There are many ways to measure the course of human history and each will give an insight into one or more of the various qualities that have made us the most successful great ape. Every major advance, whether in war or art or literature, requires imagination, that most amazing of human capacities, and the ability to ask “What if?” — to take the world from a different perspective.

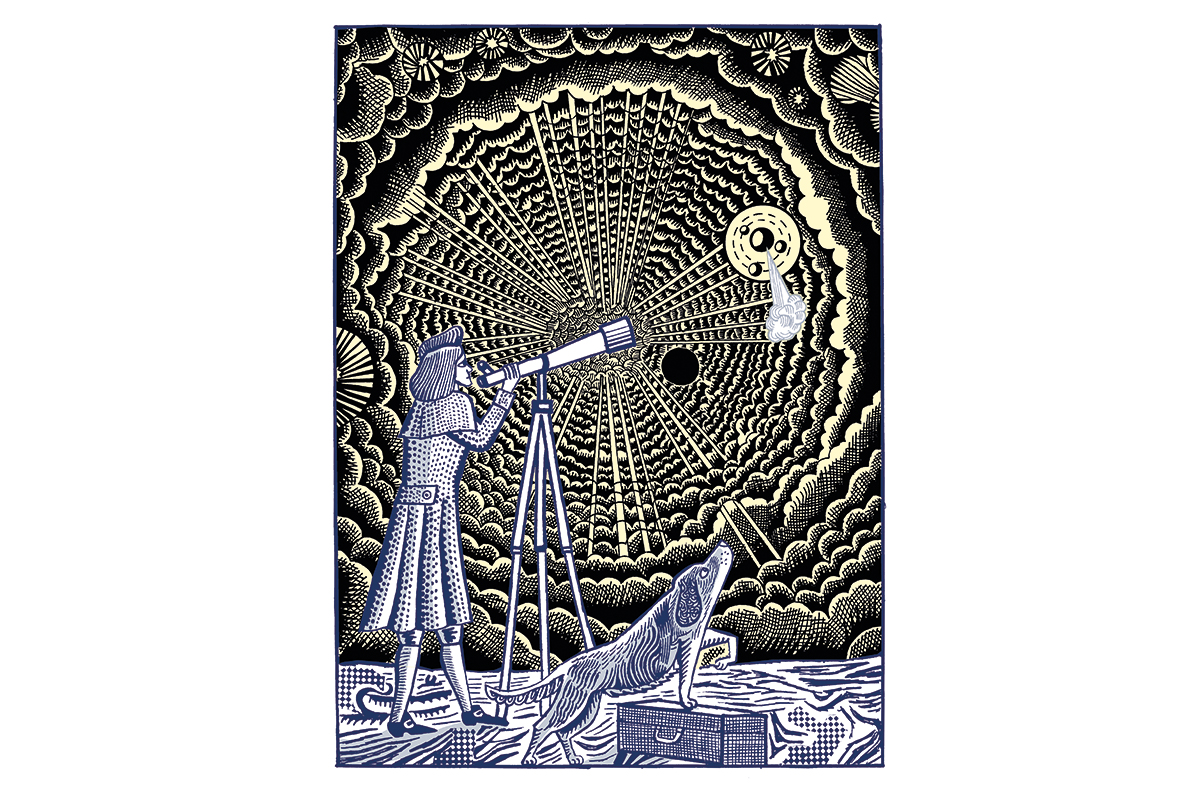

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the history of science. While there is an inherent provincialism in revolutions in art and literature, progress in science is universal, and moves, like Dante’s Hell, in concentric circles of ever deeper understanding. It is the story of human imagination; the progressive casting off of the chains of ignorance, freeing us from our lowly origins and guiding us to Paradise.

Perhaps the greatest revision in our understanding of the universe was Einstein’s discovery that time is just as relative as anything else; and that there should exist points in space with zero volume and infinite density, where time freezes and space stretches out to infinity — black holes. We now have empirical evidence for these wonders, yet despite this comforting reassurance in the scientific method, all the mystery still remains. That they exist means that the breakdown of physics they represent is correct; and the leap of imagination required to explain this is still ahead of us.

This necessary moment of inspiration is the theme of the theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli’s White Holes, in which he offers to guide us, “like Virgil did Dante… to the edge of a black hole’s horizon… down to the bottom, cross through and emerge into a white hole where time is reversed, then go up until we see the stars again.” It is something of a summa of his recent work on the simple hypothesis that “black holes can transform into white,” which he will share with us if we will only give up our “blind confidence in habitual ideas… [for] the world is stranger and more variegated than we imagine.” Once again, we must be willing to ask: “What if?”

But to understand these phenomena it is necessary for Rovelli to ensure we know what black holes really are, and to clarify some common misconceptions about them. For example, we learn that the slowing of time at the horizon (not “event horizon”) of a black hole is purely relational, that time only stops to an observer, not to the person entering: “From close up, the horizon is a normal place.” And that the geometry of a black hole is much more similar to Dante’s Inferno, or “a funnel,” than you probably ever thought — a funnel stretching out to, but not quite reaching, infinity, with a collapsing star at the bottom, “lengthening and narrowing with time.” And the breakdown of physics? Not at the center of the hole, where only a few seconds have passed relative to the millions of years outside. No, this is just a collapsing star, and we understand the physics there. The singularity actually happens in the future, when a black hole becomes “white.”

The book is as much a guide to black holes as white. This is because “a white hole is not another solution to Einstein’s equations. It is the same solution that describes a black hole, reversed in time.” Time, as in Rovelli’s other books, “is always the crux of the matter,” the unassuming protagonist. The equations of Einstein’s relativity are time-invariant (like many things in physics, they work forwards as well as backwards in time), suggesting our Earthly intuition about time as linear and fixed is mistaken, or at least limited.

So, just as you can enter a black hole but not leave it, you can exit a white hole but not enter it. But subtlety is required. Even in reverse, gravity is still an attractive force — “in a film of the solar system running backwards, the sun is still attracting the planets” — and so a black hole and a white hole are, to an external observer, indistinguishable. Time’s “sleight of hand” at the horizon, Rovelli explains, allows them to be the same thing outside but different within; and thus the dual solutions to Einstein’s equations, white and black, can be “stitched together.” As for the singularities that remain (in the future) between these two states, Rovelli guides us gently (there is no mathematics) and gracefully, but also far too quickly, through the requisite quantum mechanics (always fascinating) and the ideas of Penrose and Hawking, to explain the essential and brilliant “quantum leap” that must occur.

But as with much of his work, the literary analogies and references are often repetitive (the analogy to the Divine Comedy runs all through the book, seemingly only to show that he has in fact read it) and imprecise (“information escapes the hole… like Ulysses and his companions escaping the cave of the Cyclops”). Almost every chapter contains some indulgent digression about the power of scientific thinking, or the ignorance of our species, or worse: “To live, to be, as we do, is so sweet.” However, if you can skim read this stuff, what remains is very worthwhile about some new and interesting physics, and it will certainly encourage you to take the world from another point of view. Which is what science is all about.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply