The tramp of lovers marching through our heroine’s bedroom in the first half of Sonia Purnell’s Kingmaker almost deafens the reader. But then not for nothing did Pamela Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman become known as the alpha courtesan of the 20th century. What is perhaps not so well covered is her decade-long influence on American politics before becoming the United States Ambassador to France under (no, not literally) Bill Clinton.

The Hon. Pamela Digby was born on March 20, 1920 and brought up quietly in Dorset, riding, hunting and meeting only those her parents (her father was the 11th Baron Digby) considered above the social plimsoll line. Early on she realized that what gave a woman supreme independence was great wealth — usually acquired through a man.

After a humiliating first season — she was thought too plump — she accepted the proposal of the appalling Randolph Churchill, who thought he might be killed in the forthcoming war and wanted to ensure an heir first. Almost at once she became a great favorite of his parents, Winston and Clementine, and adored them in turn. Politically aware and interested from the start, she found herself in the right place at the right time. At first she did her best to be a supportive wife to the gambling, womanizing, hard-drinking Randolph, producing the required heir, young Winston, in October 1940.

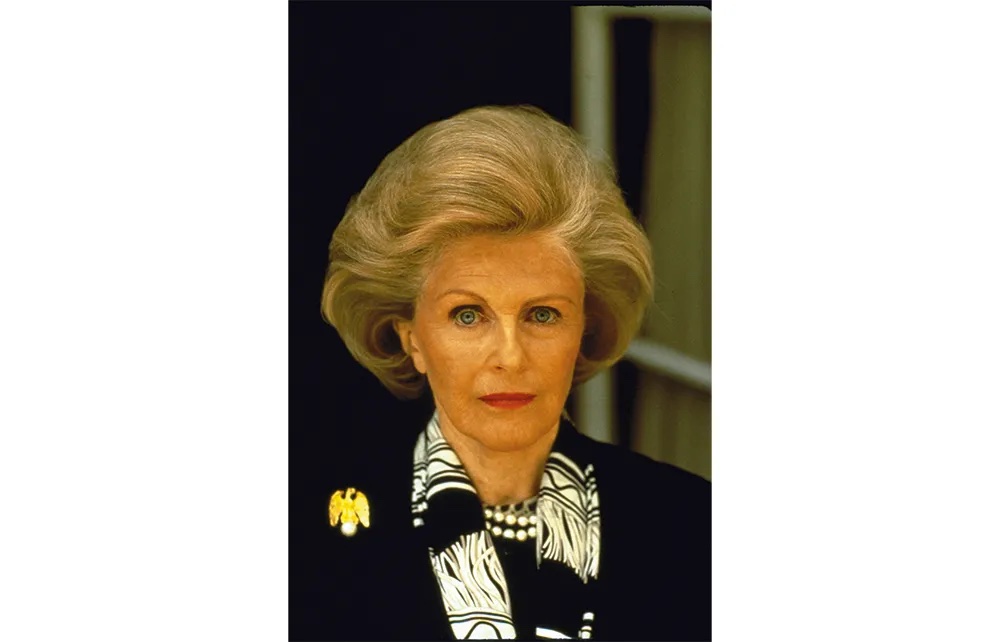

She was not much of a mother, but by now she had turned herself into a seductive beauty, with dark red hair, perfect magnolia skin, compelling sapphire blue eyes and a sumptuous figure — later, her fitter at Dior said she had the most beautiful breasts she had ever seen. To add to the mix, she had, like Truman Capote’s heroine Holly Golightly, taught herself to like older men, offering them, writes Purnell, “a rare cocktail of flattering attention, smoldering sex appeal and an impressive grasp of geopolitics.” It was a formula that would stand her in good stead all her life.

Churchill was desperate for America to enter the war and any influence that could be brought to bear on visiting Americans was vital. As the bombs rained down on London during the Blitz, Pamela’s career as a femme fatale took off, subsidized to the tune of £3,000 a year by Lord Beaverbrook, the immensely rich press baron who had spotted her potential, and who helped by taking in little Winston and his nanny at his country home, Cherkley.

The first target was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s special envoy Averell Harriman, in Britain to supervise the Lend-Lease. At a private dinner at the Dorchester, Pamela, in a strapless, skin-tight gold lamé dress (bought for the occasion by Beaverbrook, who had also arranged the seating plan), sat next to the 49-year-old Harriman. By the time dessert was served, he had invited her to his suite so that they could “talk more comfortably.” As the gold dress slithered to the floor, it is safe to say that geopolitics was not up for discussion. Harriman was swiftly recruited as a member of Churchill’s inner circle, facilitating aid from America and speaking up for Britain wherever possible.

Soon Pamela was living in a flat on the top floor of the American embassy, then in Grosvenor Square, the lease taken out in Beaverbrook’s name but the rent paid by Harriman. So delighted were the Churchills with Pamela’s efforts on behalf of Britain that they began paying her £500 a year, which they continued for the rest of their lives.

When Harriman was posted to Moscow, it was the turn of the plutocrat Jock Whitney, followed by the broadcaster Ed Murrow, generals galore and even an Englishman or two; “Peter” Portal, then head of Bomber Command, who wrote Pamela 30-page letters, was one. Somehow she managed to run what Purnell calls “a network of men,” corresponding regularly with any who were away. Outside were ruined buildings and rubble; inside, all was warmth and luxury. At her five-course dinner parties, food was plentiful, since her American admirers kept her supplied with steak and champagne. With the aura of the Churchill name, couture clothes and glowing beauty, the 22-year-old Pamela dazzled, as she carefully filed away tidbits of information to pass on later. As one American journalist put it after watching her at work: “She became a catalyst on a hot tin roof.”

By 1945, Pamela’s “war work” was at an end. “I am afraid of not knowing what to do in peacetime,” she wrote to Harriman. The answer that soon emerged was more of the same. The first step was an uncontested divorce from Randolph; then a rekindling of the affair with Harriman when he returned to London as ambassador. But when he obtained the US cabinet post he had always craved, he went back again to Washington, his wife and a life free of scandal. Fortunately for Pamela, Prince Aly Khan, the playboy son and heir of the Aga Khan, appeared. He honed her sexual technique (“Always keep a bucket of ice cubes by the bed,” he advised), but he was soon succeeded by Gianni Agnelli, the heir to Fiat, Italy’s largest corporation.

Pamela loved Gianni, who gave her a “wonderful” Paris apartment, a butler and a blue Bentley and chauffeur, as well as accounts at all the top couture houses; but after infidelity, drink, cocaine, a car crash and the arrival of the Agnelli sisters, the affair ended. But the procession of men continued: Elie de Rothschild, Stavros Niarchos and a troupe of other wealthy lovers — “many, many, many,” as Pamela herself said later — who paid her enormous bills.

Although Purnell does her best to polish up her subject’s image by emphasizing how much Pamela did for her men in the way of decorating their villas, smoothing their rough edges and introducing them to the right people, it was a life of utter selfishness, culminating in the acquisition of another woman’s husband, the Broadway producer Leland Hayward, then flush with profits from The Sound of Music. With him, she lived her usual grand life, with an elegant Manhattan apartment and a country house. As one of Capote’s “Swans,” she made the mistake of confiding in the writer, and was featured as Lady Ina Coolbirth in his story “La Côte Basque, 1965.” After a long illness, and devotedly cared for by Pamela, Hayward died. Three months later, she married the now-widowed, 79-year-old Harriman.

The second half of the book is devoted to Pamela’s political life, initially working on behalf of her husband, then on her own account. Here there are some longueurs — I suspect because Purnell is so anxious to show that her subject was not just a “red-headed tart” (as one ambassador’s wife called her), that she adduces almost too much evidence to the contrary. That said, her research is impeccable, if sometimes repetitive. We learn how Pamela entertained, networked and gave highly successful fundraising dinners rejuvenating and enthusing those who saw no hope of a return from the 12-year wilderness of the Reagan-Bush presidencies. Pamela worked hard, with constant meetings, conversations with her European connections, suggestions and ideas, hiring top writers for the speeches and articles for which she was now being asked.

Finally, there came the reward. Clinton, whom she had spotted as a rising star early on, appointed her US Ambassador to France in 1993. Treating herself to the best facelift money could buy, she set off for Paris, where her past as a grande horizontale merely added glamour. So successful was her ambassadorship that when she died in 1997, President Chirac placed the Grand Cross of the Légion d’honneur on her flag-draped coffin. No other foreign female diplomat had ever received such an honor, and none had more deserved it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply