Every circus needs a midget. This particular law of show business was established by the Victorians. It was P.T. Barnum who popularized the word ‘midget’. Harriet Beecher Stowe had used it in Uncle Tom’s Cabin to describe both children and a small adult, but it was Barnum, as great and merciless as master of the levers of sentiment as Dickens, who popularized the m-word when advertising the outsized talents of Colonel Tom Thumb, Commodore George Washington Nutt, and Lavinia Warren.

Commodore Nutt, who was not a naval officer, wore a naval uniform. He loved Lavinia Warren, whose real name was Mercy Lavinia Bump. But she married the bill-topping Tom Thumb, who was originally Charles Stratton. For the wedding, planned with more than usual cupidity by Barnum, Nutt was cast as the best man. This pained Nutt deeply, but Barnum had sold 5,000 tickets to the reception at $75 each. The show had to go on. The theater, having turned Nutt’s diminutive stature into a giant attraction, had become the stage of his nightmare.

The half-pint hedonist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was born in 1864, a year after Nutt’s heartbreak, to a pair of aristocratic first cousins. He emerged from this shallow gene pool with a cartoonish physiognomy, and an unknown genetic disorder that caused his legs to break in his early teens. They did not heal properly. In a plot whose tidy sentimentality could have been devised by Barnum or Dickens, Toulouse-Lautrec’s exclusion from ordinary physical activity sharpened his eye. The lightness and mobility denied to Toulouse-Lautrec by his faulty legs emerged from his hand.

Life had cast Toulouse-Lautrec for the circus, but he had family money as well as talent. As an artist, he was closer to Barnum than to Commodore Nutt. Toulouse-Lautrec and the Stars of Paris, now at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, shows the commercial artist as publicist, visionary, and ringmaster of the modern circus of celebrity. His stage was Montmartre, the district whose entire population seems to have spent its lives in the gutter, looking up at the talent on the stages of the cabarets. If ‘Les stars’ retain their uncanny immortality, it is because of Toulouse-Lautrec, who made us all the audience of his gorgeous and cruel freak show.

Familiarity breeds contempt, but also backstage intimacy. Toulouse-Lautrec was a commercial artist whose mass-produced posters were affixed to walls with brush and glue. Copies of the copies still proliferate across bourgeois kitchens and mock-Montmartre cafes, even though no one remembers who Jane Avril and Aristide Bruant were. It is easy to forget the quality of Toulouse-Lautrec’s line (shown here in a set of drawings from the collections of the Boston Public Library), his mastery of Japanese space, his assimilation of Degas and the new lithographic technology to the exigency of flogging items like Simpson’s patent bicycle chain. This device propelled the able-bodied male in pursuit of healthy leisure. Disabled and unhealthy — an alcoholic, he filled his cane with liquor — Toulouse-Lautrec was drawn to the damaged and the glamorous. Drink and syphilis finished him off at 37.

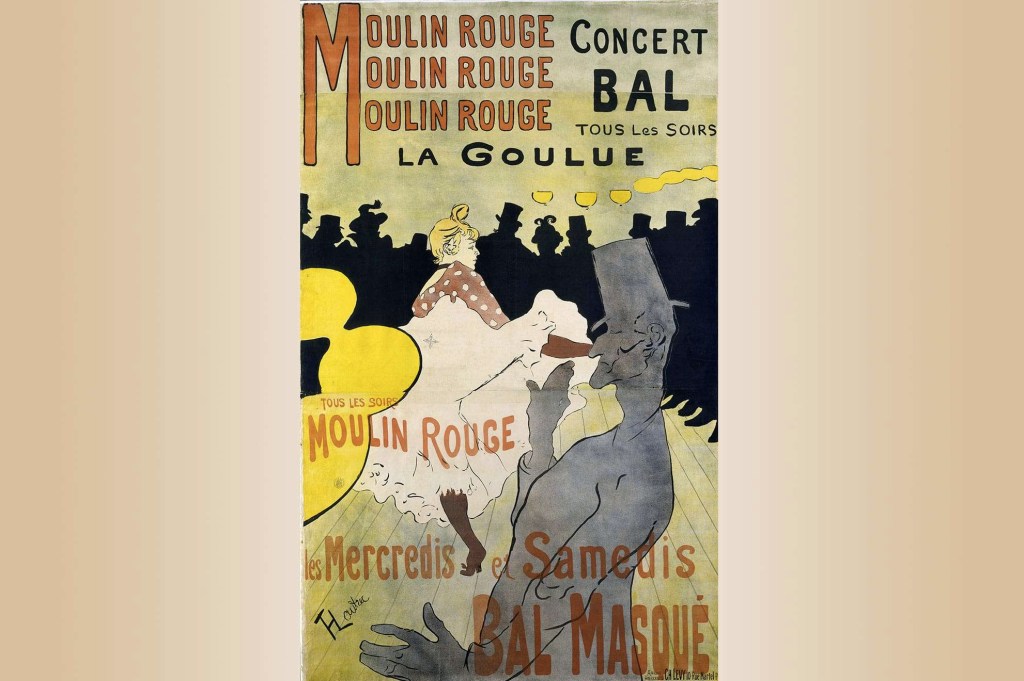

Mass production is also the business of the star performer, obliged to replicate the performance once more with what looks like feeling. Toulouse-Lautrec’s first poster for the Moulin Rouge, La Goulou (1891), anatomizes the business of show perfectly. Louise Weber, known as La Goulue, ‘The Glutton’, for her habit of finishing other people’s drinks, dances the chahut, a crude precursor to the Can-Can, her face blank and her leg in the air. In the foreground, the elongated dancer Valentin le Désossé, ‘The Boneless’, is seen in rubber-limbed, top-hatted profile. His right hand appears to be lifting up her leg.

Toulouse-Lautrec arranges the scene in three economical layers of silhouette. La Goulou is sandwiched between Le Désossé and, in the background, the black outlines of the audience. The viewer is the voyeur of the performance, watching the watchers. From our viewpoint, the audience are now the midgets, the performers the giants, and we are taller than Le Désossé. Or standing on a chair. For the elegance of Toulouse-Lautrec’s line retains an acidic, contemptuous force. When the famous Jane Avril extends her high-kicking foot on the stage at the Jardin de Paris, Toulouse-Lautrec pairs it with the well-turned scroll of the double bass whose neck is handled by the hack musician in the pit. The business of making a star shine is dark and dirty work.

May Belfort wore English-style baby-doll dresses and sang numbers rich in innuendo. In ‘Daddy Wouldn’t Buy Me A Bow-Wow’, Belfort meowed lines like ‘I’ve got a little cat, and I’m very fond of that / But I’d rather have a bow-wow-wow, bow-wow-wow.’ Toulouse-Lautrec, who noted that she was ‘a very pretty girl’, depicted her onstage at the Cabaret des Décadents, pouting in an infant’s dress and cap, and then offstage. The white pancake on Belfort’s face is tinged with Absinthe green, and her red lips are hard and unsmiling. All life is in the theater, but ‘the life’ empties out the actors. The highlights of this show are a series of brothel scenes, commissioned for private sale.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.