Readers of The Spectator who keep up with the latest literary hissy fits could have predicted (perhaps with a groan) exactly what Shriver will write about this week.

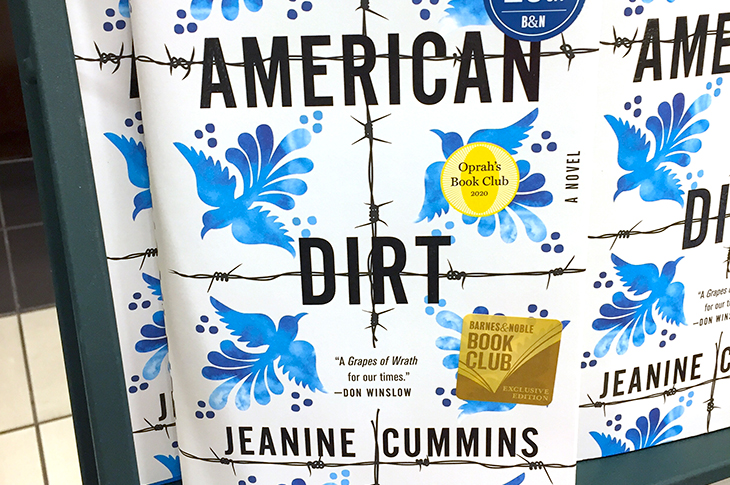

Maybe it’s hard to pity Jeanine Cummins. Her third novel, American Dirt, secured a seven-figure advance, an Oprah Book Club pick and a huge publicity campaign (waste of money; last week the Guardian alone gave the book a scale of promotion that its publisher Flatiron Books could never afford, although the paper’s worthies are sure testing that maxim about no publicity being bad). An author’s note, in which Cummins rues not being ‘browner’, suggests a faint premonition of the stir that her thriller would cause. Yet I’m betting the poor woman had no idea that she’d set off the kind of ‘stir’ that sloshes the entire contents of your coffee mug across the counter and on to your crotch.

I’ve not read this novel, and probably won’t. I’m fascinated by the issue of immigration because of its infernal political and ethical complexity. A story about the terrible travails of a Mexican woman and her son while fleeing a violent cartel and heading for the US border sounds thematically one-dimensional and, as a weird, wishy-washy New York Times review describes it, polemical. But I’d never boycott the novel because the author has the wrong skin color.

Granted, it wasn’t canny for Flatiron Books to advertise Cummins’s lone Puerto Rican grandmother by way of polishing her ‘Latinx’ credentials. (FYI, ‘Latinx’ is an artificially genderless contrivance adopted primarily by right-on white folks. From what I’ve read, ordinary Latinos seldom use it.) Better to concede: ‘Yeah, she’s white, what of it? Because we all have a right to write about whomever, whatever and wherever we like.’

The frenzied objections to this novel are two. The first regards verisimilitude. Mexican-American writers have complained about, say, the spelling of certain character names, or the fact that too many Americans visit a fictional Mexican bookstore. Sounds nitpicky.

Fair play to Cummins for spending seven years on this book, making multiple trips to Mexico and interviewing migrants at the US border. Many fiction writers working within the realistic tradition are similarly obsessive about doing their homework. Others are careless, sometimes because the point is a cracking good story and the reader doesn’t really care whether there’s a Tesco or a Sainsbury’s on the corner of the Old Kent Road and Humphrey Street. I tend to err on the homework side myself, because for an informed reader inaccurate details can jar and create distrust. But this is a matter of craft. Small errors of authenticity are technical flaws, and unless they’re on virtually every page this criticism is petty. Inaccuracies are not insults. If anything, factual mistakes tend to foster a sense of reader superiority.

Then there’s the separate question of the author’s moral right to her material, and that is, as usual, the central controversy here. Plenty of Cummins’s detractors would decry her novel even if they couldn’t catch out a single Mexican character putting chipotle rather than pasilla negro chillies in a chicken mole. Cummins is white, so the subject of Mexican migration doesn’t belong to her.

As ever, I’m loath to invoke ‘cultural appropriation’, a concept to which I am anything but attached, but which seems to have attached itself to me. The expression slyly assumes the conclusion; call this ostensible theft ‘cultural appreciation’ and at least your opponents have to make an argument.

Never mind appropriation; let’s look at ‘culture’. Amorphously, culture is the sum total of all you were socially born into: language, convention, costume, music, belief…there’s nary an aspect of living alongside other people that doesn’t belong under this umbrella. Culture is what for the most part you did not create, and so can’t take much credit (or blame) for.

It stands to reason that what you can neither precisely define nor claim to have made you also cannot own, much less exclusively sell (much of the aggro over American Dirt seems fed by commercial envy). In kind, you can’t own stories. You can’t patent topics and classes of character. Fiction writers rightly avail themselves of an infinite array of toys in the global playpen. Another novelist might credibly tell the story of my own life better than I could.

True, there are subjects from which I shy. I’m unlikely to write a novel that’s all about Indonesians. Starting from ignorance, I’m too lazy to do the research, and I’ve never got an idea for a novel set in Java. I only embark on books that I hope will make a unique contribution. So I’ve never written about the Holocaust, either — not because it doesn’t ‘belong’ to me, but because I couldn’t improve on Elie Wiesel. As we’ve recently been reminded, the Holocaust indicts not one nation but a whole species. The Holocaust belongs, alas, to all humanity. I wish it didn’t. I don’t want it.

Latinos are free to write their own novels about migration, for American literature is awash in inspiring tales about the newcomer experience authored by immigrants. Readers are free to post mean reviews of American Dirt on goodreads.com. In turn, Cummins should be free to pour out her liberal heart on the page, and Flatiron free to make pots of money from all this grief.

Before last week, the Cummins news story was broadly heartening. Flatiron was standing by her novel; bookstores weren’t pulling it from their shelves; Oprah hadn’t withdrawn her endorsement. But then the publisher issued a fatal apology — for promoting the novel as having ‘defined the migrant experience’ (publicity materials always make ridiculously grandiose claims for novels — including mine — which are always ‘defining a generation’ or some such) and for the centerpiece at their booksellers’ dinner, of all things. Multiple bookstores now won’t sell the novel. The author’s nationwide tour has been canceled over ‘security fears’.

This is the first major mainstream release to be hit by this ‘appropriation’ folderol. I keep waiting for the nonsense to peak and subside, but it only gets worse.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.