Society seems to be growing steadily crazier. And maybe it doesn’t just seem to be. Maybe it actually is growing crazier. In the 1930s, science-fiction writer Robert Heinlein dubbed the early 21st century ‘the Crazy Years’, a time when rapid technological and social change would leave people psychologically unmoored and, frankly, crazy. Today’s society seems to be living up to that prediction. But why?

I recently read James C. Scott’s Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. One of the interesting aspects of the earliest agricultural civilizations is how fragile they were. A bunch of people and their animals would crowd together in a newly formed city. Diseases that weren’t much of a threat when everybody was out hunting and gathering over large areas would suddenly spread like wildfire and depopulate the town almost overnight. As Scott writes, an early city was more like a (badly run) refugee camp than a modern urban area, with people thrown together higgledy-piggledy with no real efforts at sanitation or amenities. He observes that the pioneers who created this ‘historically novel ecology’ could not possibly have known the ‘disease vectors they were inadvertently unleashing’.

Then I ran across this observation on Twitter: ‘The internet is rewiring brains and social relations. Could it be producing a civilizational nervous breakdown?’ And I saw another article noting that depression in teens skyrocketed between 2010 and 2015, as smartphones took over. It made me wonder if we’re in the same boat as the Neolithic cities, only for what you might call viruses of the mind: toxic ideas and emotions that spread like wildfire.

Social media is addictive by design. The companies involved put enormous amounts of thought and effort into making it that way, so that people will be glued to their screens. As much as they’re selling anything, they’re selling the ‘dopamine hit’ that people experience when they get a ‘like’ or a ‘share’ or some other response to their action. We’ve reached the point where there are not merely articles in places like Psychology Today and The Washington Post on dealing with ‘social media addiction’, but even scholarly papers in medical journals, with titles like ‘The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large scale cross-sectional study’. One of the consulting companies in the business of making applications addictive is even named Dopamine Labs, making no bones about what’s going on.

In engineering parlance, the early blogosphere was a ‘loosely coupled’ system, one where changes in one part were not immediately or directly transmitted to others. Loosely coupled systems tend to be resilient, and not very subject to systemic failures, because what happens in one part of the system affects other parts only weakly and slowly. Tightly coupled systems, on the other hand, where changes affecting one node swiftly affect others, are prone to cascading failures. Usenet was one such system, where an entire newsgroup could be ruined by a spreading ‘flamewar’. If a blogger flamed, people could just ignore the blog; when a Usenet user flamed, others got sucked in until the channel was filled with people yelling at each other. As Nick Denton wrote, the blogosphere ‘routes around idiots’ in a way that Usenet didn’t, because the blogosphere doesn’t depend on the common channel that a Usenet group did.

Social media – especially Twitter – is more like Usenet than blogs, but is in many ways worse. Like Usenet it is tightly coupled. The ‘retweet’, ‘comment’, and ‘like’ buttons are immediate. A retweet sends a posting, no matter how angry or misinformed, to all the retweeter’s followers, who can then do the same to their followers, and so on, in a runaway chain reaction. Unlike blogs, little to no thought is required, and in practice very few people even follow the link (if there is one) to ‘read the whole thing’. According to a study by computer scientists at Columbia University and the French National Institute, 59 percent of people who share a link on social media don’t read the underlying story. I’m honestly surprised the number isn’t higher.

People are more likely to believe misinformation on social media. They tend to only read headlines that mesh with their preconceived ideas, and they tend to get and share those headlines from friends, family, or people they see as ideological allies. This makes them less critical and more willing to pass on things that on further thought they would probably recognize as bogus. In addition, of course, social media passes along only tiny niblets of information, allowing and even encouraging people to make assumptions about the background, assumptions that also tend to follow their preconceptions and prejudices.

Right now, it almost seems as if the social media world was designed to spread viruses of the mind. And that’s probably because it was. While in the earlier days of the internet, ideas spread faster than before, today in the walled gardens of social media outlets like Facebook, Instagram, or especially Twitter, ideas spread much, much faster, and with less time for rumination or consideration, than ever before. And that’s by design, as social media companies use algorithms that promote posts based on ‘engagement’ – which typically means users’ emotional reactions – and ‘share’ buttons allow each user to pass them on to hundreds or thousands of friends, who can then do the same. This repeated sharing and resharing can produce a chain reaction reminiscent of a nuclear reactor with the control rods removed.

As Jaron Lanier writes:

‘Engagement is not meant to serve any particular purpose other than its own enhancement, and yet the result is an unnatural global amplification of the “easy” emotions, which happen to be the negative ones…Remember, with old-fashioned advertising you could measure whether a product did better after an ad was run, but now companies are measuring whether individuals changed their behaviors, and the feeds for each person are constantly tweaked to get individual behavior to change…The scheme I am describing amplifies negative emotions more than positive ones, so it’s more efficient at harming society than at improving it.’

It’s unfortunate that social media not only makes informed debate more difficult on their platforms, but also, it seems, rewires people’s brains in such a fashion as to make such debate more difficult everywhere else. This is made worse by the fact that Twitter in particular seems to be most heavily used by the very people – pundits, political journalists, the intelligentsia – most vital to the sort of debate that Emerson saw as essential.

In fact, the corruption of the political/intellectual class by social media is particularly serious, since their descent into thoughtless polarization can then spread to the rest of the population, even that large part that doesn’t use social media itself, through traditional channels. Writing on why Twitter is worse than it seems, David French observes that even though its user base is smaller than most other social media, those users are particularly influential:

But in public influence Twitter punches far above its weight. Why? Because it’s where cultural kingmakers congregate, and thus where conventional wisdom is formed and shaped — often instantly and thoughtlessly.

In other words, Twitter is where the people who care the most spend their time. The disproportionate influence of microbursts of instant public comments from a curated set of people these influencers follow shapes their writing and thinking and conduct way beyond the platform.

It’s tempting, when reading a news feed full of rage and hysteria, to console yourself in the knowledge that it’s ‘just Twitter’. But behind those angry, hyperbolic tweets (well, the blue-check-marked ones, anyway) are people, and those people are disproportionately the most engaged and most influential men and women in American public life. It’s ‘just’ the American political class putting its rage and intemperance on display, hoping to remake the world in its own irate image. And the surprising success of that attempted makeover should scare you, whatever your own political views are.

Twitter is also the most stripped-down of the social media, and thus the most illustrative of social media’s basic flaws. Just as sad people repetitively pulling the levers on gas-station slot machines illustrate the essence of gambling without the distracting glamor of casinos and racetracks, so Twitter, without a focus on ‘friends’ or photos, or other sidelines, displays raw online human political nature at its worst. This makes it easy for people to get worse.

You can reject Twitter’s toxicity by leaving the platform, as I did in the fall of 2018. But French is right that this doesn’t really solve the problem: ‘Absent large-scale collective action by the political/media class to reject the platform, simply logging off Twitter is merely a personal defensive mechanism — a sometimes necessary mental-health break that all too often correlates with diminished influence in the national political debate.’ With Twitter, you can participate and be driven crazy – or you can stay sane, and lose influence. That’s a bad trade-off.

Leaving aside various forms of content regulation, is there anything else that can or should be done?

Well, we might better achieve the goals of regulation by regulating something other than speech. Although antitrust is out of fashion, the huge tech companies constitute interlocking monopolies in various fields, and often support one another against competitors – as Paypal, for example, cut off money transfers to YouTube competitor BitChute, and Twitter competitor Gab.

Antitrust regulation would also dilute the political power of these big companies, and that’s a real issue. Old-time monopolies like those broken up by Teddy Roosevelt concentrated economic power (in industries like railroads, steel, or oil) and gained political power as a result. But the very nature of social media companies’ monopolies amplifies their political power even before they start hiring lobbyists. As Columbia Law Professor Tim Wu notes in his new book, The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age, industry concentration leads to political corruption:

‘Big monopolies aren’t just an economic threat: they’re a political threat. Because they’re largely free of market constraints, they don’t have to put all their energy into making a better product for less money. Instead, they put a lot of their energy into political manipulation to protect their monopoly.’

‘Big tech is ubiquitous,’ Wu writes. It ‘seems to know too much about us, and seems to have too much power over what we see, hear, do, and even feel. It has reignited debates over who really rules, when the decisions of just a few people have great influence over everyone’.

Rather than focusing on the content of what individuals post on social media, regulators might better focus on breaking up these behemoths, policing anticompetitive collusion among them, and in general ensuring that their powers are not abused. This approach, rooted in antitrust law, would raise no First Amendment or free speech problems, and would address many of the most significant complaints about social media.

We’ve now reached the point when even Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes is calling for a breakup. Maybe it’s time.

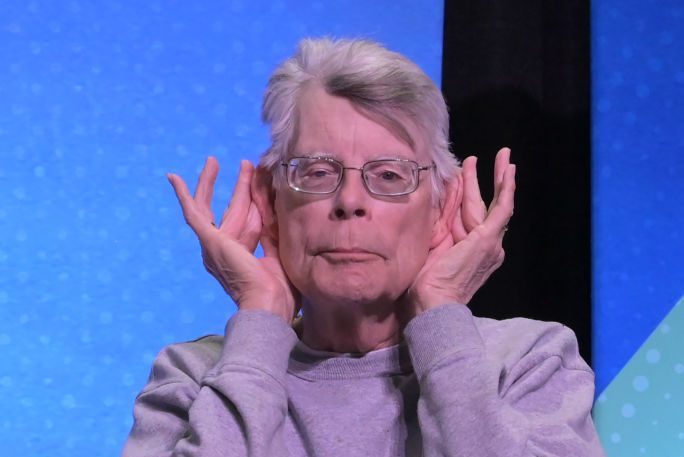

Glenn Harlan Reynolds is a professor at the University of Tennessee College of Law, and maintains the politics blog, Instapundit. This excerpt is taken from The Social Media Upheaval (Encounter Intelligence).