The Artemis rocket is back from the moon. Within a couple of years, if all goes to plan, it will bring men to the moon’s surface. It is a great loss that a bigger deal hasn’t been made of this expedition.

I was only three when John F. Kennedy died, and his famous 1962 pronouncement that we would go to the moon not because it was easy but because it was hard was already history. The picture books I got on birthdays always included him in the history of space exploration. Those books made sure every kid knew how “we” were going to get to the moon. They changed us, and with us, America.

We started with Mercury, baby steps mostly proving we could launch men into space. Then Gemini, a long proof-of-concept program to try out the technology of docking. It only became clear to young me what they were doing many years later; this was an era nearly pre-computer and to see if something would work you had to build it and try it out. Can two spacecraft find each other in orbit and connect? You had to send them up and see what happened. And, as a nation, you had to first believe such a thing was possible.

Then, Apollo. Gas stations back then gave out little prizes to attract customers, and no one did it better than Gulf. With a fill-up, they gave you an actual paper model of the Lunar Lander. I was frustrated to no end trying to assemble it, cutting and folding paper parts. For some reason, instead of the obvious Elmer’s glue, my mother handed me a roll of cellophane tape. The model died a horrible firecracker-related death.

In the 1960s, there were only three TV stations and they all had massive news departments. Almost every family watched “the news.” The people doing all the work were serious journalists, mostly unattractive older men who had learned their craft on radio. They did not seek to shock, and took their roles very seriously. The space program was the biggest story of a generation. Their coverage might have been biased, but it had a big heart.

The unhappy things about rockets were known, too. We had nuclear war drills at school — we’d grab our coats for radiation protection and dive under our desks to wait for the bright flash. Yet little effort was made to explain why Russia would attack our elementary school in Ohio. We were told the exact same rockets the Russians would use to nuke our school were the ones they were using to try to get to the moon ahead of us. America, on the other hand, had developed one set of rockets for peaceful space exploration and another for “defense,” which we never thought through enough to realize involved Russian elementary schools, too.

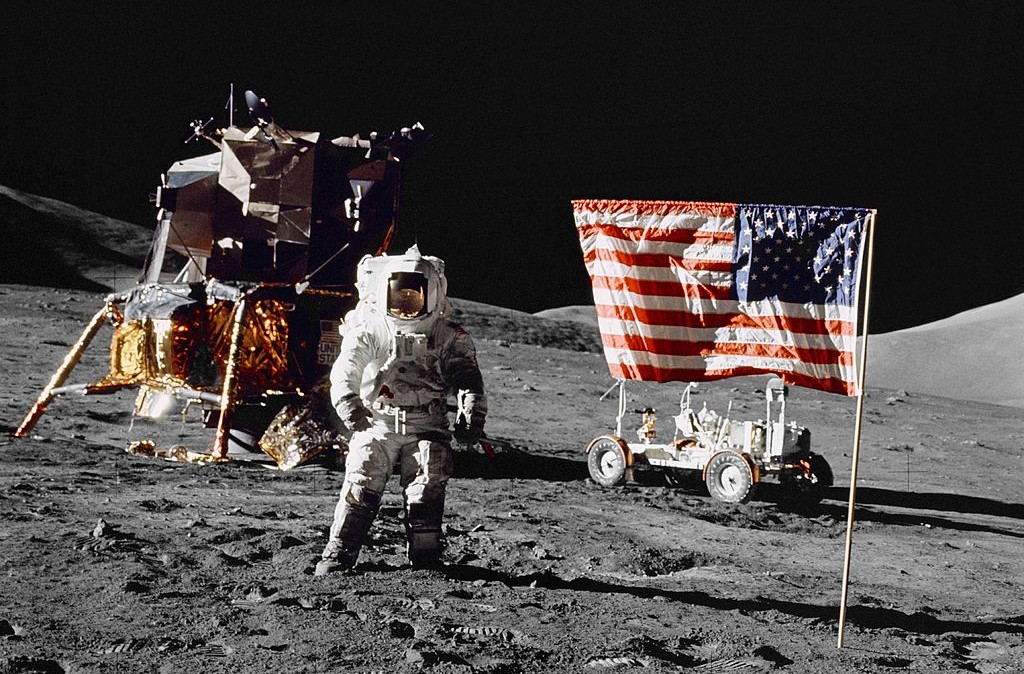

By the time the Apollo program was in full swing, every launch from Cape Kennedy was televised live, and we’d watch from our classrooms. By the time the countdown reached ten, every kid in the room would be chanting the numbers. When the count stopped for a moment to fix some mechanical issue, we’d all let out a disappointed awww… Then, blast off! That night we would all demand to be let into the backyard to stare up at the sky and purr about the astronauts up there somewhere. Someday, “we” would walk on the moon.

Things got completely out of hand in the weeks before Apollo 11, the mission to put men on the lunar surface. Maps of it were in every newspaper, big two-page spreads, and every kid begged for a lunar globe (no one I know ever got one). The news was about this event alone, every page, and every kid soaked it up. We’d gather outside to compare notes, in case someone had picked up a minor detail the others had missed. It was like listening to adults talking serious baseball, all the statistics and photographic details of past games.

I watched Neil Armstrong touch his left foot upon the moon’s surface at 10:56 p.m. on July 20, 1969. I was still too young to understand the questions that are now widely asked. Couldn’t the money have been better spent at home? Did the research really match the outlay, giving us Tang and space blankets but otherwise devoted to expensive manned spaceflight that would soon fizzle out? Wasn’t it all just a big Cold War stunt?

What I remember was a country that saw a single good thing happen together. While in 2022 the majority of young people say they want to be a YouTuber, kids then wanted to walk in space. What if dreams don’t come true? Are we better off for having dreamed them at least for one hot Ohio summer?

For me, it all mattered. I saw something unfold, and I felt like a part of it, however naive it might have been to think that way. It allowed me to see what smart people could accomplish, kind of like climbing a mountain just to do it. I’m much less sure about the greater good, the long-run impact, but I do know I still have something with me from that summer. This isn’t nostalgia; it’s history. Things worked in America back then.

We didn’t yet live in a society that had given up on itself. We put a man on the moon, after all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2023 World edition.