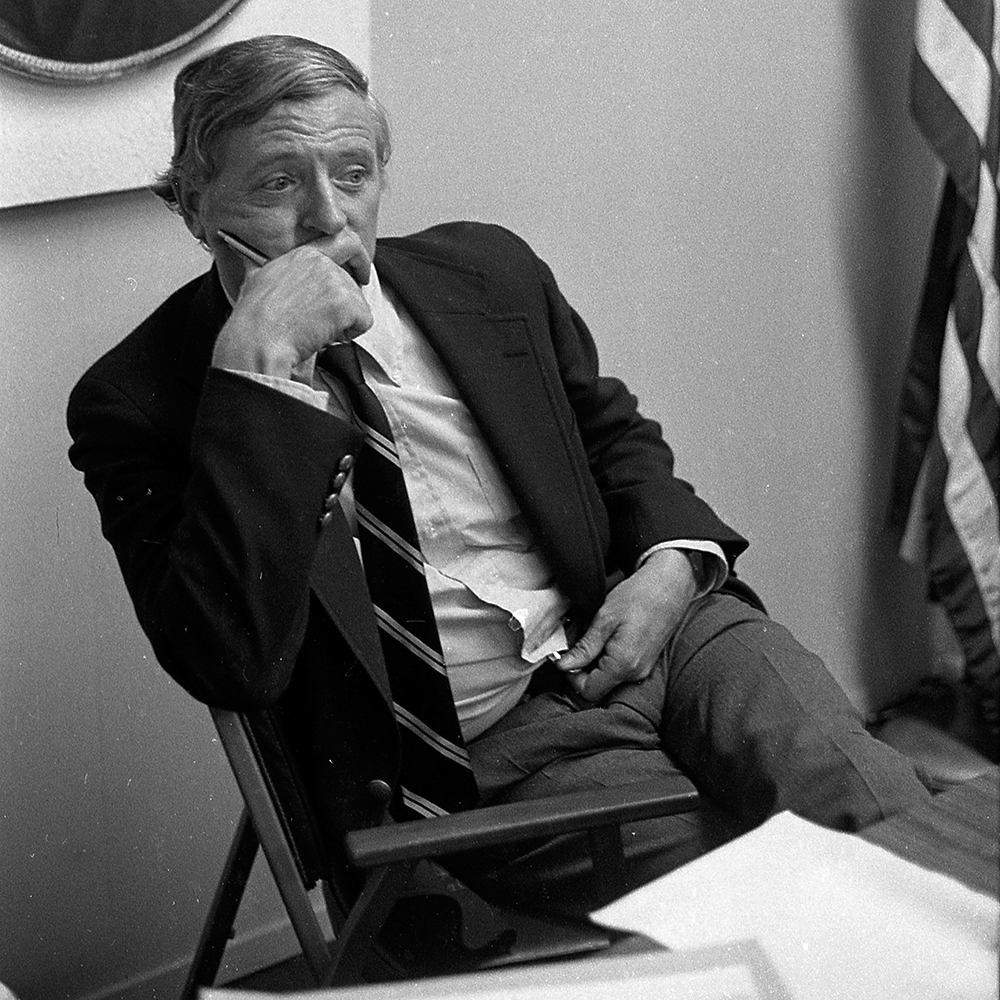

What more can be said of the American conservative commentator, novelist, musician, sailor, talk-show host and tireless public intellectual William F. Buckley Jr. (1925-2008), that he or his previous biographers haven’t already said or written? After all, this is an individual who in 1983 wrote a 90,000-word book, called Overdrive, covering the events of a single week of his life. Plenty more, it turns out, as Sam Tanenhaus proves in his thousand-page biography Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America.

Buckley was blessed with a voice that sounded like he let it marinate in a cask of port between appearances

Buckley was 58 when he wrote Overdrive, and kept to a schedule that would have taxed the energy of a man half his age. Somewhere amid the blur of television appearances, newspaper columns and placing phone calls to his old friend in the White House, Ronald Reagan, Buckley gives the answer to the secret of his productivity. “Deadlines,” he writes. “I have deadlines for everything. I find them liberating.” Expounding on the theme in a television interview to promote the book, Buckley added: “I had three deadlines this weekend. And because they simply had to be done, they were done. The people I pity are not the people who have deadlines. They’re the people who don’t have deadlines.”

Somehow that sums the man up. Buckley was a prodigious speaker and writer, blessed with a voice that always sounded like he took it out and let it marinate in a cask of port in between appearances. He had an extensive, Latinate vocabulary. One of his editors at Doubleday remarked that Buckley’s use of language elicited “both exasperation and admiration.”

Though far from a political kindred spirit, even Norman Mailer recognized a fellow raconteur and master of the perfectly turned multisyllabic phrase when he saw one. “You can’t stay mad at a guy who’s witty, spontaneous and likes good liquor,” Mailer said.

Bill, as he was universally known, was the sixth of ten children born to an oil-developer father and a polyglot Swiss-German mother and learned French and Spanish from nannies before attending schools in Paris and London. He served in the US Army from 1944 to 1946, and then fired his first palpable shot in the culture wars while acting as “chairman,” or chief editorial writer, of the daily campus newspaper at Yale University. There would be “no squeamishness about editorial subject matter,” a 23-year-old Buckley wrote in his first opinion piece. The right, he added, needed “a brigade of intellectuals who must preach American principles and advance natural rights and divine sanction.” Lest that not already put his readers on notice of an agile contrarian mind at work, Buckley went on to announce that the innocuous series of articles published by his predecessor, under the headline “What Makes a Course Good?” would henceforth go by the amended title of “What Makes a Course Bad?”

Not content with a general critique of the Yale curriculum, Buckley zeroed in on a particular faculty member, a widely popular sociology professor with a specialty in the indigenous cultures of Southeast Asia named Raymond Kennedy. Kennedy possessed a “bawdy, slapstick humor,” Buckley allowed. But the professor’s classroom arguments against Christianity were too much. Yale, Buckley pointed out, had been founded by ministers specifically to educate the future leaders of a Christian nation. “Jungle Jim,” as he called Kennedy, was “without doubt, very funny – but then so are Bob Hope and Bennett Cerf.” In mocking Kennedy, the undergraduate seemed to have prefigured one of the truths of our modern political discourse, namely that personal attack, often in terms far less articulate than his own, would increasingly come to seem just as reasonable a form of public criticism as any other kind.

Never content to end a fight until his opponent was thoroughly crushed, Buckley went on to write a book about his experiences at Yale – and the result was a scathing indictment of his alma mater, God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom.” It was as though the author had brought a bazooka to an academic arena where polite young men traditionally resolved their differences in a fencing match. By the time of his 30th birthday, Buckley had already become a progenitor, and perhaps the best-known proponent, of a certain kind of robust American conservatism.

His ambitions in that direction weren’t limited to the abstract. At around the time of God and Man’s publication, Buckley also began a parallel career as an undercover CIA agent in Mexico City, reporting back on pro-communist activity. His station chief there was none other than E. Howard Hunt, who 20 years later helped plot the Watergate burglary and other clandestine operations for the Nixon administration.

The success of Buckley’s first book would serve to cut short his time in the looking-glass world of espionage, and in 1954 he followed his Yale demolition job with a stout defense of the embattled Senator Joseph McCarthy, the Wisconsin Republican who was leading a high-profile campaign against communists in American life.

This book, apparently 20 years in the making, shows a rare familiaritywith its subject and his times

In 1955, recognizing a gap in conservative journalism, Buckley (then 29) launched and edited the then-weekly National Review, which he clearly saw as the new voice of the American right. The magazine, he wrote in its founding statement, “stands athwart history, yelling ‘Stop’ at a time when no other is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it.” Many more articles and books followed, as did the hour-long television show Firing Line from 1966 onward. Buckley hosted 1,054 episodes over 33 years, making it the longest-running such public affairs show in TV history. Buckley’s idiosyncratic voice and bared teeth, along with an almost horizontal slouch that combined an air of patrician languor with that of a coiled snake, came to be known to millions of viewers who would never normally go near the minefield of intellectual public debate.

Buckley combined all this with sub-careers as a harpsichordist, trans-oceanic sailor, prizewinning novelist and good-natured loser in a New York mayoral race where he won a respectable 13.4 percent of the vote and, as even his opponents allowed, thrilled with his oratory.

Toward the end of his life, his platform technique managed to combine the sophistication of a pedigree kennel-club champion with the more combative approach of a rabid pit bull attaching itself to an opponent’s windpipe. “Now listen you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I’ll sock you in your goddamned face, and you’ll stay plastered,” Buckley famously told Gore Vidal during their televised debate at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, thus somewhat abandoning his reputation for high-minded rhetoric. Both men later sued each other for libel.

Lest it not already be clear, Buckley was not a man who could reasonably be called a martyr to false modesty. “I am, I fully grant, a phenomenon,” he allowed in a 1986 article entitled “On Writing Speedily.” “But not because of any haste in composition. I asked myself the other day, ‘Who else, on so many issues, has been so right so much of the time?’ I couldn’t think of anyone.”

One area in which Tanenhaus feels his subject may not always have been in the right was that of race. In 1957, Buckley wrote a National Review editorial entitled “Why the South Must Prevail,” in which he declared white people to be “for the time being, the most advanced” of the races and, as such, the most suited to govern.

Lesser biographers than Tanenhaus, a former editor of the New York Times Book Review, have seen fit to omit the critical words “for the time being” from the notorious quote. In 2004, asked whether he had ever taken a position he now regretted, Buckley answered: “Yes. I once believed we could evolve our way up from Jim Crow. I was wrong: federal intervention was necessary.” Or put another way: “It’s one thing to take the position that the government has not the power to compel integration. It is another to take the position that Negroes be compelled to support a legally constructed monopoly,” he wrote.

In later years, Buckley was among the first public figures to call for the creation of a national public holiday in Martin Luther King Jr.’s honor, as well as for a memorial to him on the National Mall.

Clearly, then, it’s best to look at Buckley in full to get a true picture of his views on civil rights, as on so many other issues. Tanenhaus succeeds in this brilliantly well. He not only knew Buckley personally, but has had unfettered access to his private papers and absorbed an enormous amount of esoteric literature that informs the story. This exhaustive, prodigiously researched book familiarizes us not only with Buckley’s sometimes incendiary public persona, but also his relationships with friends and family – among them his novelist son Christopher – his various aches and pains and his travels.

Tanenhaus treats us to an account of Buckley’s youthful adventures in the CIA that stands comparison with the best John le Carré spy fiction, if one not untouched by comedy. If there’s a criticism to be offered of the lengthy production as a whole, it’s perhaps that there’s sometimes simply too much detail, with certain sections relying heavily on descriptions of the subject’s everyday life that hang like an artist’s drop cloth over the corner of an otherwise spectacularly vivid painting. Aside from this minor weakness, Tanenhaus is to be congratulated for his achievement. This book, apparently 20 years in the making, is the product of immense learning and shows a rare familiarity with its subject and his times. The author moves me to bestow a reviewer’s cliché I long ago vowed never to use, except in cases of extreme unction: he has surely written the definitive biography.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply