The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson is a must-see show. Originating as an exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the Met’s show is certainly the museum’s largest solo exhibition of an African-American artist’s work in recent memory, perhaps ever. It’s definitely the biggest-ever showing of Wilson’s work, but the Met is not patting itself on the back on these points. The show is a tribute to a fine artist of boundless talent, a painter of deeply felt and expertly rendered works, even if it will not rewrite any narratives of art history.

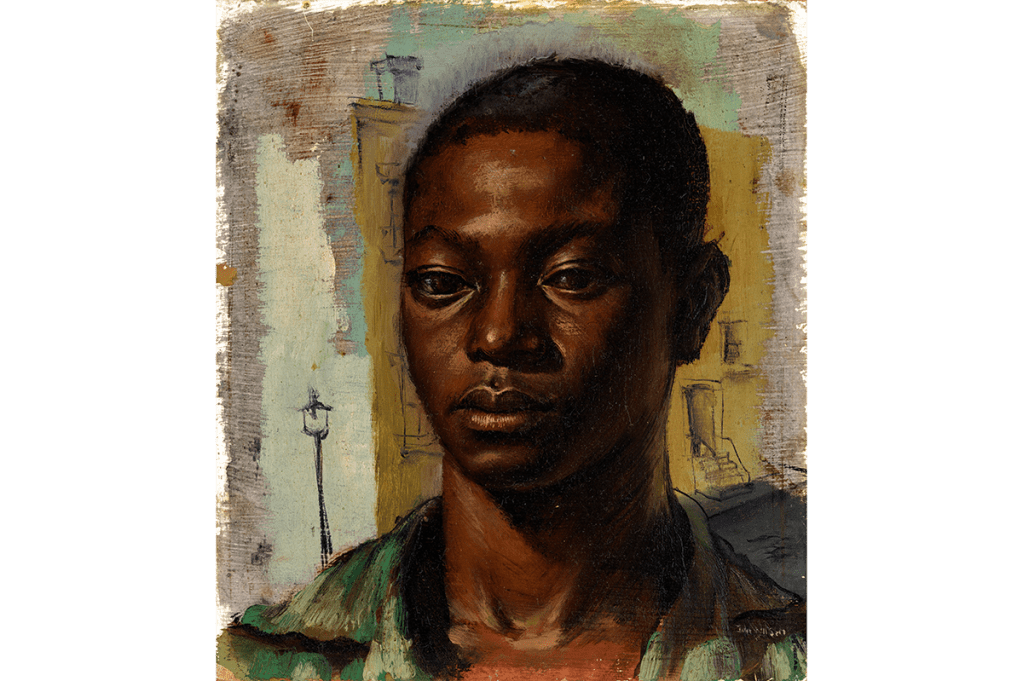

Wilson (1922-2015) was an African-American artist of Guyanese descent who had a long and many-chaptered career. He found success early, painting his preternaturally excellent portrait “My Brother” when he was only 20 years old. He was exhibiting at the Museum of Modern Art by the time he was 27. Though mostly associated with Boston – he taught at Boston University for 20 years – he also studied in Paris with Fernand Léger and made murals with David Alfaro Siqueiros in Mexico City in the 1950s before teaching in New York’s public schools in the 1960s. His talent shines through in all these chapters.

‘The Young Americans’ preserves the cool, welcoming, artsy interracial scene of the Wilson home in the 1970s

I am tempted to advocate for appreciating Wilson’s art without getting too much into the exhibition’s sociopolitical framing about his reception and his choice for representation over abstraction. There is an undercurrent of tension between the curators’ insistence upon saying “Look at all his success!” on the one hand, and “He’s so underappreciated!” on the other. His preference for representation has long been pinned as the reason for his underappreciation, but to the extent he is less well-known than some of his contemporaries, it’s not because he set aside abstraction.

Rather, Wilson never really invented a sustained, recognizable style or repurposed an existing form drastically enough to make one instantly say, “That’s a John Wilson portrait” in the way one can immediately recognize, for example, a Romare Bearden collage. Plenty of African-American abstractionists remain underappreciated too – Norman Lewis and Ed Clark also deserve retrospectives.

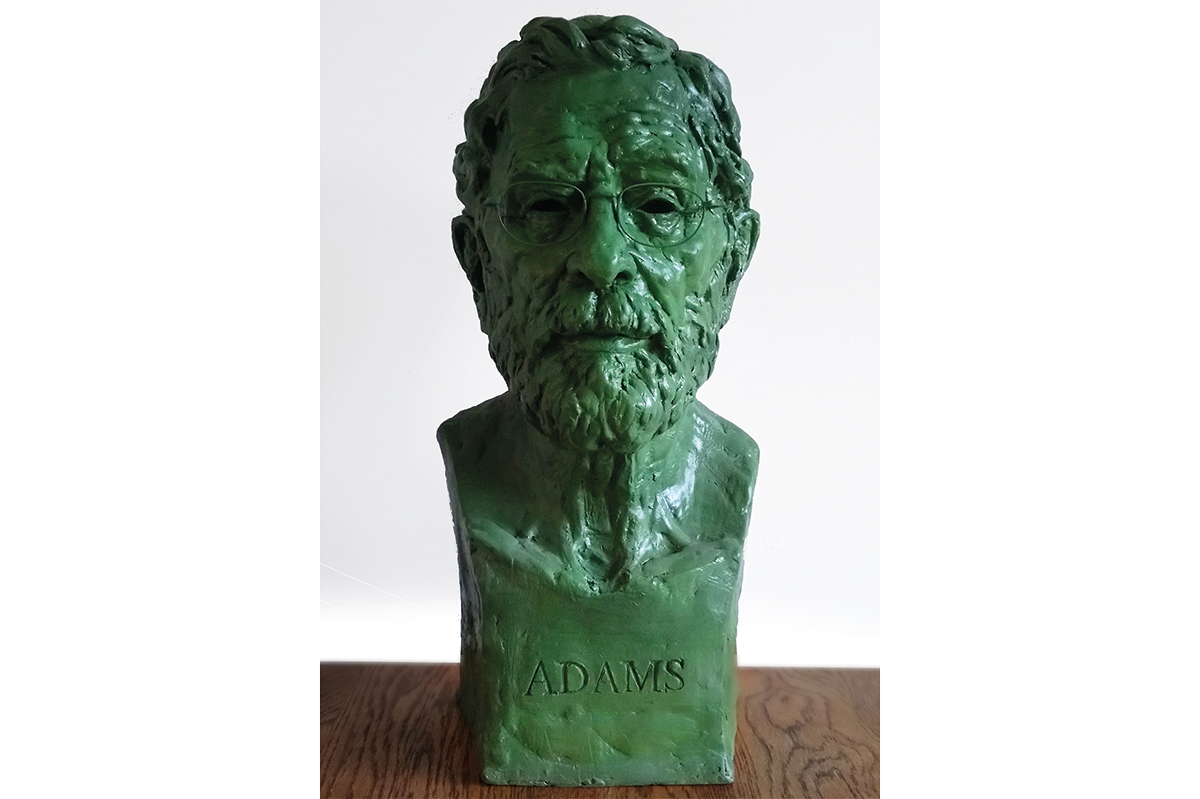

Wilson was not a mimic exactly, but he did have a knack for echo and homage. Of his self-portraits, I overheard someone in the preview say, “It’s like Cindy Sherman before Cindy Sherman!” For sure, but they’re also like Rembrandt after Rembrandt. Wilson’s “Street Children” (1973) suggests a look obtained by the Swiss-French painter Félix Vallotton; the striking “Streetcar Scene” (1945) alludes to Honoré Daumier. Other works bring to mind Stuart Davis and Léger. “Eternal Presence” (1985) suggests Olmec and Buddhist influence – Wilson was known to be interested in both.

He was keen to provide respectable representation of African-American life and he had his sights on interracial harmony. “Deliver Us from Evil” (1943) suggests the need for black-Jewish solidarity during World War Two. Wilson’s wife, Julia, née Kowitch, was Jewish.

His interest in other groups led to “The Young Americans” (1974), one of the most memorable works in the exhibition, which was very much of its time yet feels alive and contemporary today. A series of vibrant portraits in crayon and charcoal, “The Young Americans” preserves the cool, welcoming, artsy interracial scene of the Wilson home in Brookline, Massachusetts, in the 1970s.

As Shelley R. Langdale of the National Gallery of Art writes in the catalogue, the house was “the favorite hangout of their teenage children and their friends of all races.” This harmony is at odds with the more lachrymose portraits of those years in Boston evident in such books as J. Anthony Lukas’s Pulitzer-winning book, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (1985).

Wilson envisioned “The Young Americans” as a major mural but could not obtain the funding. This is regrettable. It is one of many hints of what might have been, as are his intense illustrations in “The Richard Wright Suite” (made for Wright’s Down by the Riverside). An enterprising publisher might have transformed Wilson into the successor to Rockwell Kent. But while the contours of career frustrations can be glimpsed, what is on display is testimony to significant talent and integrity.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 13, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply