I’ll be upfront: I’m skeptical of the trans movement. Not the individuals within it, but the broader cultural shift that prioritizes feelings over facts and subjectivity over objective reality. Yet, despite my reservations, I have deep empathy for those grappling with identity confusion — an experience that must be profoundly disorienting. My concern is that we’re accelerating this confusion by feeding a culture obsessed with validation.

So, when I sat down to watch Will & Harper, I hoped, perhaps naively, that this film might grapple with these, my own very real questions, in a meaningful way. It doesn’t. What I found instead was a film that falls short as cinema and even shorter as a piece of prop art.

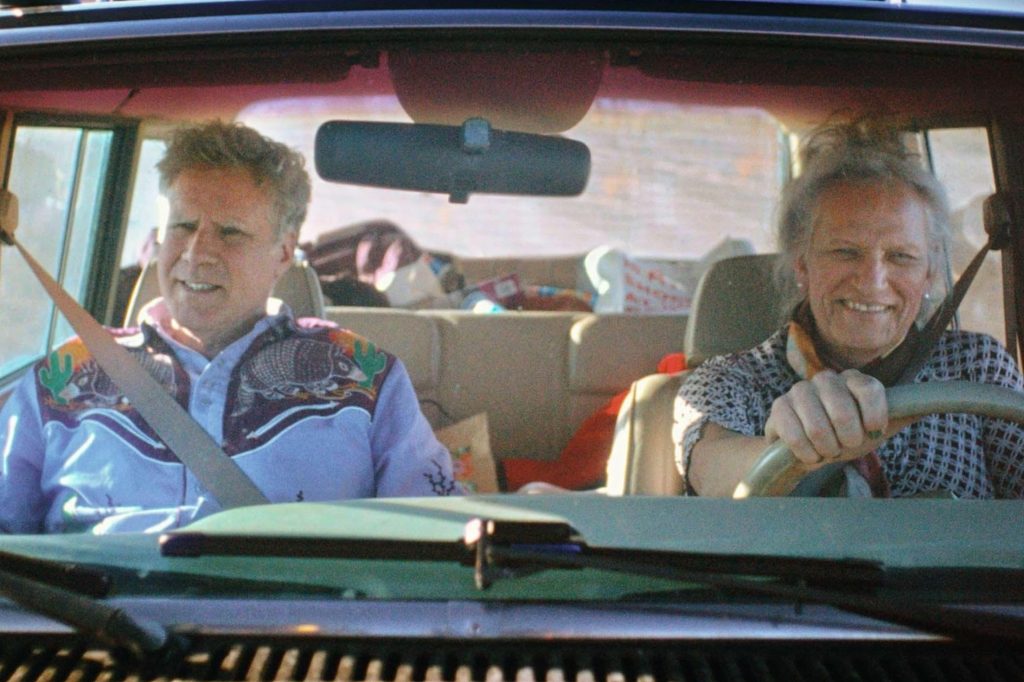

The film follows Harper, who embarks on a cross-country trip with Will Ferrell — an old friend and comedic powerhouse — to reconnect after Harper’s transition from male to female. Harper, previously known as Andrew Steele, was a writer at Saturday Night Live during Ferrell’s tenure there. It’s a fact that, to any objective watcher of this film, seems impossible to imagine. Harper in his older age is bitter, awkward and rarely funnier than your average soccer dad.

From the outset, it’s clear this journey isn’t really about exploring the contours of their evolving friendship, but about Harper’s desire to be seen, recognized and, frankly, validated. It’s not the kind of validation that comes from understanding or mutual respect, but from a self-obsession that insists the world bend to your perception, your identity, your truth.

Take, for instance, the breakfast scene. Harper and Will Ferrell’s character, ever the delightful and earnest companion, sit down at a diner. A kindly waitress misgenders Harper, apologizes, and moves on. Yet Harper is visibly shaken, as if the entire room is scrutinizing her. Ferrell tries to smooth things over, but the moment is emblematic of Harper’s larger issue: she’s constantly demanding the world recognize her, yet never offers empathy in return. It’s exhausting to watch.

Then there’s the biker bar scene, where Harper walks into what should be a tense situation — Confederate flags on the wall, leather-clad patrons everywhere. But the tension never arrives. The bikers, like everyone else in the film, accept Harper without much fuss. And yet, even with that acceptance, Harper remains unsatisfied, demanding more from a world that has already bent to her will.

It is in these moments that Will & Harper reveals its most troubling flaw: it offers no answers to the tough questions. Hell, it doesn’t even ask them. The film gestures toward the challenges of transition, the complexities of identity, but never confronts them head-on. Harper’s journey isn’t one of self-discovery, but of endless self-obsession.

This brings me to Will Ferrell. His performance is, predictably, delightful — he brings his usual warmth, humor and sincerity. Throughout the film, Ferrell is the portrait of a great friend: steadfast, kind and endlessly patient. In media appearances surrounding the film, Harper insists that through the journey “Will transitioned too.” But did Harper? Did Harper evolve in any way? Did she learn to be a better friend, less cynical, more open-minded or empathic? Or is that only a demand we place on the rest of us?

Ferrell’s unwavering support seems to fall into a chasm of one-way emotional labor. What makes Will & Harper so disheartening is that it unintentionally highlights a larger issue — Harper’s focus on himself leaves little room for genuine connection, which the film completely misses. You feel for Harper’s pain, but you end up feeling more for Will, the loving, thoughtful friend who, despite all his efforts, receives little in return. Instead of exploring the mutuality of friendship and the growth both characters could experience, the film becomes a one-sided exercise in validation that lacks depth or resolution.

In the end, Will & Harper offers little more than a shallow reflection of a much deeper cultural problem: a relentless demand for empathy, with none given in return.

Leave a Reply