For those of us who have long loved (or hated) Paradise Lost, this is one of those rare and refreshing books that invites us to compare our feelings with other committed readers over the centuries. The poem may well be the only major work in the western canon that nobody can avoid for long — even if it comes down to making a decision not to read it at all, or just to give up trying.

Orlando Reade argues that it may also be the most “revolutionary” text commonly available in modern classrooms — written by a man who, in his time, took extreme positions on everything from divorce (he was all for it) and whether kings have a divine right to keep their heads (they don’t). John Milton read widely and lived during the most conflict-driven period of British history. His longest poem — possibly the greatest poetic work ever composed — wrestles with issues he’d previously discussed in a series of widely read polemical pamphlets. For notwithstanding its lyrical and dramatic beauties (the battles between heaven and hell outblaze those of any modern fantasy trilogy), Paradise Lost is mostly about revolution — how much can individuals revolt against God, father, church and king without bringing all the heavens down upon their heads.

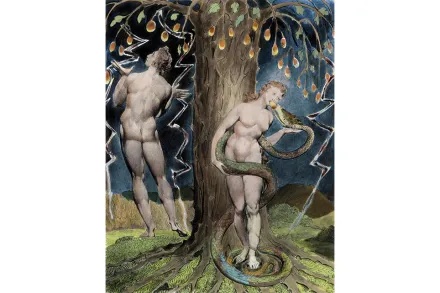

Some of Reade’s best pages concern those Romantic Age poets who moved Milton away from theological discussions about justifying the ways of God to men and into the boiling late 18th-century world of cultural politics. First and foremost was William Blake, who a friend reportedly found in his summer house “acting out” scenes from pre-lapsarian Eden, naked as a jaybird with his equally naked wife Catherine. (This was about the same time Londoners decided not to drop by one another’s homes without prior warning.) Blake went on to write and illustrate his own epic poem, Milton, in which the heaven-translated poet journeys back to London, inserts himself into Blake’s foot and engages in mystical conflicts with various celestial forces. More importantly, Blake was the first significant figure to admit to finding Milton’s upstart Satan a lot more interesting than his relatively wooden God, largely because, he claimed, Milton “was a true poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”

This would come to be a common debate over the next couple of centuries: whether to join the poetic cause of God against men or of Satan against God. For while Milton supported revolt against aristocrats and clergy who falsely adorned themselves in God-like finery, Satan’s rages against “the Tyranny of Heav’n” sounded sympathetic to most dissenters — especially after the monarchy was reinstated in 1660. During the French revolution, a young and still radical Wordsworth went to witness events first-hand in France; but as he grew wary of the guillotine-happy revolutionaries, he started internalizing Milton’s cosmic/political conflicts. The Prelude, Wordsworth’s autobiographical epic, charts how those primal Satanic conflicts worked themselves out through the “growth of the poet’s mind.”

Thus the readings and misreadings proliferated: from the early American proponents of revolution, such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, through the slave memoirs of Olaudah Equiano, right up to the 20th-century’s Malcolm X, who (like many radicals) read Paradise Lost while in prison. He found that it shared affinities with the thoughts of his religious leader (and eventual nemesis) Elijah Muhammad.

Reade’s descriptions of these wildly various readers are lively and interesting, but his efforts to connect Milton with significant names sometimes lack substantive proof — for instance with Philip K. Dick, the beat poet Michael McClure, and even the Hell’s Angels. He spends several pages recounting the student-teacher affair between Hannah Arendt and the soon-to-be Nazi education minister Martin Heidegger for no other reason than to note that Arendt, in The Human Condition, briefly refers to a note by Marx on the “labor” involved in Milton’s poetry.

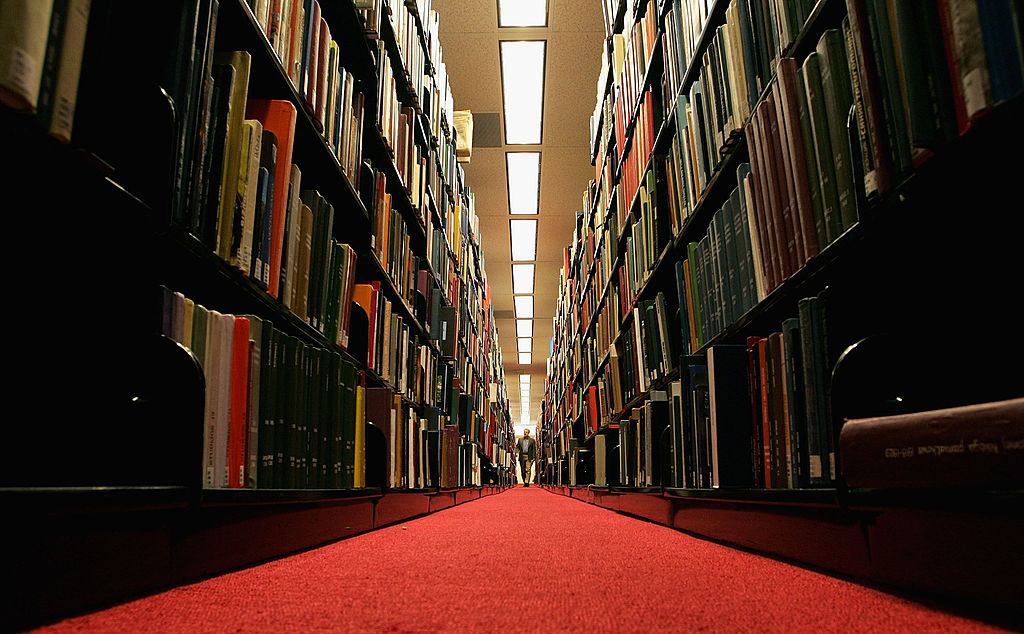

What in Me is Dark starts off with a lovely premise — the author’s experiences of teaching Paradise Lost to the inmates of a youth correctional facility in America. Reade memorably describes one of those rare, unexpected pleasures that teachers, if they’re lucky, encounter a few times in their careers: the moment when their pupils stop taking notes long enough to read (and misread) things quite beautifully by themselves:

The students… weren’t reading in an abstract, academic way, they were reading in the context of their whole lives, as something that might help to explain why we had ended up where we were, and this was why they couldn’t relinquish the idea that poetry had something to do with the inequalities of the modern world. To see what it is to want to read disobediently.

At its most enjoyable, Paradise Lost is gloriously and uniquely about disobedience — both in human and cosmic terms. And its greatest pleasures lie in reading and misreading Milton’s marvellous rolling, sonorous, labyrinthine passages in the privacy and sweetness of our own interior, secret, very un-biblical gardens. Clothed or unclothed.

Leave a Reply