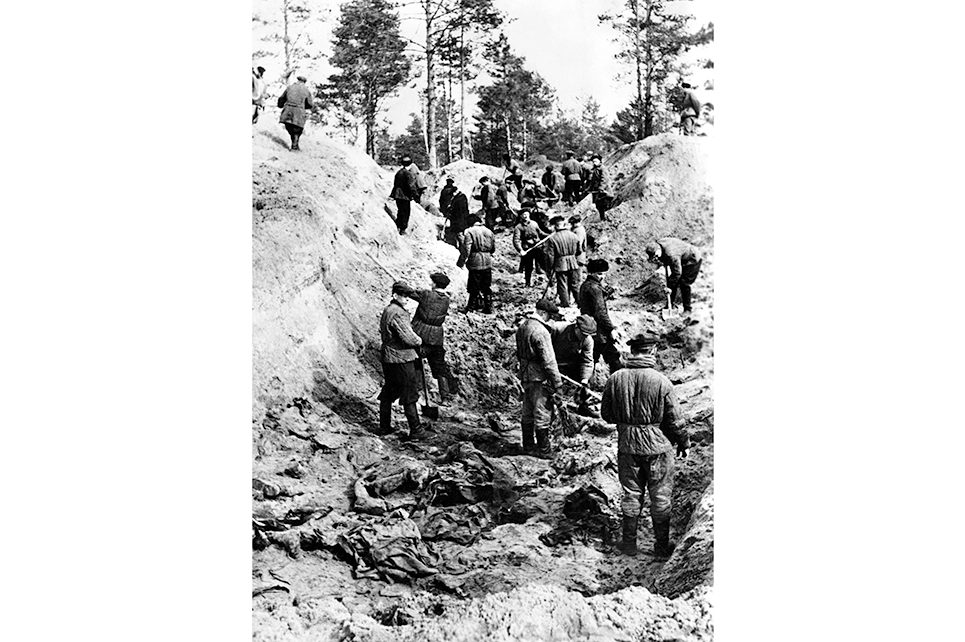

On March 5, 1940, as the USSR stamped its authority on a Poland it had partitioned with Hitler, Stalin signed a decree to murder 14,700 Polish officers in the woods by Katyn. These “hardened, irremediable enemies of Soviet power” were not informed of their sentence and simply shot in the back of the head, a form of execution favored by the secret police, the NKVD, for whom this method was just part of bureaucratic procedure.

When the Nazis turned on the Soviets in 1941 and marched east, they found the mass grave. Goebbels was quick to use the discovery for propaganda purposes and expose the atrocities that the Soviets — the new ally of supposedly freedom-loving Britain — were capable of committing. Whitehall wanted to play down the event, since Churchill was busy making “Uncle Joe” Stalin look less awful. The Poles fighting with the British were understandably appalled.

In 1943, the Soviets retook the Katyn woods. Now it was their turn to lay on a propaganda show quite as effective as Goebbels’s, though with less relation to the facts. NKVD forgers changed the dates on the documents found in the dead officers’ pockets to make it look as if they had been alive when the Germans invaded. They then brought in Western reporters, stationed in Moscow to cover the war, to spread the Soviet version of events. This is the cast of conformists, useful idiots, cynics, adventurers and occasional heroes that populate Alan Philps’s spectacular book, The Red Hotel.

On the train to Katyn the journalists dined on caviar, served on silver plates. But through the lace curtains they could see wounded soldiers, wrapped in bloodstained bandages, being taken on cold freight trains in the opposite direction. When they arrived at the forest, Philps writes, they:

found a forensic laboratory set up in tents amid the snowdrifts, with surgeons sawing open skulls, and the overpowering stench of rotting flesh. The witnesses who testified that the Germans had committed the massacre looked shifty — one of them had been the Nazi-installed deputy mayor of Smolensk, who clearly had been let out of prison on condition he delivered his lines correctly. The reporters were not allowed to put any questions to the people presented as witnesses to the German “crime”… As usual there was an odd array of “performing seals” to add luster to the occasion, in this case Alexei Tolstoy, a pro-Soviet writer known as “Comrade Count,” who was a remote relative of the author of War and Peace, and a bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Those journalists who were skeptical of the “evidence” had their copy amended by the Soviet censors (references to caviar and wounded soldiers were cut). Others were only too glad to support the Soviet “proof.” The BBC’s Alexander Werth was convinced of the Soviet version by the fact that the dead Poles wore boots: if Soviet soldiers had executed them, the boots would have been stolen. Werth also refused to believe that the NKVD would stoop to shooting people in the head — a bizarre assumption, since that was their classic method.

Ralph Parker, of the Times of London, decried the “unhelpful attitude” of exiled Poles over the Katyn massacre, praised Soviet policy in Poland and effused about a “Polish orphanage in the Russian town of Zagorsk, where 100 boys and girls were learning to smile again.” Parker had started off working with the British secret service in Yugoslavia, and when he arrived in Moscow was expected to file pro-Stalinist copy. The Times, writes Philps, was:

a paper noted for accommodating Stalin’s ambitions to exert great power and influence in Europe post-war… When Parker was sent out to Moscow, he was strongly encouraged to present the Soviet attitude “fully and fairly.”

That “full and fair” reporting got Parker an exclusive interview with Stalin, and he was soon in a personal relationship with a female NKVD officer. His material became so pro-Stalin that it was too much even for his editor, and by the end of the war the British ambassador in Moscow refused to meet him, as everything he told him was leaked straight to the Russians. After 1945, Parker left the Times for the Daily Worker, the British communist party paper. In the 1950s he reported on the Korean war, and spread disinformation that the Americans were using biological weapons — a line that is being used again in Kremlin propaganda in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

If Parker comes across as a rogue, the people who emerge from this book with real credit are the Russian fixers and translators, such as Nadya Ulanovskaya, who dared to tell journalists the truth about the Soviet Union and ended up being dragged to the dreaded Lefortovo prison to be tortured into “confessing” to espionage. Philps, a former foreign correspondent, is terrific at training a spotlight on the local staff who are so often forgotten, and exposing the moral ambiguities of journalists.

The Red Hotel reads at first like a World War Two adventure story in the Ben Macintyre mold; but it quickly becomes a merciless dissection of the way in which the media shapes, or rather misshapes, how we see the world, and of the deeply faulty people who produce the stories through which we view current affairs. But it’s impossible to read the book without mentioning one reporter who really was doing his job “fully and fairly” in Russia. On March 30 this year the Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich was detained in Yekaterinburg and charged with espionage. Part of the reason for his arrest was to gain leverage for swapping Russian spies held in the West, part to intimidate other correspondents in Russia. The journalists in World War Two only risked losing their visas if they told the truth. Today, the regime is nastier. Instead of the plush Hotel Metropol — the Red Hotel of Philps’s title — Gershkovich is in Lefortovo.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.