At the start of Elgar’s Second Symphony the full orchestra hovers, poised. It pulls back; and then, like a dam breaking, the music surges forward in wave upon wave of golden sound. ‘Rarely, rarely, comest thou, Spirit of Delight!’ writes Elgar, quoting Shelley, at the top of the score, and you won’t hear that spirit captured more exuberantly than in a performance from May 2009 by the Berlin Philharmonic under its future music director Kirill Petrenko. The violins gleam, the horns swell and every player is audibly leaning into the music. Under Petrenko, Elgar’s leaping compound rhythms almost seem to dance.

The catch, of course — the truth that gives this symphony its universality, and its wrenching emotional power — is that this is pretty much as joyous as it gets. Ahead lies melancholy and splendor, terror and tenderness. Essentially, though, it’s downhill all the way: to twilight, dissolution and a stillness that no one could seriously call peace. The stature of any performance rests upon how the conductor manages that decline, and on that front, I don’t think Petrenko can be faulted. Perhaps it’s a bead of sweat, or perhaps it really is a tear that glints on his cheek as the Berlin violins stream downwards from the crest of the slow movement — but in any case, just listen to the intensity and luster of that string sound!

Petrenko’s deft, restless touch transforms the scherzo into an expressionist nightmare out of Schoenberg’s Vienna (apparently Alban Berg and Egon Wellesz used to play piano-duet versions of Elgar’s symphonies). And at that catch-in-the-throat moment, when the sun sinks behind the rolling hills of the finale and Elgar quietly shows us just how late it really is, the Berlin musicians respond with playing of such translucent, expressive delicacy that it comes as a jolt to learn — from an interview, available as an appendix to the performance on the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall website — that they hadn’t played this symphony in nearly four decades.

Anyway, you can judge for yourself because for an absurdly low fee (and if you’re not by now prepared to pay for your online music, you’re killing the thing you love) the whole performance is there on the Digital Concert Hall to play and play again. My interest in this one was not wholly without prejudice. Since Petrenko was announced as Sir Simon Rattle’s successor in Berlin back in 2015, critics have generally enthused about him, and by any standards he’s a conductor of profound sincerity and musicianship. Yet on the two occasions I’ve heard him live, I’ve been troubled by a sense that his music-making was something so intrinsically private— so wrapped up in his bond with his orchestra — that the audience was effectively shut out.

***

Get three months of The Spectator for just $9.99 — plus a Spectator Parker pen

***

That’s no problem for those who treat classical music like wine connoisseurship, or an academic specialism. It’s less encouraging for those who look to the Berlin Philharmonic as a global standard-bearer for a living artform. Having watched Petrenko on film, I’m still not wholly convinced. But the production values of these filmed concerts are excellent, and the shots from within the orchestra, in particular, show an animated, responsive conductor, with a charisma that’s obviously as clear to the musicians as it is veiled from the audience. I might well be wrong; with some 20 archived concerts by Petrenko available to view, there’s ample scope to explore further.

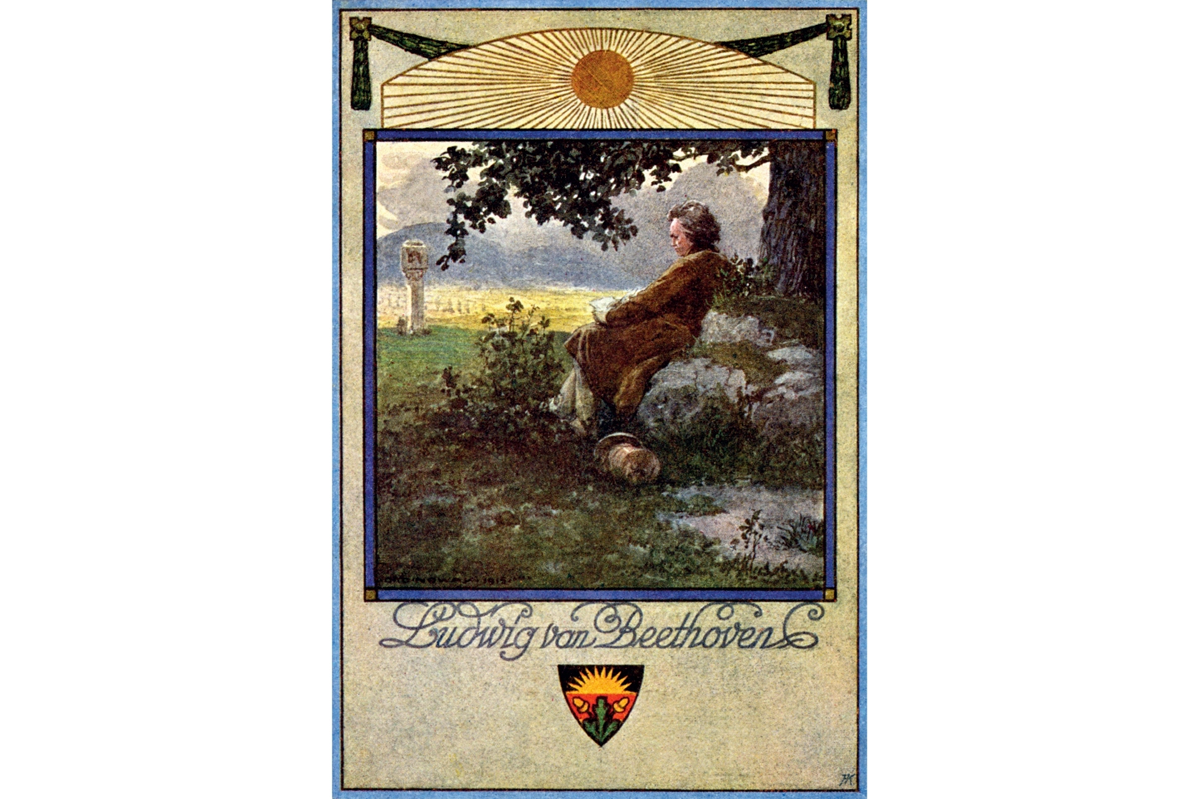

Meanwhile, the Digital Concert Hall offers an impressive spread of archived performances from Petrenko’s predecessors. Rattle conducts a Tom and Jerry soundtrack with the greatest orchestra on earth. Claudio Abbado turns Luigi Nono’s Prometeo into an early-1990s pop video. But if you grew up in classical music’s late imperial era, when Herbert von Karajan glowered from the back cover of every Sunday supplement, there’s no contest. It’s decades since I’ve watched Karajan’s vaguely fascistic studio films of Beethoven symphonies, but the Digital Concert Hall offers a New Year’s Eve gala from 1978. Surely here, captured live, we’ll see Karajan’s old Austrian charm: the lightness of touch, the famous rapport with his world-beating super-orchestra?

The opening bolts of Verdi’s Forza del Destino overture sound like drop-forged steel, and it just gets grimmer. The orchestra is in shadow, with Karajan backlit so his hair shines like a silver halo. Violin bows fall and rise in massed unison and gleaming ranks of trumpets swing into position. But you don’t see the players’ faces — just the maestro, pursed-lipped, drawing sounds of colossal density and fearsome precision from musicians with whom he appears to make no eye contact at all. Only at the end — after Karajan has brought Suppé’s Light Cavalry overture to a climax that could strip the wallpaper of Valhalla — does he crack a smile. It’s appalling; it’s magnificent. But I’m not sure that it’s music.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.