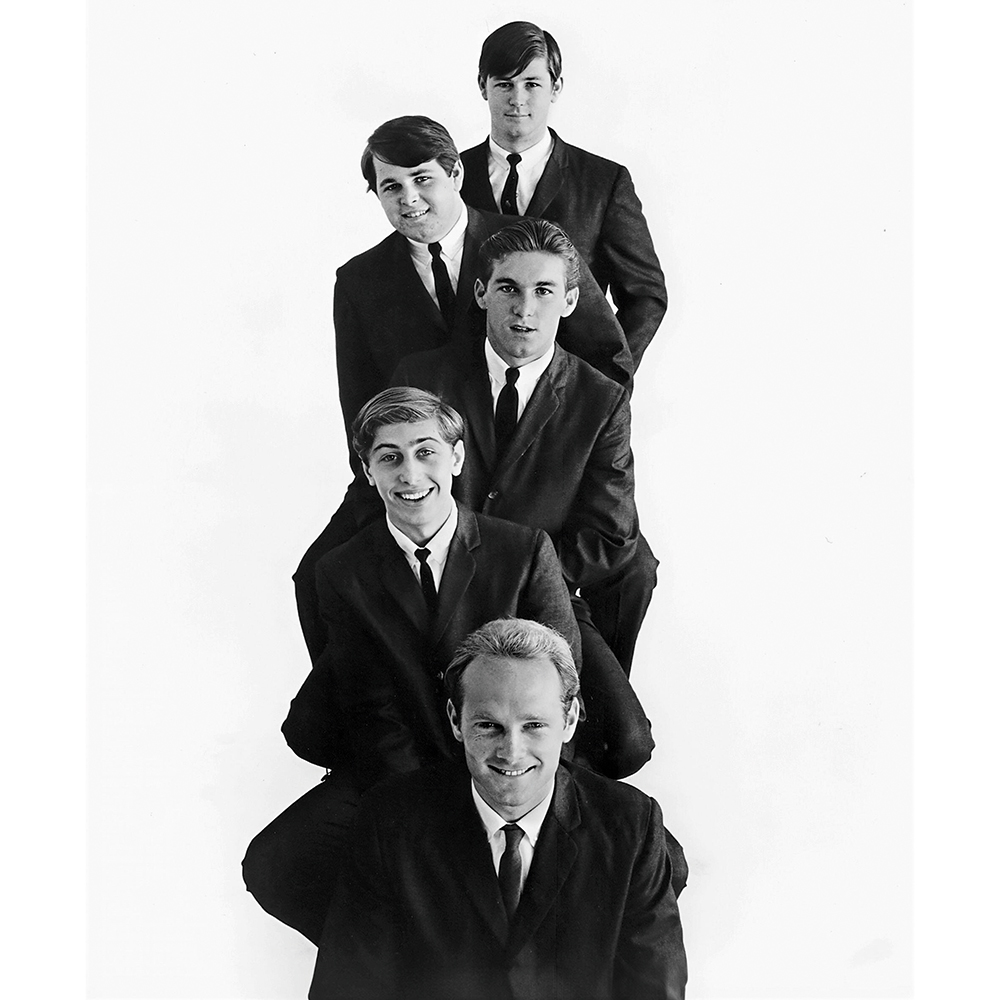

The death earlier this year of Brian Wilson, aged 82, was marked by the usual tributes to a man who was not only a pioneer of popular music, but also a sadly troubled genius whose early years of wild success were quickly overtaken by decades of drug addiction and mental health problems. A recurring theme in the obituaries was what might have happened in the aftermath of the Beach Boys’ masterpiece, 1966’s Pet Sounds, if Wilson, by then the band’s producer and lead songwriter, had not descended almost immediately into narcotic-induced torpor. It has commonly been suggested that Paul McCartney – who revered Wilson – was also jealous of the achievement of Pet Sounds, which arguably overshadowed the Beatles’ Revolver, and that Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was an attempt to reassert the Liverpudlian quartet’s primacy.

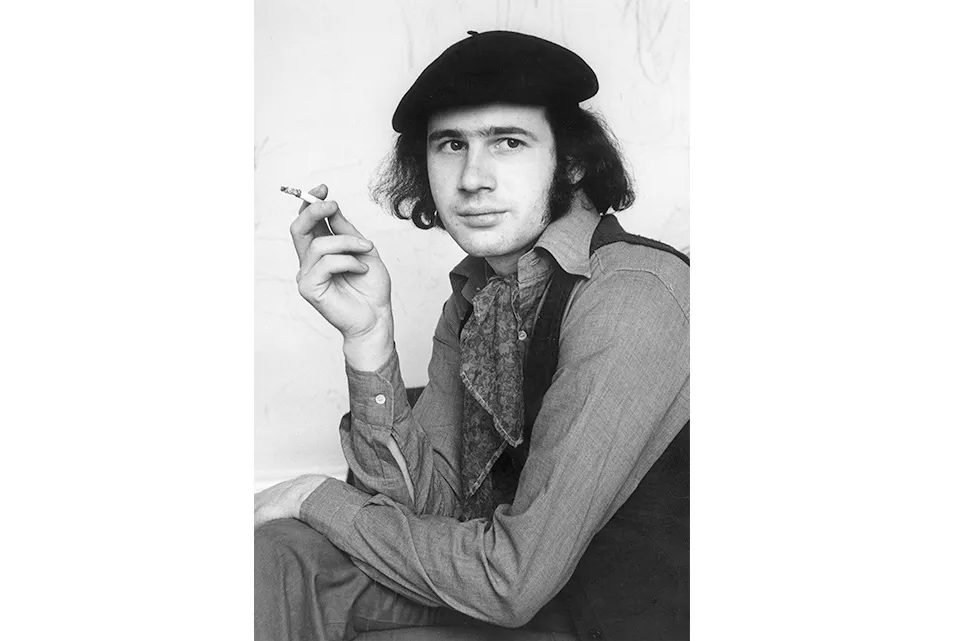

It certainly did so. However, what McCartney may or may not have known was that Wilson had planned a magnum opus that would have made both Sgt. Pepper and Pet Sounds look like amateur dabbling. Entitled Smile and composed and arranged by Wilson with the orchestrator and lyricist Van Dyke Parks, it would have been something unique in the annals of American music. Yet over the abortive 15-month recording process (Sgt. Pepper took more than four), Wilson’s grandiose, envelope-pushing vision came up against his already-fraying psyche, and the result was the most famous unfinished and (initially) unreleased album ever made.

Smile has been a byword for many things in the often-cautious music industry. The first fruits of the recording sessions in 1966, which saw de facto leader of the Beach Boys Mike Love writing lyrics after being sidelined during Pet Sounds, produced nothing less than the single “Good Vibrations,” which was considered too esoteric and avant-garde to be included on the earlier album. It is not hard to see why. Wilson had unwisely begun to dose himself up with LSD, and listened to the similarly expansive and orchestrated work of Phil Spector under the influence of these mind-bending drugs. He started to believe that his role was not simply to be a singer and composer, but to communicate some hitherto-obscure but deeply wonderful cosmic truth to his millions of admirers.

“Good Vibrations” – which itself took seven months to record to Wilson’s satisfaction – was a colossal hit, topping the Billboard charts and the UK singles chart alike, and selling more than two million copies in the first few months of its release. It was a strange but successful mixture of Love’s relatively straightforward and even cheeky lyrics – “excitations” was not commonly believed to be a word beforehand – with Wilson’s extraordinary, baroque improvisations and flourishes. It should have been incoherent and all but unlistenable, but instead it transcended what popular music had previously been capable of. Not everyone was convinced, however. McCartney called it “a great record,” but said it lacked the emotional punch of Pet Sounds, and the Who’s guitarist and songwriter Pete Townshend complained that “‘Good Vibrations’ was probably a good record but who’s to know? You had to play it about 90 bloody times to even hear what they were singing about.”

Nonetheless, emboldened by the conspicuous success of what was intended to be Smile’s first single, Wilson began to come out with increasingly bizarre ideas as to what the album should be like. Announcing, under the heavy influence of drugs, that it would be “a teenage symphony to God,” he also suggested that it would be influenced by American popular music, history, the occult and Manifest Destiny. Sonically, he wished to move beyond the traditional harmonies and surf music that the Beach Boys were synonymous with in favor of a shifting, innovative sound that would owe debts to everyone from George Gershwin and Charles Ives to Disney cartoons and avant-garde jazz. It was a mark both of Wilson’s ambition and his declining mental state that he imported huge quantities of sand into his dining room, so that he could sit at the piano and feel the grains shifting between his toes. He claimed it brought him closer to nature.

Capitol Records, which intended to release the album, knew little of this. It assumed that Smile would be released in early 1967, designed a logo and assigned it a catalog number. Unfortunately, amid significant in-fighting with the band (not least Love, who, wearying of his reduced status, kept pressuring Wilson to release a proper album and to leave aside “the experimental shit”), it swiftly became clear that the Beach Boys were unable to come together to finish the record.

When the Beatles released “Strawberry Fields Forever” and its superior, underrated A-side “Penny Lane” in February 1967, it seemed as if they had usurped much of Wilson’s creative spirit, and the advent of Sgt. Pepper on June 2 in the United States ended Capitol’s interest in indulging the project any longer. The Beach Boys were curtly informed to put out another single – which duly followed, in the form of “Heroes and Villains” – and then to release whatever they could scrape together, so that the huge amount of money and time spent on the recording process was not entirely wasted.

Smiley Smile from 1967 was not regarded with the same enthusiasm that Pet Sounds was. Wilson all but abandoned it to his bandmates (tellingly, the production credits read “The Beach Boys”) and although it has enjoyed a latter-day reappraisal as a chill-out comedown album, it was a strangely unfocused and soporific record. Listening to “Heroes and Villains” in this bowdlerized, unsatisfying form, when compared to the Spector-esque production that Wilson had originally intended for Smile, is all that the average listener needs to do in order to dismiss the album.

Its architect, despairing of the music industry and its machinations, became a suicidal recluse, bingeing on drugs, alcohol and food. He was occasionally seen “in the back of some limousine, cruising around Hollywood, bleary and unshaven, huddled way tight into himself,” according to the journalist Nik Cohn. He underwent breakdown after breakdown and spent most of the next few decades unable to produce any significant music, despite the entreaties of his bandmates and record companies. The albums he did record were scrappy, forgettable affairs that relied heavily on cowriters.

There was litigation with the Beach Boys (especially Love) over who owned the rights to what, but Wilson was regarded as a spent creative force who had never really come out of his sandbox. He showed no signs of ever recapturing the Pet Sounds and Smile genius.

Something shifted at the beginning of the millennium, not wholly to Wilson’s advantage. He was prevailed upon in the early 2000s to perform Pet Sounds, backed by an orchestra, and although the tour was critically acclaimed – albeit with surprise that Wilson was still capable of making music – it lost money because of the expensive musicians. However, in 2004 Wilson returned to the Royal Festival Hall in London to perform Smile for the first time with a stripped-down (but still sizable) band, which did a magnificent job of returning the album to its origins, taking the lackluster production of Smiley Smile away and bringing in an appropriate Wall-of-Sound level of grandeur to it. Unfortunately, Wilson was clearly incapable of appreciating it. A gargantuan, obviously uneasy figure whose painfully scripted banter had to be read from a teleprompter, he was moved into position by his bandmates and sang in a staccato bark that bore little resemblance to the more tuneful vocals of his heyday.

The result was a final, belated release of the album, now entitled Brian Wilson Presents Smile. It was a finely tuned, carefully put together release that gave an infinitely better idea of what Smile would have sounded like if it had come out in 1967 rather than the compromised version. Critics greeted it with a mixture of amazement and relief, hailing it as the finest version of a once-lost album that we were now ever likely to get. Only Wilson’s singing was a reminder that the once all-conquering musician was now a diminished figure. When a 2011 compilation, The Smile Sessions, was released, complete with his more tuneful youthful vocals, it managed to give a moving and even uplifting insight into the sheer level of genius that Wilson was capable of in his heyday.

The tributes after Wilson’s death all mentioned Pet Sounds, “Good Vibrations” and the years of mental illness and personal havoc. Some were kinder than others, but all agreed that Brian Wilson was a musical genius who was ultimately crushed by the sheer weight of his imaginative talent. In the various forms of Smile, incomplete and compromised though most of them necessarily are, we can see the purest form of Wilson’s songwriting ability and we should marvel that any man, let alone a troubled 24-year-old, was capable of such work.

McCartney, for one, might be very grateful that the album never came to fruition at the time, as otherwise he would have had a serious rival on his hands for the title of “greatest pop writer of the century.” Smile shows us exactly what genius, in its untidy, unfinished glory, can be capable of.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply