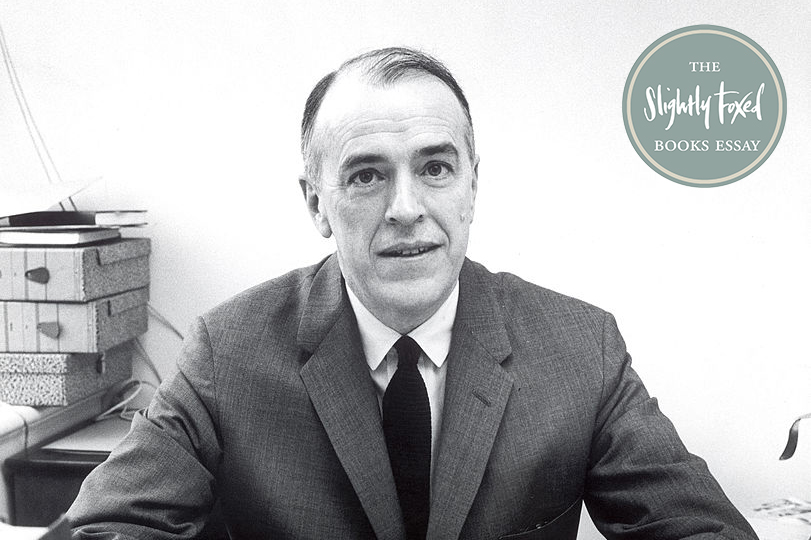

A curious thing: the New York literary world is smaller than the London literary world. It also has a strange feeling of being more old-fashioned. I was edited there by the legendary Joe Fox. I don’t think he liked me, but we would have dinner at a hotel restaurant, the last place where he could smoke in New York, and talk about great writers, including William Maxwell. Joe Fox died at his desk in Random House behind a huge pile of copies of the New York Times, cigarette on his lips.

William Maxwell himself was one of this relatively small but influential group of New York literary figures. Because of his very long life and his great influence as literary editor of the New Yorker, he knew almost every writer who passed through the city. When Maxwell died two years ago, at the age of 91, John Updike wrote in his tribute to him in the New Yorker:

‘He accepted with his customary grace and humor his own contrary fate of living on and on . . . He was himself so large- minded, so selflessly in love with the best the world could offer, that he enlarged and relaxed those who knew him. His was a rare, brave spirit, early annealed in terrible loss. He had a gift for affection, and another – or was it the same gift? – for paying attention. With both he graced this magazine.’

Maxwell’s great loss, to which Updike refers, was the death of his mother when he was a boy out in Illinois during the ’flu epidemic of 1918 (in which my own grandmother died, leaving my mother bereft). This loss, and the consequent vivid, nostalgic memory of an idyllic childhood destroyed, was the subject of his own literary endeavors and provided him with three-quarters of his literary material. To read Maxwell now is to be taken back into a time and place lost forever. It is an extraordinary and wonderfully surprising experience: here is an American provincial world presented in miniature and in exquisite detail, as though the death of his mother froze Maxwell’s sensory memory in one place and in one time.

In almost all of Maxwell’s novels the relationship between Maxwell and his older, more vigorous brother is replicated. Maxwell’s brother lost a leg in an accident, as have all the elder brothers in his fiction. Never, to my knowledge, have such particular incidents been used so explicitly and repeatedly. Maxwell’s net was not cast wide.

The pictures on Maxwell’s book jackets reveal a very good-looking man, who would have passed easily as one of Gatsby’s sports. In the 1930s when he came to New York from Harvard, he suffered badly from his sense of loss and he went into analysis for months. He even rewrote the ending of an early story under the analyst’s influence. But those who knew him did not notice his private anguish: they found him always calm, self-possessed and courteous, and with a remarkable sympathy for the writers he edited. Only John Cheever demurred, saying that he was power-mad and used kindness as a form of control. But then Updike, who had believed Cheever liked him, found that Cheever had written very dismissively of him in private. In some ways Cheever, a heavy drinker and womanizer, was the antithesis of Maxwell, who led a very contained and narrowly proscribed life. It was as though his early trauma and his own sexual feelings had to be kept in the bottle.

So Updike’s use of the word ‘annealed’ seems to me to be absolutely right. For four decades Maxwell went on, patiently editing, confining himself within a tight circle, ignoring the outside world, unimpressed or uninterested in radical or avant-garde work, and from time to time producing his own exquisite stories. But the most extraordinary fact about him is that what happened to him at the age of 10 seems to have provided him with more than enough experience for his fiction.

His last novel, published in 1980, is So Long, See You Tomorrow. If you are interested in Maxwell, this is possibly the best one to start with. As usual we are back in Illinois. It opens with the murder of a tenant farmer in a place and at a time when murder was very rare, and it shows how the events surrounding the murder affect a small boy – Maxwell’s young self again, now 13 and complete with older brother who has lost a leg and mother taken away by ’flu. Maxwell has his hero say of his mother:

‘I clung to the idea that if things remained exactly the way they were, if we were careful not to take a step in any direction from the place where we were now, we would somehow get back to the way it was before she died. I knew that this was not a rational belief, but the alternative – that when people die they are really gone and I would never see her again – was more than I could manage then or for a long time afterward.’

Against this background and the arrival of a stepmother, as happened to Maxwell, the hero meets a strange boy, Cletus Smith. When it becomes clear that Cletus’s father killed the tenant farmer, the friendship between the two lonely boys ends, and this betrayal still troubles the narrator fifty years later.

What follows is absolutely compelling: we become intimately and absolutely drawn into this small world and the very banal domestic tragedies that led to the betrayal. The richness is in the detail: the grammar of the local newspaper editor, the murderer’s funeral, the look of the buildings, in fact the sheer texture of this lost world recalled decades later against a background of the hero’s own emotions. And this is, for those who love Maxwell, his uniqueness — a vividly, almost obsessively, remembered childhood; gentle, often amusing ironies; and a deep sense of loss, all recreated with unobtrusive skill. Maxwell couldn’t be further from the world of New York writers like Mailer and Baldwin, which he shared. In some ways he reminds me of Jane Austen, with just a touch of Raymond Carver.

As a young man he was deeply influenced by the English writer Sylvia Townsend Warner, unknown to me, but a contributor to the New Yorker and a substantial novelist and poet. Maxwell said, ‘I think what you are infinitely charmed by, you can’t help unconsciously imitating.’ I concur. A delightful collection of their forty-year correspondence is now available under the title The Element of Lavishness.

Many people believe that Maxwell has been unfairly disregarded as a writer, but the truth is that his novel They Came Like Swallows, which was published in the same year as The Great Gatsby, has never been out of print, and Maxwell won awards and recognition while Scott Fitzgerald was for many years completely ignored. The magic of Maxwell is in the unexpected, rather European quality of his writing. It is true that so far he has not gained any very wide readership, but I detect signs in Britain that this is changing. He seems to have become the sort of writer serious readers want to know about.

This article was originally published in Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. Eclectic, elegant and entertaining, Slightly Foxed introduces readers all over the world to good books from the past and present.