes on the internet, culminating in a solemn moment when I clicked a button labeled ‘Ordain Me Now’. I just hope the accent survives my new American teeth.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.