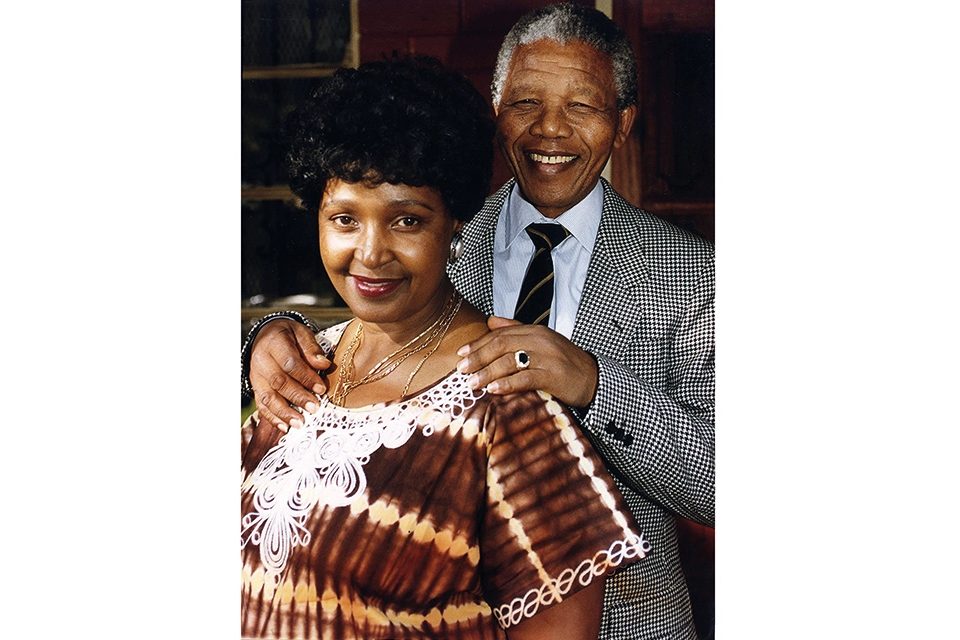

Apartheid South Africa created many heroes and villains, and in the heat of battle for the soul of that country it was sometimes difficult to tell which was which. For decades, Nelson Mandela represented righteous liberation for a society enchained by the grim political philosophy of apartheid. Throughout most of this time, his wife Winnie embodied fearless defiance and radical resistance to the system, a charismatic beauty who howled with rage: according to Lord Hain, “a quasi-revolutionary to Mandela’s reformism.”

A complex Shakespearian tale unfolds of two charismatic figures thrown together by apartheid

Today, as South Africa lurches from one crisis to the next, the legacy of the Mandelas is up for grabs. While history will mark Winnie down as an accessory to murder, a psychopath who oversaw the kidnap and torture of young men, an embezzler, an unblushing and unprincipled liar, today’s young black radicals of Julius Malema’s Economic Freedom Forum Party hold her in the highest regard as the true voice of liberation. Equally, historians argue that Nelson’s calm pragmatism on his release from prison saved the country from descending into civil war. But as his ruling ANC Party stumbles through corruption scandals and the chronic mismanagement of the economy, his legacy becomes increasingly tarnished.

So, although Jonny Steinberg’s detailed and beautifully written biography of the couple is billed as a portrait of a marriage, it is much more than that. By tracing the lives of these two charismatic individuals — one a social worker, the other a Thembu prince — from the pre-apartheid days through to their inevitably sad ending, he is telling the bigger story: of a country in transition and at war with its own people. As a South African and Oxford academic, Steinberg fully understands the nuances and double entendres that course through the nation’s body politic.

I had a brief experience of it in the late 1980s. When I interviewed Winnie for Vanity Fair at the ANC headquarters in Johannesburg, after spending several months investigating the events surrounding her notorious Mandela United Football Club, I have to admit I was seduced by her charm. Then in her fifties, she was warm, witty, empathetic and radiantly beautiful. It was difficult to reconcile the person sitting in front of me with the picture people in Soweto had been painting of a violent devil-woman drenched in blood.

We talked at length about what everyone called “the struggle” — the years of suffering she had endured at the hands of the white Nationalist government. Then I said I had to ask her about the allegations surrounding the recent murder of fourteen-year-old Stompie Moeketsi Seipei. She immediately leapt to her feet, kissed me fully on the lips, smiled disarmingly and swept out of the room, declaring, almost as an afterthought: “I deny all the allegations with the contempt they deserve.” At the time it seemed a surreal encounter. With hindsight it was just another day in the life.

What unfolds in Steinberg’s book is a complex Shakespearian tale of two charismatic figures who were thrown together in the dark days of apartheid. The marriage between the world’s most famous political prisoner and the liberation movement’s first lady lasted thirty-four years, most of it conducted in parallel worlds. Within twenty months of their wedding in 1958, the couple had had two daughters, Nelson had been arrested for treason and gone underground, then been rearrested, tried and imprisoned for twenty-seven years. By the time he re-emerged in February 1990 the world — and Winnie — had changed.

Over those decades Winnie metamorphosed from “shy country girl,” as she described herself to me, to a political firebrand and international celebrity, to street criminal and enemy of her own people, to populist politician without portfolio. In fact, throughout all of this, those who knew her well thought she remained pretty much the same person. As the South African political commentator Allister Sparks said: “The essential qualities — her imperiousness, her willfulness, the combative and survivalist spirit — that helped her get through the hard years also brought about her downfall.”

As with all great tragic narratives, it is in Steinberg’s final chapters that we come fully to understand the scale of this story. Having been divorced and estranged from Winnie for fifteen years, and remarried to the saintly Graça Machel, Nelson, who was now suffering from dementia, called for Winnie on his deathbed. It was she who was at his side, comforting him in his last days.

Five years later Winnie died, and her funeral, at Orlando Stadium, just a mile from the couple’s former marital home, became an ideological battleground, where Winnie was generally revered as an unbending revolutionary force and Nelson dismissed as “an old gentleman from the past.”

Suddenly, the man who had been largely credited with the peaceful transition from the old to the new South Africa was regarded as a collaborator, an Uncle Tom. Steinberg writes:

Most profoundly, when young people looked for a usable past, they increasingly turned their gaze from Nelson, searching for figures who had been suppressed, figures like Steve Biko, Robert Sobukwe and, indeed, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.