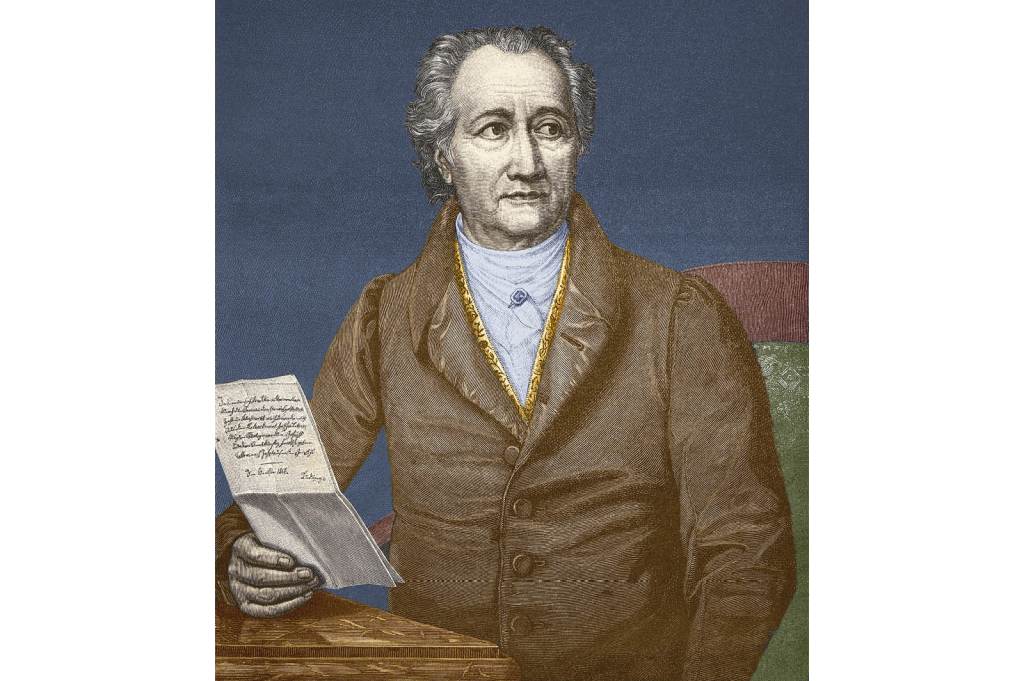

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe bears one of the most famous names in world literature, though he is largely unread by English-speakers. He is most closely associated with the novel and dramatic form, so many would be surprised to know that he primarily spoke of himself, for much of a long life that spanned from 1749 to 1832, as a scientist. He was a pioneering exponent of the science of evolution, and in two wonderful poems, The Metamorphosis of Plants and The Metamorphosis of Animals, he explored his belief that nature evolves from simpler, earlier life forms. This, rather incredibly, was seventy or eighty years before Charles Darwin began to write.

Goethe was a pioneer anatomist, who foresaw, simply from examining a sheep’s skull, the essence of modern neuroscience, namely that signals are sent to the brain through the vertebrae. He was also a geologist of considerable note. His Theory of Colors, in which he pointed out flaws in Newton’s Optics, has gained ground among modern physicists since its publication in 1810. It had an enormous impact on nineteenth-century art; the great artist J.M.W. Turner was an ardent admirer. Later developments in art, through the Impressionists and Expressionists and beyond, owe many of their insights and forms of expression to Goethe.

Goethe achieved all this while being, for most of his grown-up life, a politician and civil servant largely responsible for the administration of the little Duchy of Weimar. In this, he can be compared to the British author Anthony Trollope, who wrote countless novels about the nineteenth-century clergy and politicians while inventing the pillar post box. Goethe took charge of local mines, roadbuilding, the army, the administration of justice and the appointment of church offices. He seldom missed a Cabinet meeting in half a century. Among his duties at Weimar was managing the court theater; he wrote more than forty plays and directed many more, from Mozart operas to the masterpieces of his friend Schiller.

Goethe was an accomplished painter and one of the great collectors of minerals, of medals, of coins and antique sculpture. He was one of the great conversationalists in history, and many have written down his speech, which at times rises to the dialogues of Socrates as written up by Plato.

And, of course, he was a poet. A poet of that rarest of breeds, whom we can place in the same league as Dante and Shakespeare. All his life, Goethe displayed an extraordinary, prodigious lyric gift, and excelled in a wide variety of verse forms.

In my new book about him — Goethe: His Faustian Life — I see this prodigy through the prism of his most famous work. He began writing Faust when he was a young student-lawyer in Strasbourg. He completed the work when he was an old man in Weimar, in his eighty-second year. By then, his whole life experience had been poured into his reworking of the old legend, of the scientist-mage of the Reformation era who went over to the Dark Side.

Goethe, at a very early stage of his writing, developed the traditional Faust story to bring in modern preoccupations. During his life, which spanned the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, he witnessed the great convulsions and revolutions of politics and thought which characterize that era: the American Revolution, the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, the development of modern science, the discoveries of the properties of H2O — which in turn led to the development of steam, and hence of automated industry — the emergence of paper currency replacing the old economic and fiscal systems of the pre-Napoleonic world. All these things, and many more, were poured into his Faust drama. By the end, Goethe realized that the Faust he had created was not so much the autobiography that he had anticipated as a portrait of modern humanity.

In one of the most famous monologues in the drama, Faust thanks the Spirit of Earth that has filled him with curiosity and knowledge about the Natural World. It is a speech which was inspiring to many of the pioneers of modern science, most notably Sigmund Freud and, at a slightly later date Carl Jung, who found in Goethe the inspiration for the art (or science?) of psychoanalysis. But it is also a profound piece of metaphysics. At times, it seems like one of the great nature-monologues of William Wordsworth, but Faust then tells the Earth-Spirit that he needs the sinister-cynical-jokey companion Mephistopheles, who bursts into his life about one-third of the way through part one of the play. What Goethe suggests is that Wordsworthian Nature-Mysticism, and/or scientific analysis (for Goethe part of the same intellectual and spiritual journey) cannot be done in innocence. There is always going to be moral compromise along the way.

Faust anticipates one of his great readers, Friedrich Nietzsche, the author of the ironically titled Beyond Good and Evil. The quest for knowledge; the striving after ever more ingenious inventions and discoveries — neither can be done without moral compromise. This does not make Goethe either a moral relativist or a cynic. He was neither. One of the things which is most apparent when you read Faust is the warmth of Goethe’s imagination. But he was a pragmatist, and he realized that modern humanity was everlastingly compromised. In writing his version of the Renaissance-era mage/scientist, Goethe had depicted humanity in the Age of Science.

It is difficult to think of any area of modern life, from the huge advances in science seen in the last few decades, humanity’s responsibility to the green planet which our ingenuity and industry have all but wrecked, the power politics of would-be world-dominators from Napoleon to Putin and Xi Jinping (who claims, astonishingly, to know Faust by heart!) to the secularization of Western culture and the decline of Christianity — to name only a few huge themes — which are not anticipated in Faust. It is one of the titanic human achievements in literary history, really without parallel. This poem, and the life of the man from whose prodigious brain the poem emanated, is one which I have tried to draw out, and to make available to the present generation of readers. It is their story.

A.N.Wilson’s Goethe: His Faustian Life is published by Bloomsbury Continuum ($35). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply