Fifty-five years after they broke up, what is there left to say about the Beatles? There have been so many books written about the group and so many obsessively detailed websites devoted to exploring every song, every public utterance, every twist and turn in their history, that the average rational man or woman might think they know all there is to be known about them.

Craig Brown’s magisterial 2020 volume 150 Glimpses of the Beatles was a pop-cultural dive into their peerless influence and standing; Ian MacDonald’s still legendary Revolution in the Head dives into the 241 songs that they recorded (although, of course, it should be 242, thanks to the emergence of “Now And Then” in 2023) and does so with grace, intelligence and slightly frightening attention to detail. And McCartney himself analyzed his lyrics in conversation with the poet Paul Muldoon a few years ago, treating them with a sincerity usually reserved for the work of the deceased.

Ian Leslie is unusual compared to most Beatles biographers in that he is not primarily known as a music journalist. His previous books, with titles such as Conflicted and Born Liars, revolve around the study of human psychology. This makes him a fresh and interesting choice to tackle the age-old subject, but I was skeptical, when beginning the book, that even he would have anything original to say.

John and Paul emerge from this as people, not icons, and your grasp of their genius is all the greater for it

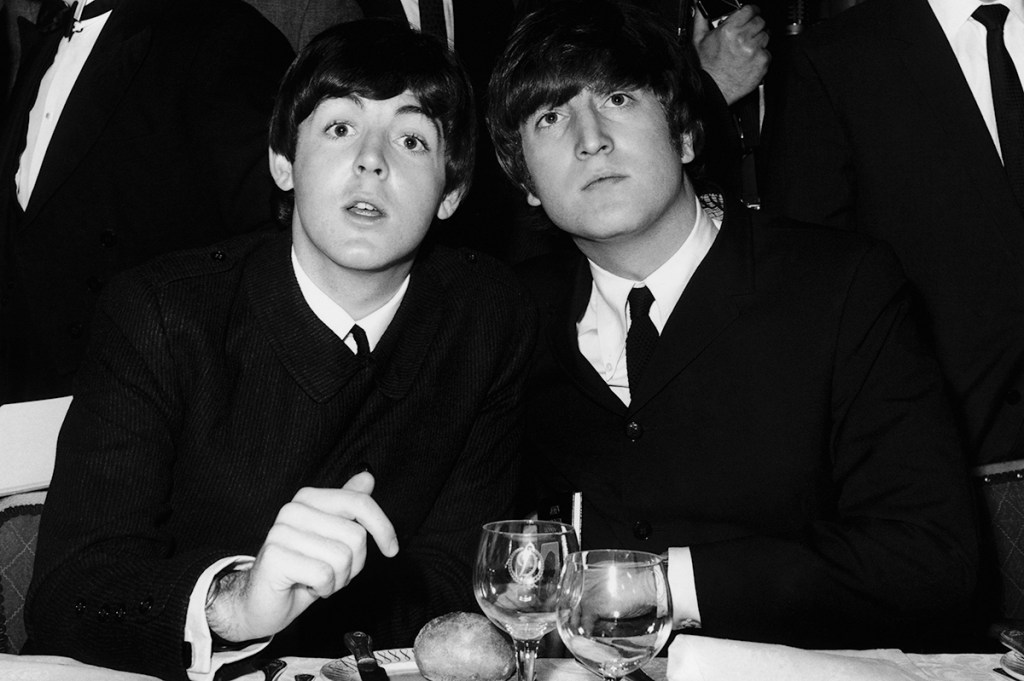

After all, the Beatles legend is now so well-known as to resemble the Bible in its monolithic status. How John Lennon and Paul McCartney met as teenagers at a church fête in Liverpool in July 1957, when Lennon was playing with his band the Quarrymen. How they formed a songwriting and performing partnership, subsequently joined by George Harrison and, eventually, Ringo Starr, that metamorphosed into the most successful pop band that there has ever been. How the pressures of success saw the Beatles first give up live performance and then, beset by the difficulties caused by the death of their manager Brian Epstein and their growing differences in musical and artistic temperament, how they split up in 1970 amid very public rancor and argument. How, eventually, a degree of reconciliation came about between the four that was tragically curtailed by Lennon’s assassination in December 1980.

It’s one of the most eventful narratives in popular music and so well-worn that I approached John & Paul without high expectations. Yet Leslie is a sufficiently gifted writer, both as a marshaler of facts and as a storyteller, that he can, in the words of “Hey Jude,” “take a sad song and make it better.” His innovative, and largely convincing, idea is to regard Lennon and McCartney essentially as platonic lovers. This means that the genius and inspiration of the songs they composed lies in the intensity of the romantic relationship between the two: admittedly one largely driven by Lennon, who is, of course, dead and has not had the luxury of having decades to defend himself or finesse some of his more egregious public remarks.

While John & Paul portrays McCartney in an almost entirely positive light (bar a rather blasé attitude toward romantic fidelity in his pre-Linda Eastman days and occasional shortness toward less brilliant colleagues), Lennon emerges as less talented but arguably more interesting because of, rather than despite, his failings.

I’ve always believed that McCartney was the presiding genius of the Beatles, but this comes down to musical taste. I think the likes of “Penny Lane,” “Let It Be” and most of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Abbey Road are superior to Lennon’s work. Even George Harrison’s finest songs, such as “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and “Something,” give Lennon a run for his money.

Yet Lennon’s 40-year life was a tumultuous, often chaotic one. The son of a mother who was too immature and flighty to bring him up, and who died after being hit by a car when he was a teenager, Lennon concealed his deep-rooted grief and consequent misanthropy underneath a veneer of Liverpudlian wit and detachment. He was belligerent with others, men and women alike, and sought escape in sex and alcohol and then, when he was fantastically wealthy, drugs: he started with cannabis and LSD and eventually became up a rather pathetic figure, strung out on heroin. Ironically, when he worked on his sobriety, recaptured his artistic talent and returned to work, he was shot by an obsessed fan before he could finally make peace with the semi-estranged McCartney, as well as the rest of the Beatles.

Leslie excels at depicting the complex relationship between the two talents, although he provides many points of discussion and debate for fully paid-up aficionados of the Fab Four. He divides the book into brief (and not so brief) chapters, each of which revolves around the discussion of a Lennon-McCartney song. Sometimes, as with most of their early work and “A Day in the Life,” these were true co-creations, but in many other instances, they were fully formed songs worked up by one man or the other.

In some cases, even while in the Beatles, John and Paul existed primarily as solo artists. “Yesterday,” for instance – which Leslie fascinatingly pinpoints as the moment when control of the Beatles slid from Lennon to McCartney – was performed by Paul with an acoustic guitar and a string quartet. In Britain, it was dismissed as an album track, but it became a significant hit in the United States and showed the true versatility of its creator’s talents. Lennon was jealous – and not for the last time.

Leslie picks his material carefully. There is a decent amount on the relationship between Lennon and Yoko Ono, who does not emerge as badly as she did in Brown’s 150 Glimpses, but is still portrayed as almost comically controlling and domineering, dictating how her husband should behave via tarot cards.

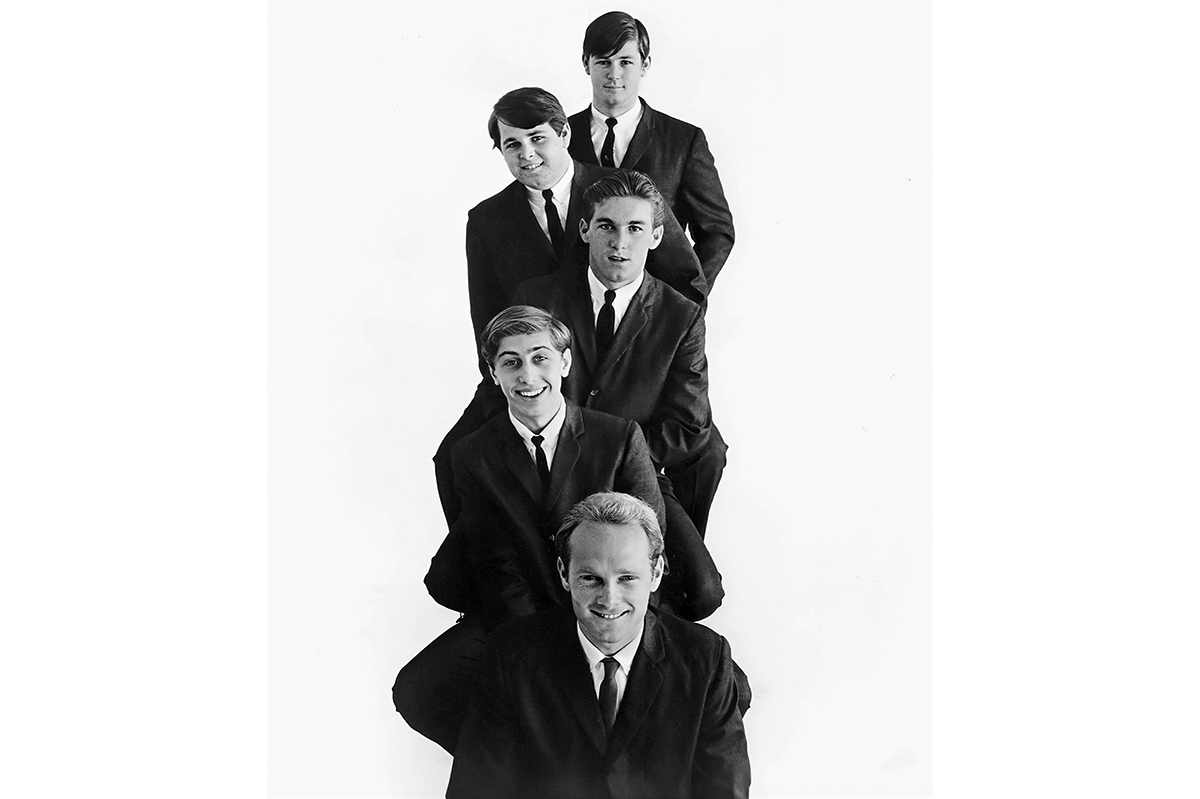

There is rather less on the other Beatles and Ringo, in particular, is reduced almost to walk-on status, with Leslie giving him roughly the same treatment as McCartney’s much-loved sheepdog Martha. Nonetheless, he is generous about Starr’s musical abilities (in a way that many biographers have not been) and Harrison emerges well from the book, too, as a principled, witty man possessed of an extraordinary musical talent that was only stymied by the once-in-a-lifetime fact that he was playing in a band with two even greater talents.

Ringo is given roughly the same treatment as McCartney’s much-loved sheepdog Martha

I have, I must confess, often found it hard to warm to Lennon. Many of the songs are peerless, of course, but “Imagine” remains one of the most false and hypocritical artistic statements ever put out there (a multimillionaire singing “Imagine no possessions” is always going to stick in the throat.) Even in the Beatles, there was an unfortunate tendency to drift off into a kind of mystique. This worked tremendously well for “Tomorrow Never Knows” – which still sounds like the future of music – but by the time Lennon was tormenting listeners with the faux-experimentalism of “Revolution 9” and the psychedelia-by-numbers of “Across the Universe,” it was hard to feel that he had rejected the more classical stylings of McCartney as an act of youthful rebellion, even though he was older than his bandmate. Yet Leslie makes him a complex, sympathetic human being, rather than the saint (or sinner) that he has been so often painted as.

Still, it’s the McCartney show in the end, and once again he has charmed a biographer: a possible reaction to the notoriously anti-Macca Philip Norman claiming that Lennon made up three-quarters of the Beatles. It’s salutary to learn that, as soon as the band had made their first millions, Lennon, Harrison and Starr all fled to their Surrey mansions, as if in fear of what they had unleashed, whereas McCartney threw himself into the heart of 1960s London and embraced the countercultural era that he, as much as anyone, had helped to create.

It is he who has managed to steer the legacy of the Beatles over the past half-century and his well-received, lengthy solo shows offer great pleasure for many, myself included, who were not even born when the band broke up. Yet there has always been a steeliness under the sentiment, a knowledge that a sympathetic and admiring world would turn on him at the slightest sign of weakness.

Leslie begins the book with McCartney, dazed and in shock after the news of Lennon’s death, and unable to say anything more articulate than “It’s a drag,” an unconsciously flippant comment – for which he was pilloried. The author sees it as a cousin to another revelatory remark when the adolescent McCartney was told of his mother’s sudden death after cancer surgery, leading him to blurt out in shock, “But what will we do without her money?” Callous, perhaps, but also an unguarded expression of horror.

And that is ultimately what shines through from John & Paul. There may be other books that are more insightful about the musicology (although Leslie is no slouch in this regard), the biographical details or the gossip. The book does not contain any original material to speak of, and could be regarded as a high-class example of a cut-and-paste job. Yet what it does do, more successfully than any other book about the Beatles I have read, is to humanize its principal architects once again.

You end John & Paul not merely with admiration as to how these two men achieved wonders together, but in understanding of their essential humanity, warped and flawed though it often was. They emerge from this book as people, not icons, and your understanding of their genius is all the greater for it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply