In 2009, cinema audiences were faced with a choice between two talking-fox pictures. The first, most obviously user-friendly option was Wes Anderson’s Roald Dahl adaptation Fantastic Mr. Fox, with the eponymous reynard voiced by none other than George Clooney. If your tastes verged on the darker and more perverse, the Danish director Lars von Trier had a treat in store for you with his controversy-laden psychodrama Antichrist. In one key moment, the male protagonist played by Willem Dafoe is approached by a mangy-looking fox — voiced, uncredited, by Dafoe himself — that declares, in maniacal bass tones, “Chaos reigns!” You wouldn’t get that with George Clooney.

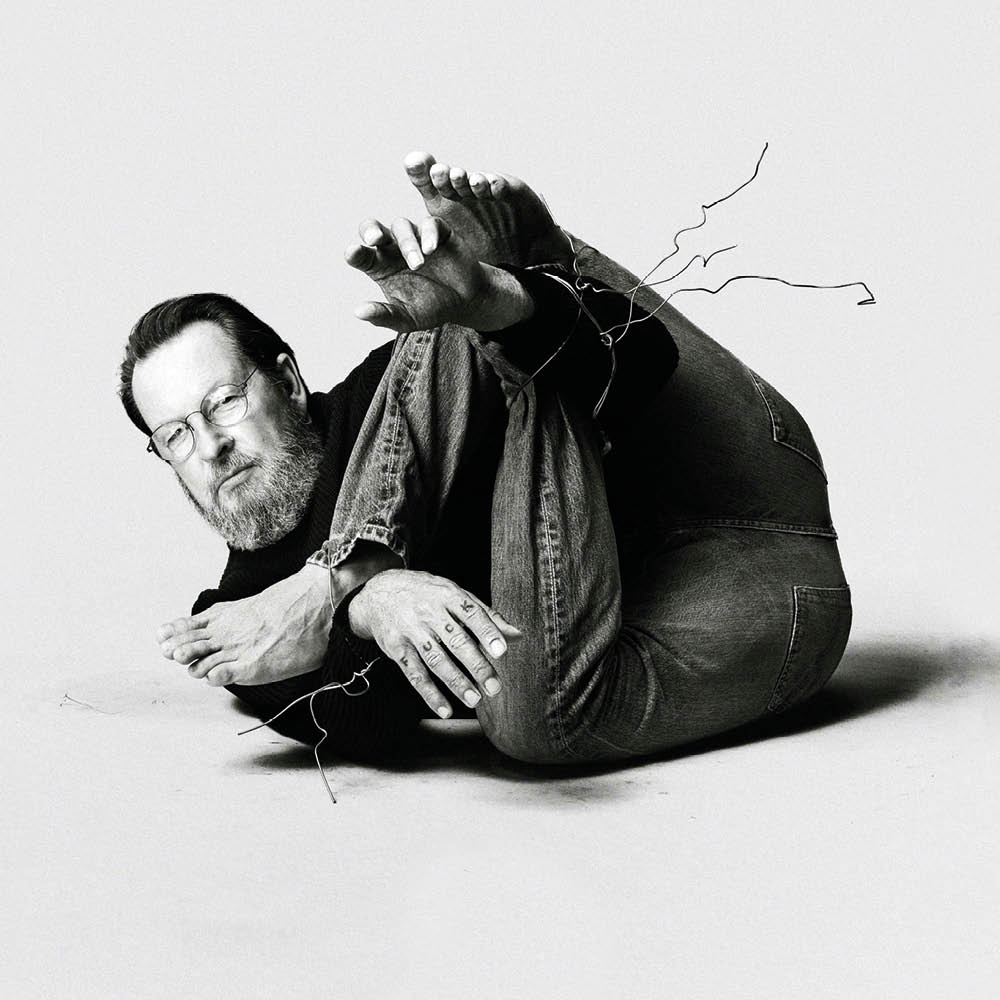

Von Trier may now be sixty-eight years old, but over a forty-year career that began with 1984’s nearly incomprehensible but visually stunning serial-killer drama The Element of Crime, he has spent his time pushing the boundaries of cinema to the extreme. For every viewer who praises his work as challenging, unique and experimental there will be likely twice as many who denigrate it as repellent “shock art.” Few directors are more divisive or geschmackssache. Von Trier predictably revels in this; as he once remarked, “Somebody has to hate the movie. That’s important.” Or, as he put it more bluntly elsewhere, “A film should be like a rock in the shoe.”

Few would turn up at the local picture house for the new von Trier and expect an anodyne romp. He has made everything from the coldly Brechtian Dogville and Manderlay, in which he dispenses with sets and props altogether to create coruscating satires on Thirties America, to his deeply uncompromising Nymphomaniac which teeters between graphic, hypersexual realism and religious mysticism. Then there are the films that attracted critical praise — such as his psychosexual odyssey Breaking the Waves and perhaps his greatest work, the visually stunning apocalyptic drama Melancholia — and those that were treated with a mixture of ridicule and contempt.

Few would suggest that his 2018 picture, The House That Jack Built, was his finest work. A rhapsodic journey into a deeply disturbed mind, with metaphysical and Virgilian elements, it has a unique capacity to shock. At its premiere at Cannes, around a hundred people left the theater in disgust. It is not hard to understand why: in one scene a duckling is disfigured with wirecutters, in another a single mother and her children are mercilessly shot down by a serial killer. Von Trier recounted the walkouts gleefully: “There were different seats that were going ‘boom!’ Every time a new murder came it was ‘boom-boom-boom-boom-boom!’”

They should have known what to expect. Von Trier’s work is a masterclass in cinematic vexation, crafted to make viewers squirm, recoil and examine the origins of their discomfort. His reputation — he might politely be described as an arch-feather-ruffler, less politely as an incendiary exhibitionist — has its origins in his debut English-language feature, The Element of Crime, which exhibits in microcosm all the traits that mark von Trier out as an era-defining director. In his eyes, evil is omnipresent in the world. Far better, he thinks, to look it directly in the face.

Admittedly, this makes von Trier’s movies a lot to swallow both visually and emotionally. Their “morals,” if they can be called that, can be hard to decipher. Yet only the plain-minded seek ethical guidance from cinema; its aesthetic wonders are just as necessary, too. This might make them seem too ideological, too abominable, or too art-house to appeal to the average cinemagoer. But just as his films gaze on the face of wickedness, many of them can be profound and funny in equal measure, their dark humor manifesting in bizarre and grotesque ways. Such moments are quintessentially von Trier: unsettling, surreal and perversely facetious. After two and a half hours of warped immorality in The House That Jack Built, ending it with the depraved protagonist at the entrance of Hell, scrambling across a chasm toward the gates of Heaven only to slip and fall, is slapstick gold that Chaplin and Keaton would have applauded.

With the Hollywood landscape increasingly dominated by trigger warnings and safety-first storytelling, von Trier remains a necessary dissenting voice, reminding us that it is healthy to both wince and wink in the face of pain and suffering. You won- der, though, what he would come up with if tasked with producing a mainstream blockbuster like Deadpool or, better yet, It Ends With Us. A von Trierian antihero might boast healing powers but they’d probably be enacted via accelerated Freudian psychoanalysis and Plethora, Maine’s poor old Lily Bloom might end up recast, not as a victim of abuse but as a latex-encased dominatrix.

Von Trier had a Colleen Hoover moment himself recently when he posted a rather peculiar Instagram ad searching for a new “girlfriend and muse.” Because he is generous enough to tempt potential partners with his wares before they meet him, von Trier wanted to make a “few things clear”: “I am 67 years old. I have Parkinson’s, OCD and at the moment controlled alcoholism.” “Despite all the whining,” though, he insists that “on a good day, in the right company, I can be quite a charming partner.”

Many women, you suspect, would steer clear upon hearing of the multiple charges of misogyny against the director. Certainly, his sets have been plagued by stories of coercion and conflict: on the set of Dancer in the Dark — a musical, ladies and gentlemen, that ends with the protagonist executed! — von Trier’s antics drove the equally volatile singer Björk to tear apart her blouse and eat it in front of him in protest. But for von Trier, such accusations are like water off a (mutilated) duck’s back. When he made Antichrist, he even hired a “misogyny consultant” to “furnish ‘proof’” of the satanic feminine throughout history. She was duly acknowledged when the credits rolled.

Von Trier, in fact, has a guilty little secret; he is a card-carrying feminist masquerading as a provocative misogynist. He has consistently written complex and interesting roles for women, even if their characters are subjected to appalling sexual and physical assault. In Breaking the Waves, the divine psychosis which tricks Bess McNeil into performing humiliating sex acts to appease God is not a black and white issue of violation. Played expertly by a young Emily Watson in her film debut, Bess’s is a story of enduring human longing and sadness. As none other than Martin Scorsese — himself no slouch when it comes to exploring the divine on screen — put it, Breaking the Waves is “a genuinely spiritual movie that asks ‘what is love and what is compassion?’” When it comes to knotty female storylines, Bess’s constitutes a far more compelling character analysis than, say, the entire narrative of Barbie.

Von Trier’s magnum opus, Melancholia, also puts female narratives front and center. Here two extraordinary actresses, Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg, play sisters who must come to terms with their wildly differing responses to the end of the world. The film is unexpectedly ultra-stylized (von Trier’s movies are more often on the drab side). Viewers are treated to haunting slow-motion visuals, artistic nods to the likes of Millais and Bruegel and a Wagnerian soundtrack. Emotionally suffocating yet visually sumptuous, Melancholia comes close to operatic genius. Part of the reason it is so good is because it is so beautiful, a Barry Lyndon for the apocalypse. Appropriately, it is all bang and no whimper.

Fittingly von Trier’s most glorious and extravagant film invited the largest controversy of his career. His inimitable brand of ego-comedy landed him in boiling water at the film’s 2011 Cannes premiere. After making an ill-judged Nazi joke, von Trier received a seven-year ban from the festival — he may have concluded by now that declaring “I understand Hitler” isn’t going to go down well anywhere, ever.

But to understand von Trier, we must accept him the way he sees himself: as both a dastardly provocateur-auteur and a deeply flawed human who can laugh — darkly — in the face of evil. You can understand — forgive, even — Von Trier’s clumsiness, his propensity to ram his foot in his mouth, when you recognize that the only thing he is reverent toward is irreverence. The fact that this might make him persona non grata is a boon — it’s all part of the performance.

Most of von Trier’s films implicitly refer to the great line in The Tempest, “Hell is empty, and all the devils are here.” Von Trier is our great demonic ringmaster, eliciting wild laughter in the face of grief, and we should be grateful to him for his rigor and conviction. His art has never just been shock for shock’s sake. Underneath all the muck, the dismembering, the gore and psychological torment, there are many more moments that linger in the memory for ever, awestruck: Dunst traipsing across a golf course in her white wedding dress; the ecstatic, vertiginous whiplash induced by Dancer in the Dark’s thrilling Bjork-scored musical sequences; the eerie woodland vistas in Antichrist; and the elegiac heavenly bells at the end of Breaking the Waves.

Over the last forty years, von Trier has constructed an oeuvre of unique ambivalence. Its reigning deities are beauty commingled with monstrosity, horror commingled with hilarity. Philosophical directors are a rare breed these days, but they are desperately needed — it would be something to see von Trier direct a retelling of the Old Testament. With its mix of brutality, moral tests and acts of judgment, the result would be a career-defining spectacle. Whether you’re repelled or enticed, one thing is for certain: while you weren’t looking, the trickster would be slipping a rock into your shoe.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply