Eight decades after the second world war ended, for how much longer will we produce massive books about Hitler and the Nazis? Richard J. Evans, the former regius professor of history at the University of Cambridge, is one of the senior gardeners in this noxious orchard, having devoted a lifetime’s study to the subject. As a minor under-gardener in the same field, I believe that we now know all we need to about the Führer and the crimes of his vile regime, and, barring the unlikely discovery of something new, it is time that historians moved on.

The damning facts can be briefly stated, and are cogently summed up by Evans in his conclusion: Hitler was a fanatic, brought to power by a German middle class traumatized by defeat in the first world war and the economic woes that followed. Although the Nazis never attained an electoral majority, once in office they destroyed their enemies and demolished the unpopular democracy of the Weimar Republic with ruthless violence. Then Hitler himself, sweeping aside the caution of his conservative generals, embarked on an aggressive and acquisitive foreign policy, leading to a war he ultimately could not hope to win.

The raison d’être underpinning Hitler’s entire life, from his Viennese youth to his last will and testament in the Berlin bunker, was a maniacal antisemitism, horrifically realized in the Holocaust. In this latest, most readable and authoritative book, informed by unmatched knowledge of the vast subject, Evans asks the question: who supported Hitler’s crazed projects and why?

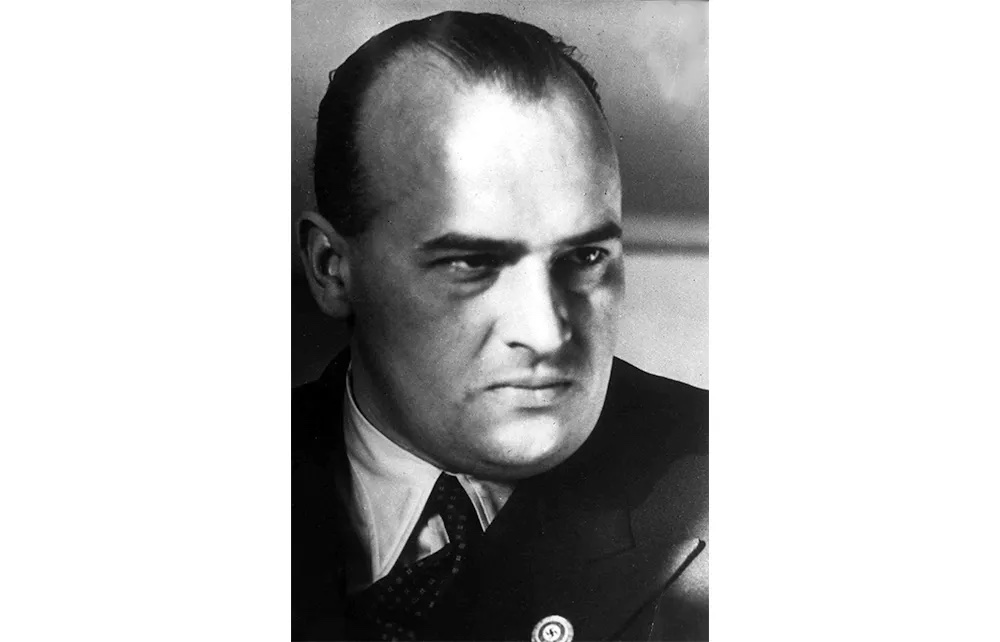

He structures his answer in the form of twenty-three potted biographies — of Hitler himself and a selection of his enablers. These range from the leading paladins —Goering, Goebbels, Himmler and co. — to less familiar names such as Field-Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb and Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, the head of the Nazi women’s organization. Von Leeb rates inclusion as he was typical of the Wehrmacht generals — men who forgot their consciences in the face of Nazi crimes and allowed themselves to be bought off by blatant bribes of cash and country estates. Scholtz-Klink was the embodiment of the ideology of Kinder, Küche, Kirche (she had 11 children) and remained an unrepentant Nazi until her death in 1999, aged ninety-seven.

Leni Riefenstahl, another rare example of a prominent woman in the Reich, was more subtle in dealing with her dodgy past until her death in 2003, aged 100. The brilliant filmmaker prostituted her talent to produce her wildly successful propagandist films of the Nuremberg rallies and the 1936 Berlin Olympics. After the war she unconvincingly denied her part in boosting Hitler, one of her greatest fans, and tried to reinvent herself as a non-political cinematic chronicler of Sudan’s Nuba people. But Evans leaves us in no doubt that Riefenstahl was second only to Goebbels as the regime’s presiding PR genius, responsible for pushing the image of a clean and healthy new Germany on to a gullible world.

Hitler’s people, as chosen by Evans, though varied in their roles and responsibilities, shared some attributes. Many had served in the Great War and had been appalled by Germany’s defeat, blaming the disaster on the Jews. Most were middle class and well-educated; they appeared “normal” and far from psychotic when removed from their jobs as “desk murderers,” organizing the Holocaust and the “T4” euthanasia program of eliminating the many non-Jews considered unfit for the Reich — the mentally ill and physically handicapped, homosexuals, recidivist criminals and nonconformist “asocials.”

One of the worst villains, the corrupt lawyer Hans Frank who ran Nazi-occupied Poland, predicted before being executed at Nuremberg that 1,000 years would pass and still Germany’s guilt would not have passed away. Evans agrees that the generation of Germans born at the turn of the century bore an indelible stain for what they allowed to happen in their name in the 1930s and 1940s. But that generation has now gone.

He closes this moving book with an anecdote and an unanswered question. In the 1970s, traveling on a train, the young Evans met an elderly German lady who told him that she had left her native land for good in 1938 and made a new life in Denmark after her Jewish employer returned bruised and battered from a concentration camp following his expropriation and ruin in the Reichskristallnacht pogrom. Evans writes:

The encounter has haunted me ever since. For if a very ordinary, not particularly intelligent or intellectual or politically engaged young woman had seen what was morally wrong about Nazism and the Third Reich, and taken drastic action as a consequence, why couldn’t other Germans have done the same?

Why indeed?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply