From his base in London, Martin Gayford has spent much of his career as an art critic traveling. He has interviewed and sometimes befriended many leading artists and scrutinized their works close up in their own environment. He has found that artistically creative men and women are not really very different from normal people.

The text of this informative and entertaining book is comprehensively balanced, fair, lucid and subtly witty, although some of the illustrations are handicapped by the smallness of the format. Art criticism itself can be an art. Gayford’s curiosity is wide and his judgments are tolerant, no matter how onerous the investigations can be. He explores remote, uncomfortable places, often accompanied by his wife Josephine, to whom the book is dedicated.

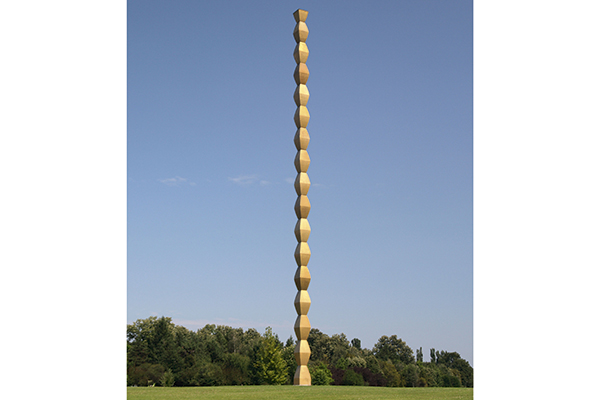

Typical of the arduous journeys that the couple have undertaken in their quest for the basic essences of art is one called ‘A Long Drive to Infinity: Brancusi’s Endless Column’. They were already on holiday in Sibiu, ‘a beautiful old town full of Romanian charm’. Brancusi’s masterpiece, with some of his lesser sculptures in the small town of Targu Jiu, ‘did not look all that far away, at least according to the map’ — only 150 miles deeper into the rural hinterland:

‘The opportunity to visit Endless Column in particular seemed too good to miss, partly because it had the lure of the rare and inaccessible. Although this is among the most celebrated works of the 20th century, almost nobody — in the London art world at least — had actually seen it… Our mad excursion was propelled by my urge to see certain works of art for real. Over the years this impulse has taken us on quite a few quixotic expeditions.’

The reward in Targu Jiu was the chance to find significance in contemplating the soaring verticality of a slender, simply embellished steel monolith, almost 100ft tall. Gazed at upwards from the base, the column did indeed appear to be topless. An order had once come from Nicolae Ceausescu, in distant Bucharest, to demolish the column, as being an example of ‘bourgeois decadence’, but the local mayor found that a Russian tractor was unable to pull it down.

The Gayfords traveled in time as well as space when they went to admire the carved relief of a horse, almost life-size, believed to be 15,000 years old, in a rock shelter at Cap Blanc, Les Eyzies, in the Dordogne.

The range of their search for art has encompassed museums, galleries, churches, mosques, temples and ruins. By looking at works made for ‘completely different reasons by pious Buddhists, Christians, Hindus and Moslems’, one may ‘absorb something of the feelings and attitudes of the original makers’. This nomadic polymath’s impressive curiosity leads him to sculptures in the Annamalaiar Temple at Tamil Nadu, India. An 11th-century bronze statuette of Shiva as Lord of the Dance is a succinct Indian depiction of the joy of godliness.

Conversations with the artist Jenny Saville in London helped extend Gayford’s appreciation of paintings from Titian and Van Gogh to Rothko, Pollock, Bacon and further forward in time. ‘In 2007,’ he writes, ‘I flew 1,200 miles north, almost to the Arctic circle, to look at a collection of 24 subtly different varieties of water.’ ‘Though familiar with the occasional oddities of the avant-garde, comparing very slightly different samples of H20, visually, did strike me as distinctly peculiar.’ His hostess, Roni Horn, an American artist, had arranged this experimental study in the Library of Water in Stykkisholmur, northern Iceland.

Gayford was equally adaptable to sprawling alfresco exhibits on the outskirts of Paris of the art of Anselm Kiefer, a ‘post-cataclysmic romantic’. Conditioned by a boyhood spent in the rubble of the Third Reich, Kiefer sculpted boats, airplanes and books from lead.

We hear of the Sea of Mist from the peaks of Huang Sha, the Yellow Mountain range in China — a sight ‘as fundamental to Chinese culture as the Pantheon to the Greek and the Pyramids to the Egyptian.’ Gayford also attends an exhibition in Beijing of the art of Gilbert and George. Encouraged by their success in Moscow, George regards the idea of Beijing, as ‘appealingly outrageous’. The couple found their reception sufficiently gratifying to celebrate their return to London with the sale of G&G Italian wine, with ‘China 1993, Peking and Shanghai’ and their portrait, in sombre gray suits, on the label.

Perhaps the most instructive chapter concerns Henri Cartier-Bresson. Talking at his home in Paris, the lively 93-year-old expounded his philosophy, Gayford recalls, ‘in a spirit a Zen master would approve’. ‘Thinking is dangerous,’ the great photographer said. ‘I like the way a cat thinks.’ The celebrated moment of truth, when the camera lens must be exposed, ‘requires a mixture of intuitive understanding and spontaneity. You have to relax and concentrate at the same time.’ ‘The subject of longevity came up,’ Gayford remembers, ‘and he reflected: it’s not years, months, hours and minutes, it’s intensity that counts.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.