Almost three decades after the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, it is possible, if not always easy, to see the funny side of the Troubles. Derry Girls, Lisa McGee’s coming-of-age television series, and Milkman, Anna Burns’s surreal novel, wring laughs as well as tears out of mayhem.

There are few laughs in Steve McQueen’s Hunger, which did “for modern film” according to one critic, “what Caravaggio did for Renaissance painting.” For those who prefer horror unmediated by fiction, Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing is the best example of longform journalism since Capote’s In Cold Blood.

But along with their setting, these dazzling creations have something else in common: to get made, they all needed the backing of a producer or publisher from the UK or US.

As the violence settled into a grinding war, poets saw they were living through Tragedy with a capital T

Visitors to Ireland often find it odd, and rather bogus, how little southerners seem to know or care about what happens across the border. If northerners never forget, we in the south affect to be blind. It’s partly defensive, this act. Ireland, a proudly Catholic country in her first decades of independence, was too poor and weak to help our co-religionists over the border. Easier to deal with our own weed-filled garden if we could see or hear no evil over the neighbor’s fence.

That act ended when youthful soixante-huitards challenged inequality from San Francisco to Paris. Catholics who tried marching for civil rights in Northern Ireland had their heads cracked. On Bloody Sunday, 26 unarmed protesters were shot in Derry. Days later, Dubliners burned down the British Embassy. Panicked southern politicians like Conor Cruise O’Brien reimposed silence by fiat.

For the sin of interviewing IRA spokesmen, the board of RTÉ, Ireland’s national broadcaster, were fired. Newspaper editors were menaced with prosecution. These brute tactics instilled fear and deference in the media. Nationalist claims, hitherto heard sympathetically, would now be treated with skepticism – something that came increasingly easy as civilian deaths mounted through the 1970s.

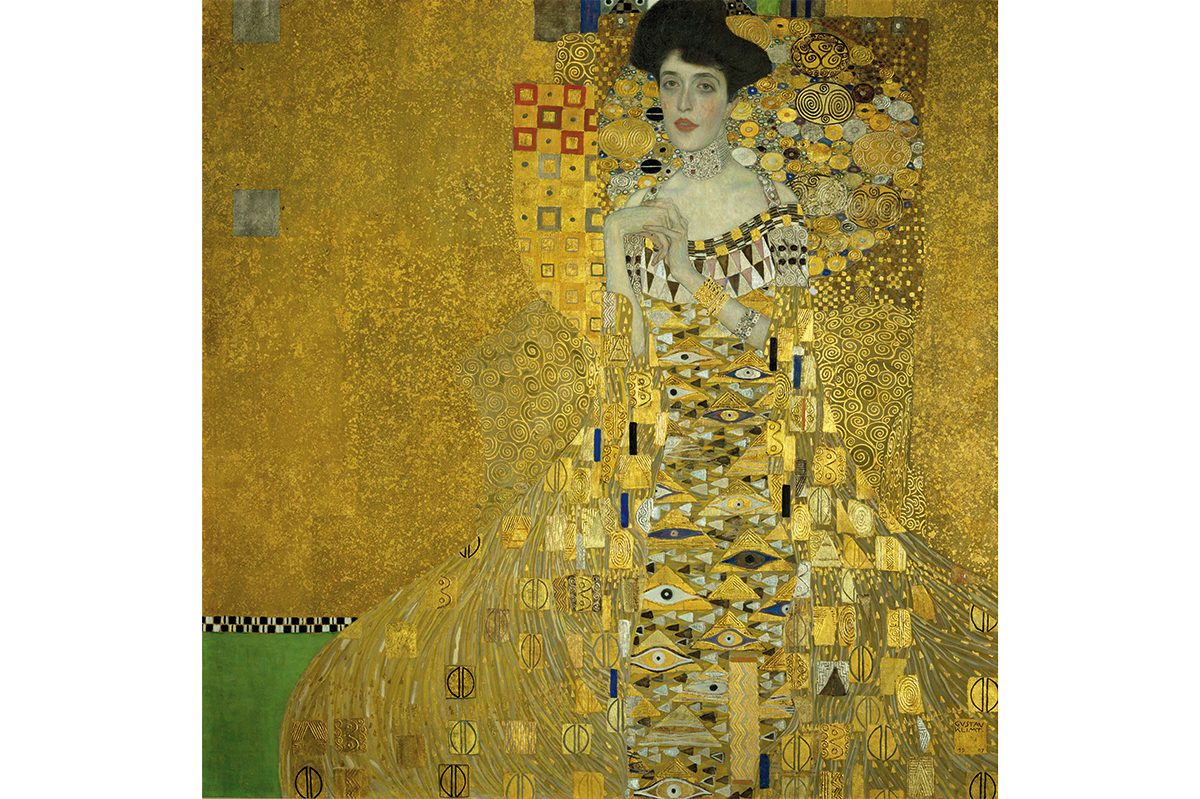

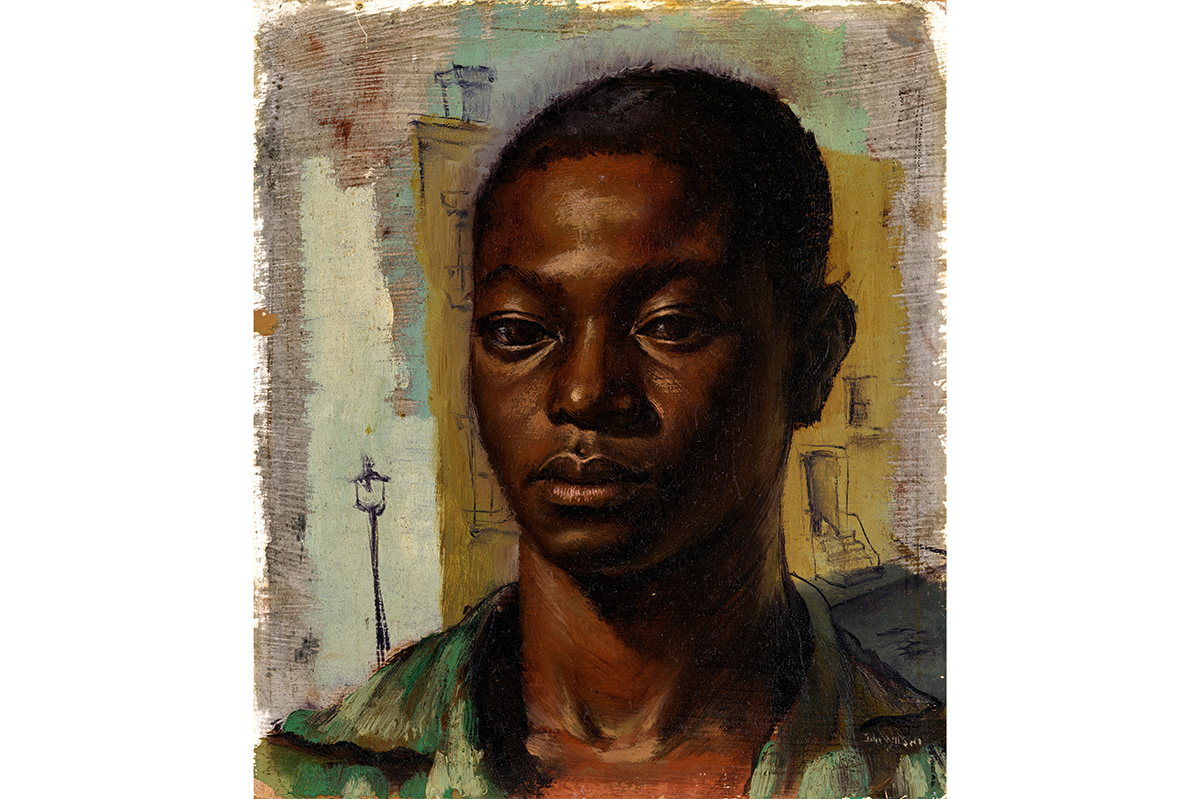

The habit of self-censorship, however, took longer to trickle down to the arts. Throughout the Troubles, sculptors such as F.E. McWilliam and painters like Robert Ballagh felt duty-bound to engage them from their different perspectives.

As the violence peaked and settled into a grinding, long war, poets like Seamus Heaney and dramatists such as Brian Friel recognized that they were living through Tragedy with a capital T. The themes that inspired Sophocles and Aeschylus – guilt, betrayal and murder – could be found with little trouble in the back lanes of Belfast, the glens of Armagh. How to navigate those deep waters, without cheap sentiment or trite polemic, was the riddle that became their life’s work.

There is something pathological about the taboo, given Irish art is awashwith the politics of faraway lands

But sustained empathy takes effort. And when the Peace Process began in the 1990s, at a time when some were predicting the end of history, southern artists who had had their fill of the stuff were glad to turn back to their navels. And here we are. The taboo against facing north, which is now firmly entrenched in Dublin’s cultural salons, serves a narrow political purpose.

Sinn Féin, an essentially northern party in 1998, is today a major force either side of the border. That that reality has affected how we view the peace was never more obvious than in 2023, the Good Friday Agreement’s 25th anniversary. Such was the revisionist spin that one would be forgiven for thinking that John Hume had singlehandedly disarmed the IRA.

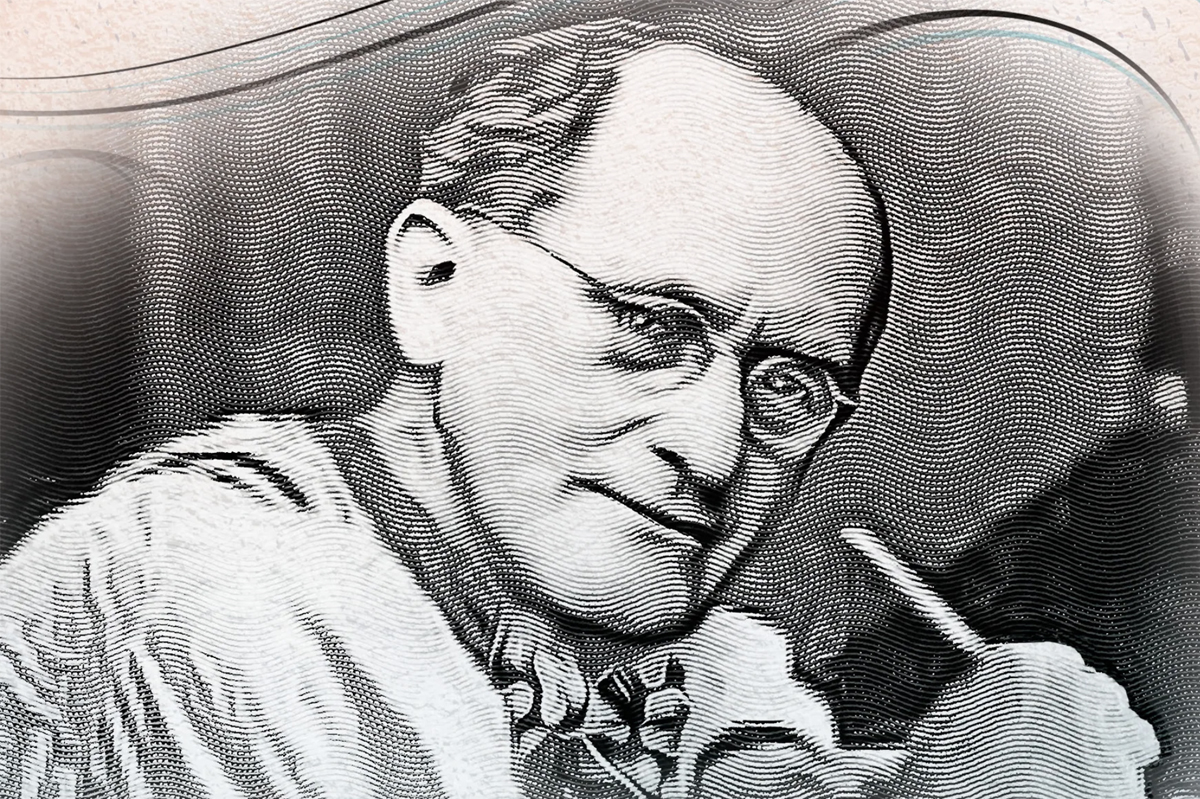

That same anniversary year, I invited Gerry Adams to sit for a portrait. Earlier this year, I had to explain to the Belfast Telegraph newspaper that the bronze bust I sculpted, which was included in spring’s Kilkenny Portrait Show, was not propaganda but rather a “warts and all” portrait of someone who, whatever else, made history.

Given the sensitivities around the man who led Sinn Féin for 35 years, I knew some would doubt my motives. But a few days later, on the radio, I found myself accosted: “Were you not concerned by how well it would be received? Did you think it would be tainted by people’s opinion of him rather than be appreciated as a piece of work?”

The loaded questions put me on the back foot, but I got the point. The Irish are wary of art about the Troubles because we dislike being manipulated as much as anyone. The fact is that Sinn Féin are adept propagandists and have a perennial appeal to young idealists.

The latest iteration of this soft power is Kneecap, the Belfast hip-hop trio that hipsters affect to enjoy. One of the group’s members wears an Irish tricolor balaclava onstage – and in public. A rightly celebrated column by Fintan O’Toole in the Irish Times, titled “Up the ’Ra,” exposed the ignorance that usually lies behind this revolutionary chic: “Up blowing up a young girl who was being collected from dancing lessons by her grandfather, so that her foot was found in a nearby field with the ballet shoe still neatly attached.”

But beyond that performative vulgarity, the taboo against facing north still has force in serious art and letters. McQueen’s Hunger, about the 1981 hunger strike by Irish Republican prisoners in Northern Ireland, could never have been commissioned by RTÉ. That it took a gay, black Englishman to sympathetically dramatize this pivotal moment in recent Irish history is telling. McQueen was angry enough about injustice to eschew any attempt to “tell both sides.” His masterpiece is furiously unbalanced – and all the better for it.

And there is something truly pathological about such a taboo, given that Irish art is awash with politics, all of which concerns far away lands – the USA, Ukraine and, above all, Palestine.

For celebrated Irish authors such as Sally Rooney to hold forth on what she calls “Israeli apartheid” is normal. Yet the people nodding along would be appalled if she spoke in those binary terms about Northern Ireland. Whenever patriotism is considered uncouth, said George Orwell, that thwarted instinct will be “fastened upon some foreign country.” Whose flag is in your bio, comrade?

There are signs that this is changing. Ireland’s former taoiseach – prime minister – Leo Varadkar surprised many in April by coming out of the closet: as a Fenian. “Every generation has its great cause,” he said, “I believe ours is the cause of uniting our island…”

These sentiments would have been most welcome when he held power – but better late then never. That such a canny politician can say this shows the wind has changed. It’s time for Irish artists, too, to turn again and face north.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply