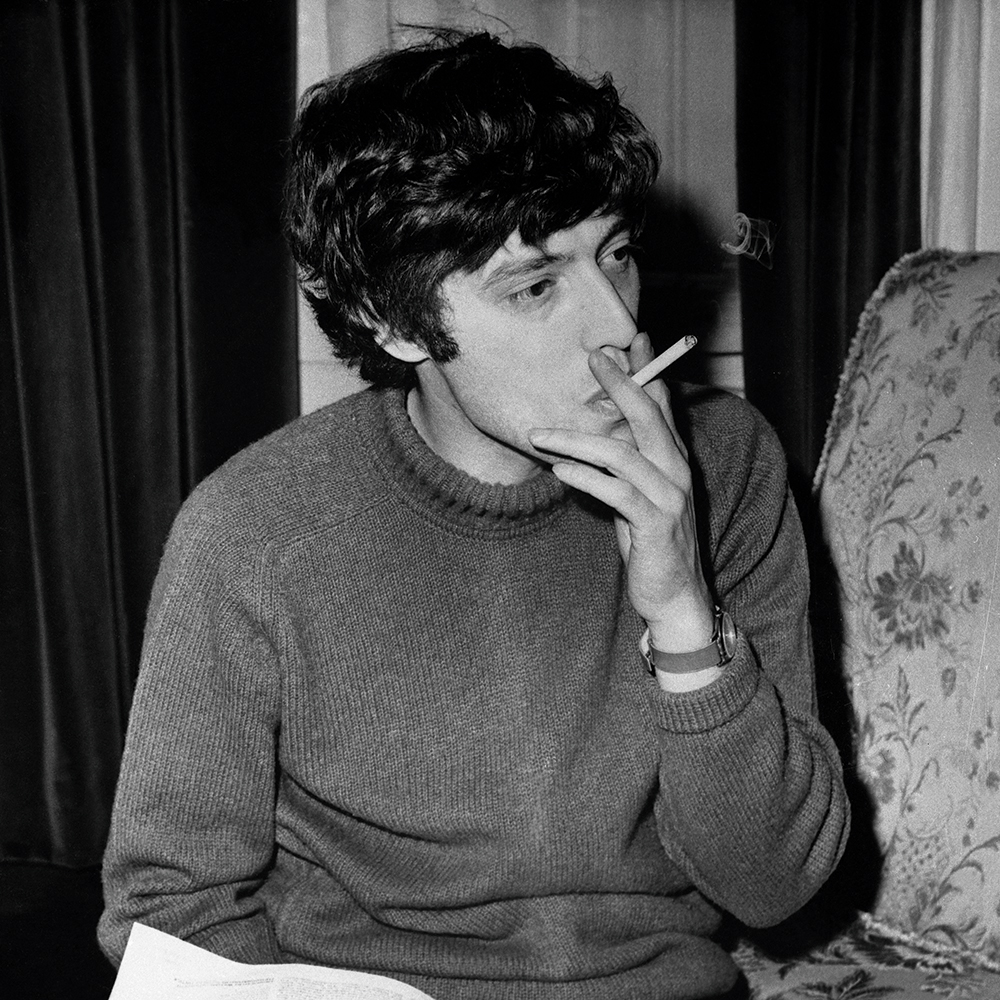

Many years ago, and well retired, I was working in my study at home when the phone rang and a voice said, “This is Tom Stoppard. David West put me onto you.” David was the professor of Latin at Newcastle University and it emerged that Tom used him when he had queries about Latin, but now had a question about the ancient Greeks. When he couldn’t answer it, David suggested that Tom should call me.

I felt a vast chasm of ignorance opening in front of me and have no memory of what the question was – but my reply must have satisfied him because he continued to throw the odd leg-break my way. To give some idea of his range of interests, on one occasion he became interested in the Greek perfect tense. Don’t ask me why, but that was at least something I could do.

In his play Rock ’n’ Roll, the passion and energy of the Lesbian poetess Sappho are used by the British classicist Eleanor as a parallel to the emotions aroused by rock music. We chatted around ancient and modern attitudes: Greek views of love as bittersweet, violent and unmanageable, and which can be controlled only by turning the experience into a dramatized, witty fantasy, often free of emotions – as against Catullus who put the pain back into the frame, exploring for the first time what love meant in sexual and non-sexual terms, and examining the mind-set of his beloved (Lesbia) as intensely as his own.

Infuriatingly, I missed a trick. There’s a wonderful image in a fragment of Sophocles which likened love to the “thrill of boys playing with fresh snow until their hands freeze, and they cannot wipe it off.” Tom said he would have loved to use it, but, alas, I had remembered it too late. But I did persuade him that the Sappho poem in the play was not about love but about envy. However, on the opening night it turned out to be about love after all. Repressing the desire to stand up and give the audience a brief lecture on the subject, I asked him what had gone wrong. “Nothing,” he replied. “The actors thought you were wrong and the actors are always right.”

At one of his summer parties, he told me rather gloomily of André Previn’s wish for him to produce a prose poem for Previn’s regular collaborator Renée Fleming to sing to orchestral accompaniment. Tom admitted he had doubts about the project because he’d never written a prose poem before, let alone one backed by a string quartet and piano.

Anyway, he had taken it on and would make its subject Penelope, the faithful wife of Odysseus, left at home for 20 years and besieged by suitors while he was returning home after fighting at Troy. Apart from Homer’s Odyssey, what should he read? Three or four hundred academic articles, most in German, flashed through my mind, but I said all he needed to do was to read Ovid’s brilliant take on the subject in his Heroides (“Heroic Women”), in which women from the grave reflect on their fate.

The result was, of course, a scintillating miniature – though we agreed that there was perhaps a little too much about Penelope’s family. (Tom’s desire for knowledge was omnivorous.) I felt that the only thing I could offer was to try it out privately on family and friends, without telling them who had written it. I hardly need to describe the reception. But Tom still had his doubts about the whole idea, as indeed did I. Even so, it went ahead at the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s annual Tanglewood Music Festival in 2019.

About a year had passed when I bumped into him at a literary festival. I asked him how Penelope had gone down and he made a face which indicated, “Not very well.” So I suggested to him that it would make a wonderful one-woman show – minus the music – and since Jimmy Mulville of Hat Trick Productions was about to become chairman of the charity Classics for All (of which Tom had been a patron) we might be able to persuade him to film it and premiere it in the UK, doing some good for the charity at the same time.

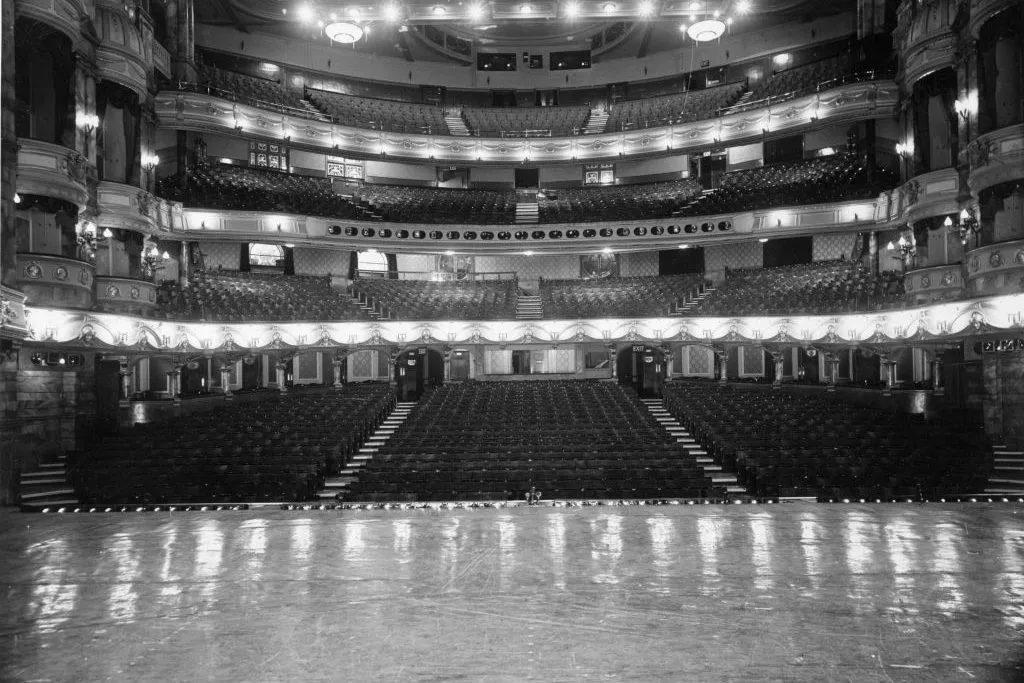

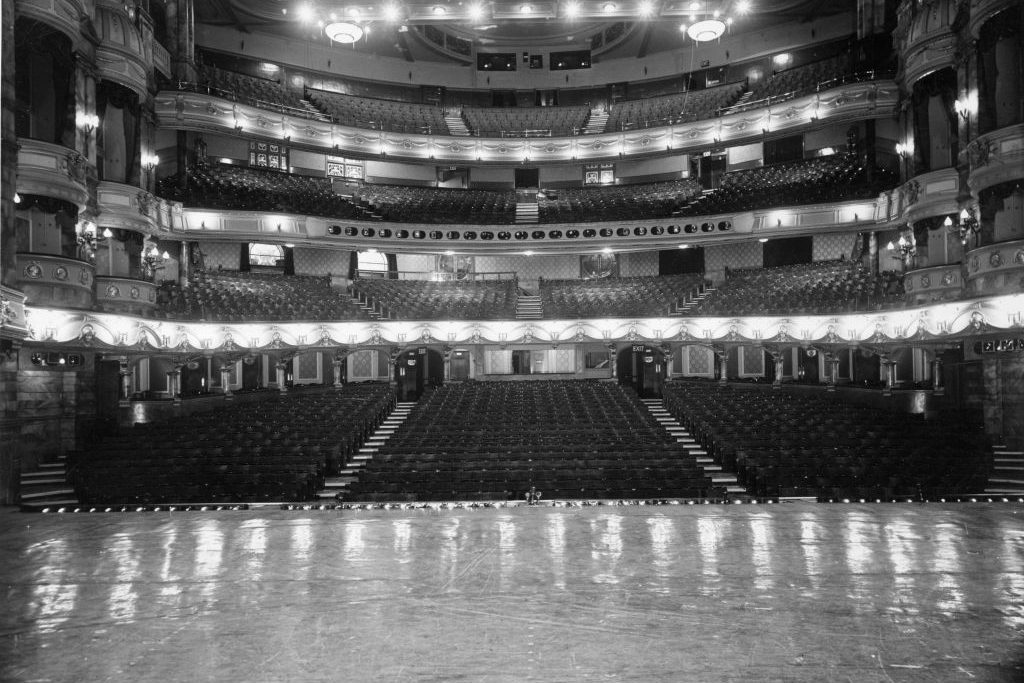

The deal was done and in November 2021 at Cazenove Capital in London it went ahead before a selected audience, with Hattie Morahan playing Penelope. The care and attention that Stoppard showed during the preparations were admirable, He spent a long time with Hattie, who had been drafted in at short notice – and the show was prefaced with a discussion about Penelope between Tom, the BBC’s Martha Kearney (an Oxford classics graduate), and the academic Dr. Emma Greensmith.

It is worth quoting from the classical scholar John Godwin’s review, which makes it abundantly clear that we are in Stoppardian territory:

Penelope looks back from “the dark plains of Asphodel” over her family history, going over her early life and subsequent marriage to Odysseus. She has some sharp words for Helen (“round-heeled runaway Helen of the bee-sting lips and who-me? eyes, not known for her weaving”) and a wonderful range of avian metaphors for the impregnation of Leda, mother of Helen who was “conceived in a wing-beat” when Zeus “swanned past Leda’s defenses and begat the slut.”

S. has managed something which may look easy but which is in fact almost impossible to achieve: he has recreated the inner emotions of Homer’s Penelope in such a way as to be credible both in ancient and in modern terms, using language which manages to avoid the Scylla of archaism and the Charybdis of pastiche.

Hattie’s superb portrayal did Penelope full justice.

Penelope is a masterpiece of Stoppardian cunning. He makes her quite the match of her husband in a language whose invention and precision surely drew a nod of approval from western literature’s First Father.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 22, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply