It’s hard not to feel slightly odd when standing in front of a Milton Avery painting. Take his 1943 work Hors d’Oeuvres as an example. The painting — currently on show at London’s Royal Academy’s exhibition, Milton Avery: American Colorist — is large, at nearly a meter across, and the background is what appears to be a coastal landscape, with a greenish sea and the curve of a bay appearing in the upper right-hand corner. In the foreground of the painting is a cream table and on it, a blue platter of food: the “hors d’oeuvres” of the work’s title.

So far, it might be hard to understand what is so disconcerting about this painting. It isn’t Avery’s subject which sets my stomach on edge, it’s his composition: the table is clearly in the foreground, but its diagonal position and perspective suggests the opposite of depth and volume — an unending, discombobulating flatness. Despite the appearance of space, foreground, and background, the painting on the wall is relentlessly — and brilliantly — one-dimensional.

Hors d’Oeuvres was painted in 1943: Milton Avery, at this point, had been painting for some thirty years and had begun to achieve recognition and fame for his work. He was not formally trained as an artist — he had worked in factories while completing night classes in commercial lettering and eventually painting — but had entered an artistic milieu: he was married to fellow artist Sally Michel, was friends with the much younger artist Mark Rothko, and had been represented by New York’s Valentine Gallery since 1935. His work began in the American Impressionist style (influenced by the likes of John Henry Twachtman and Ernest Lawson) but had soon moved on from their style of naturalistic colors painted in loose, open brushstrokes.

By the 1930s, Avery was still painting landscapes, but there was something different about his style. The aptly titled Moody Landscape (1930) is suffused with darkness, bold black outlines, and a thick impasto gloomy sky. But it is in his works painted in the later ‘30s where the change becomes clear. Both the watercolor Fox River Village (1938) and the oil painting Fishing Village (1939) play with perspective, depth, and viewpoint. In Fox River Village, houses become little more than dotted white squares — simultaneously proportional to the landscape that surrounds them, and also deeply odd. From the viewer’s position, it appears they should be seen from a flattened bird’s eye view. Instead, we have dimensional clusters and groups: just as the painting draws you into its space, it forces you out again in its improbability.

In Fishing Village, this effect is even clearer: Avery has painted a cliff and hilltop next to a grey beach with driftwood and other detritus on it. A path from the beach leads the viewer’s eye up to the cliff, where there is a small group of houses. The only problem is, the path is at such an improbable angle, and the hill so unnaturally curved, that any sense of three-dimensional shape immediately bends and buckles.

This is not the fault of faulty draughtsmanship: Avery well knew how to draw a cliff. Instead, he is consciously playing with space and perception — this is landscape painting, but not as we know it.

In his later years, Avery would be renowned for his use of color: abstracted blocks of brightness and canvases filled with opposing hues. In 1952, the art teacher Hans Hofmann went as far as to say that, “Avery was one of the first to understand color as a creative means.”

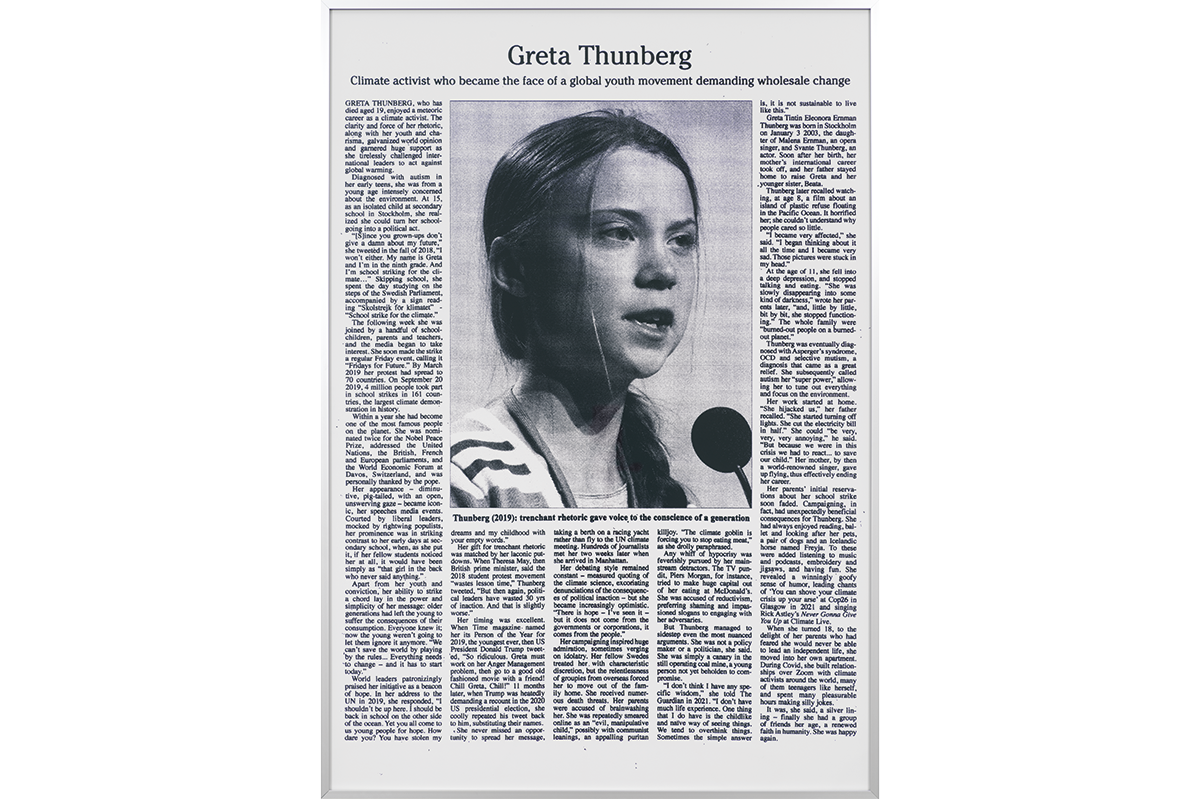

Paintings like March in Babushka (1944) and Two Figures at Desk (1944) demonstrate an absolute mastery of color. In its precision, and with a style that is more evocative of cut-out paper than it is thick oil paint, Avery’s color becomes form itself. This is clearest in Seated Girl With a Dog (1944): the girl’s face and body, the room’s shadow and form, the dog’s limp shape — all are economically created with blocks of color.

Milton Avery, Seated Girl with Dog, 1944

Color is, now, what Avery is known for, and the exhibition ends with his dramatic later landscapes: the Rothko-esque blocks of paint Blue Sea, Red Sky (1958) or the brilliantly minimal Black Sea (1959). But here, as with his earlier works, there is a continual sense that Avery is playing with space. In Beach Blankets (1960), it should not be possible for the human eye to see both the un-foreshortened blankets (as if from above) and the sea, a black-blue line as if seen from a distance. But, in Avery’s world — where form is color, and color is form — it is possible.

Avery’s work exists on the boundary of abstraction and realism — he is often described as the link between Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism. But his work doesn’t remain static on this boundary. With every fresh look, each painting pulls the viewer closer to understanding it, seeing it, and entering its space — all before pushing us out again, and forcing us to puzzle at it from beyond the frame.