Henry III sat on the English throne for fifty-seven years. Among English monarchs, only George III, Victoria and the late Queen reigned for longer. But they only reigned. Henry’s problem was that he was expected to rule. In medieval England, the role of the king was critical. Public order collapsed without a functioning court system founded on the impartial authority of an active ruler. The scramble for office and influence at the centre quickly turned to civil war when the monarch allowed his vast patronage to be monopolized by a cabal.

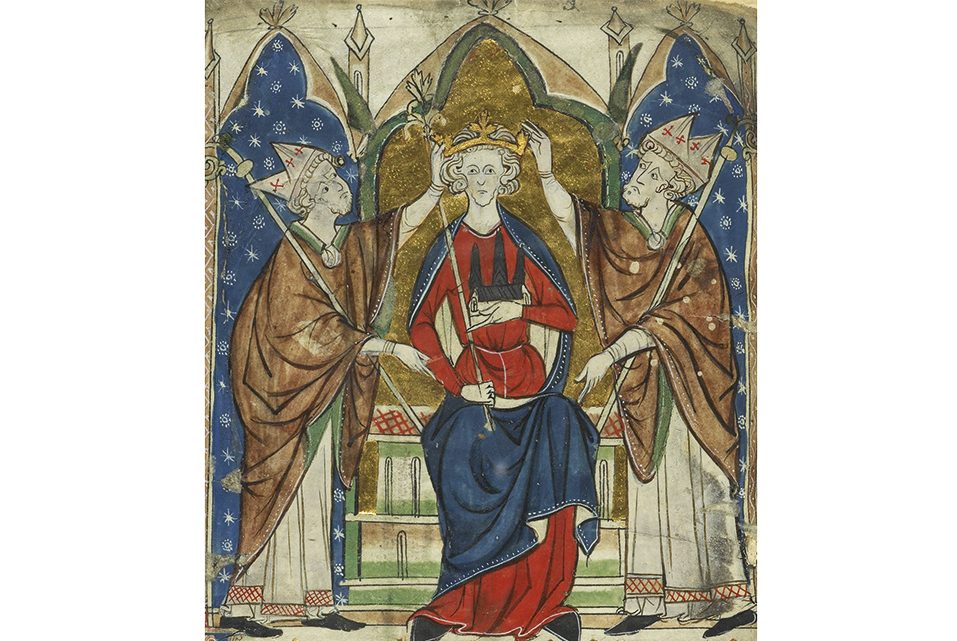

Contemporaries were satisfied that Henry III was a bad king. But what kind of bad king was he? Some kings were tyrants, who deserved to be deposed. Others were just useless, in which case their powers needed to be transferred to their wiser advisers. Henry was not a tyrant. He was kind and pious, a generous, well-meaning spirit. But he was useless. He allowed himself to be dominated by favorites and, worse, foreign favorites. He took a back seat behind the engines of power. Dante, that shrewd commentator of the next generation, thought him a simple fellow, il re della semplice vita, and assigned him to a corner of Purgatory reserved for neglectful rulers.

This is the second and concluding volume of David Carpenter’s magnificent biography of the forlorn king. His first volume recounted Henry’s difficult legacy. He came to the throne at the age of nine, without the long political apprenticeship that his predecessors had enjoyed. Like others in the same position (one thinks of Richard II and Henry VI), he lacked self-confidence and needed to surround himself with close friends and mentors. His early years were blighted by disastrous wars, in which most of the dynasty’s vast possession in France were lost. But despite these losses, Henry III never thought of his realm as an island. England was part of a continental polity which still included the great French principality of Aquitaine. His closest relatives and friends were French, Provençal or Savoyard. His younger brother became king of Germany. He measured himself against continental rulers such as Louis IX of France, at a time when much of the baronage, severed from its French roots, was becoming more insular. His half-baked scheme for conquering Sicily at the expense of English taxpayers proved to be his undoing. The Oxford Parliament of 1258 deprived him of most of his powers and placed him in lead reins pulled by a council nominated by his barons.

It is at this point that the present volume opens. The Provisions of Oxford, which were intended to return England to some kind of normality, in fact proved to be the prelude to seven years of continual political crisis and intermittent civil war. Henry recovered power in 1260, only to lose it again three years later. He cuts a sad figure in these years, buffeted by shifting coalitions of his subjects, alternately bullied and imprisoned, forced to appeal to the Pope and the king of France for support against his own people.

His eventual restoration was mainly the work of his wife, Eleanor of Provence, and his eldest son, the Lord Edward. The decisive battle, fought at Evesham in August 1265, was at once a triumph for his cause and a personal humiliation. While his son commanded the royalist army, the king himself was a prisoner in the ranks of the baronial rebels. His partisans did not recognize him behind his armor. They wounded and very nearly killed him. “I am Henry, the old king of England,” he cried out as they grabbed at him. “For the love of God do not hit me.”

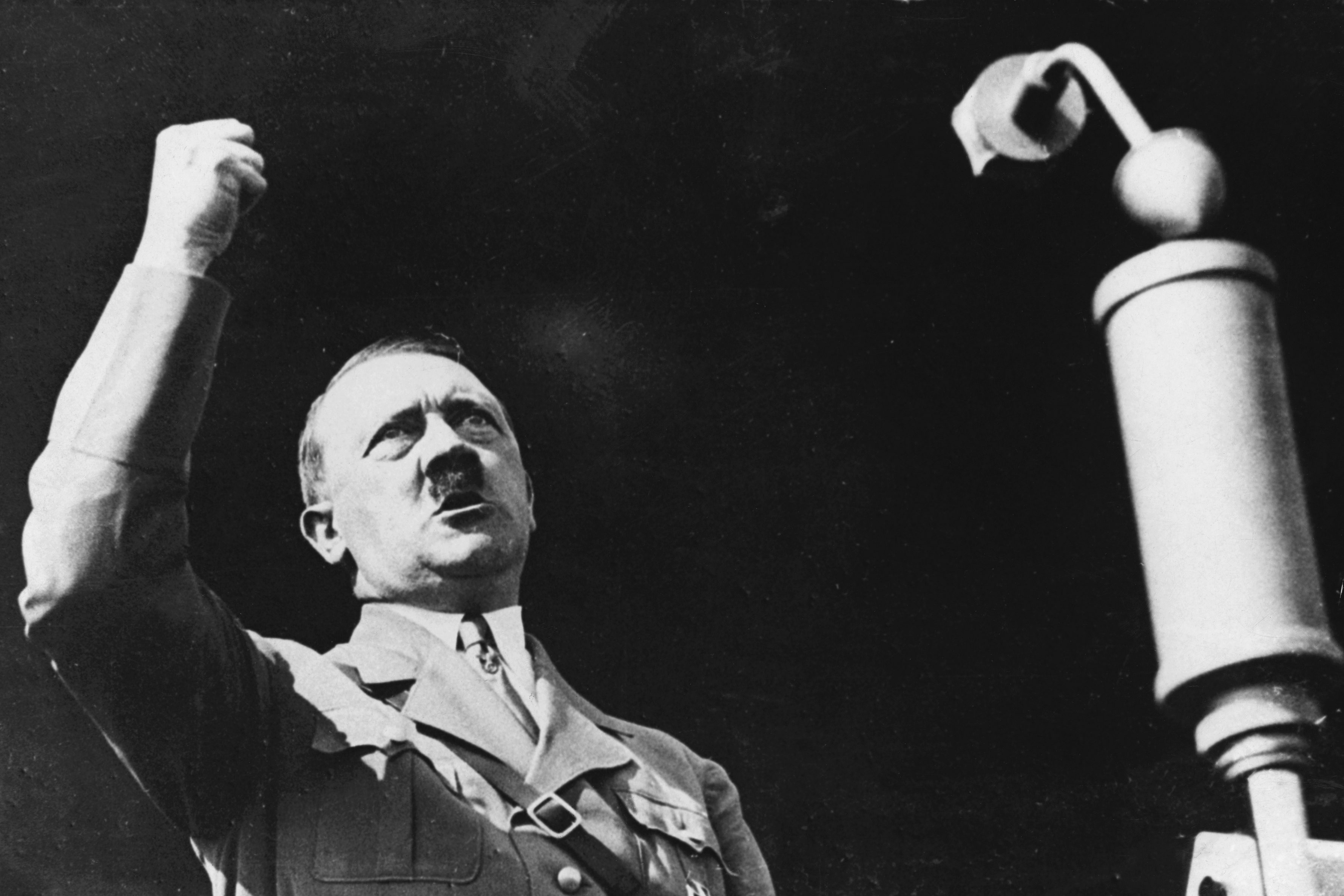

Most biographies are colored by hero-worship. Carpenter’s is no exception, but the hero is not Henry III. It is his foremost enemy, Simon de Montfort. He was an ambitious French carpetbagger who migrated to England, married the king’s sister and became Earl of Leicester. Throughout the years of turmoil and civil war, he was the animating spirit of the opposition to the king, an unyielding politician, a brilliant organizer and an outstanding propagandist. He built the disparate coalition of noblemen, churchmen and urban radicals which twice took power out of the king’s hands. The parliament of 1265, traditionally regarded as the first parliament because it was the first in which the towns were represented, was his work.

Simon de Montfort had a coherent political program, a vision of constitutional monarchy and a powerful idealism which won him a broader range of support than any other baronial leader of the Middle Ages. The Song of Lewes, which glorified his ideas, is one of the great political tracts of England’s history. The Lord Edward knew what he was doing when, at the battle of Evesham, he formed a special snatch squad to make for Simon and kill him. They did their grim work well. Yet Simon’s reputation and parts of his program survived. His tomb became a place of pilgrimage where miracles were reported for years after his death.

Carpenter’s account of a tragically inadequate king and a fascinating period of history is a superb work of scholarship, the fruit of a lifetime’s study of the subject. It is elegantly written, consistently shrewd and always good-humored. It completely supersedes Maurice Powicke’s Henry III and the Lord Edward, which held the field for seventy years. But it is also a very different kind of book. Powicke was a romantic; he bathed Henry III and his world in a nostalgic glow. Carpenter is more skeptical and realistic. The Middle Ages have left a legacy of writings, paintings and buildings of transcendent beauty. Westminster Abbey stands today as Henry III’s monument, as he would have wished. But it rose from the ground in an age of violence, greed, corruption and crude exploitation from which few emerge with credit.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.