As she recalls a decade of infamy, Maria Alyokhina wanders one of the many anonymous apartments she has lived in since escaping Russia six months ago. “We didn’t expect a criminal case, we didn’t expect imprisonment, we didn’t expect international attention. We didn’t expect how many people would support Pussy Riot, would go to the street in balaclavas. We could never have predicted that.”

Alyokhina and Pussy Riot, a loose feminist collective who perform in brightly colored balaclavas, came to international attention in February 2012 with their “punk prayer,” a guerrilla music performance in Moscow’s orthodox Cathedral of Christ the Savior.

Plugging in an electric guitar to an amp, they moshed about the nave, evading security guards and shocked nuns as they belched out the chorus: “Virgin Mary, Mother of God, banish Putin/ Banish Putin, Banish Putin!” For this Alyokhina and her bandmate, Nadya Tolokonnikova, were imprisoned for two years, staging three hunger strikes to highlight the torturous conditions they were subjected to.

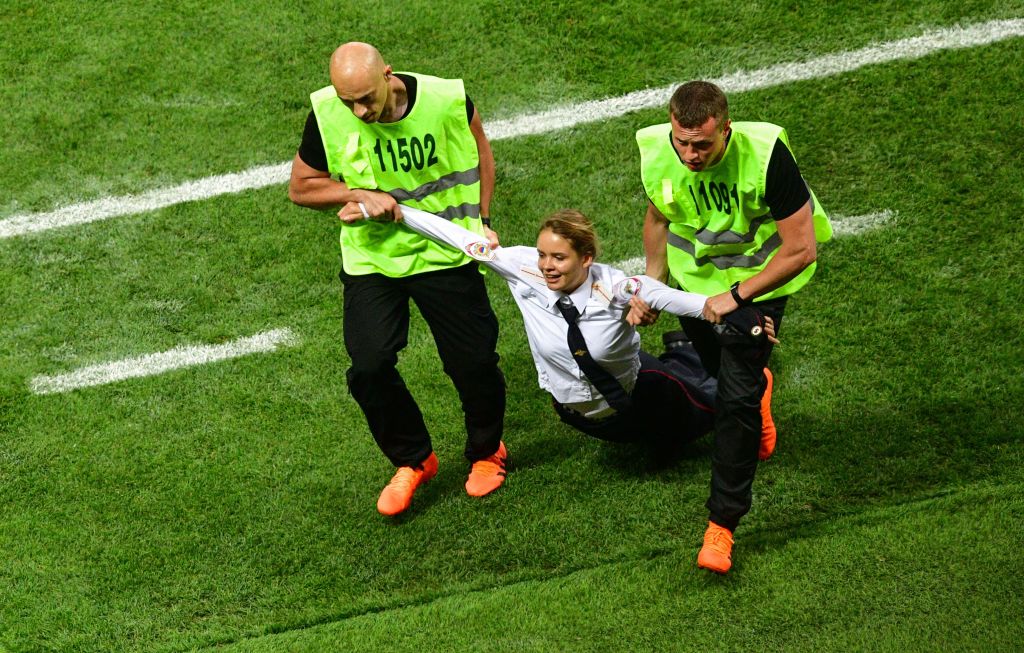

They have stayed in the limelight since, staging stunts similarly designed to troll the Putin regime, ranging from hanging rainbow flags outside government buildings on the president’s birthday, to a pitch invasion dressed as policewomen during Russia’s hosting of the World Cup in 2018. And despite further arrests, imprisonments, beatings and a colossal amount of intimidation, Alyokhina refused to leave Russia.

She says the invasion of Ukraine changed matters. “They created several new criminal articles to provide censorship for the invasion… it’s impossible to do or say anything.” As Russian tanks rolled over the border, a sign was posted on her apartment door accusing her of being a traitor, and the authorities charged her with a newly created crime, “propaganda of Nazi symbolism,” relating to a 2015 social media post where swastikas accompanied an image of three women in hijabs.

In May, under house arrest, she removed a security tag and escaped before she was sentenced to a penal colony, sneaking out of a friend’s apartment disguised as a food courier. It took her three attempts to cross into Belarus. She was successful only on the third try, having secured a travel document from an EU country — she refuses to say which one. The courier uniform was a nice touch, I say. “If you deal with Russia’s political police for a long time, then to make jokes at their expense is a way to survive. From the outside they are this all-powerful edifice of evil, but from the inside it’s these stupid, corrupted, drunk people, half of whom hate what they are doing. To be able to troll them, even a little bit, brings a little bit of happiness.” After three days crossing Russian-allied Belarus, Alyokhina at last reached safety in Lithuania, eventually ending up in Iceland from where she is speaking to me.

“I want to go back to Russia at some point. It’s my country. It’s what I’ve been fighting for all this time, but for now I’m focusing on Ukraine.”

This focus includes a European tour raising money for hospitals in the invaded country and an exhibition at Kling & Bang, a non-profit gallery in Reykjavik, titled Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia, which surveys the collective’s ten years of Putin-baiting. All those actions, Alyokhina says, were intended to convey a message that she thinks is only now being understood by the West.

“There were a lot of repressive steps during these ten years: murders, poisoning, imprisonment, but somehow this wasn’t a concern for the world. Western politicians and businesses continued to work with the Russian state, with Putin himself, inviting him to summits and accepting him like he is the president. And yet the elections aren’t elections, so the president is not a president, Russia has not been a democracy for a long time.

“The politicians were not naive, they were just bought by Putin’s capital. It was cynical and hypocritical. Germany and Italy are not the only examples. The media didn’t cover what was happening there either. There was no real light shone on the systematic torture in police stations and prisons. Only the blood of a totally innocent country caused Europe to wake up and introduce proper sanctions.”

Is there a danger that their way of protesting feeds Putin’s propaganda of a degenerate West that only he can protect Russia from? A new video made for the show features one of the band lifting up a baggy dress and urinating on a portrait of the president. A frown appears and she cuts my question down with a curt mockery perhaps honed from many hours of interrogation by state security. “This is a very strange question. They censor any difference, any artistic difference, any political difference. And that’s it. You can draw any person as evil if you have a huge propaganda machine working for you, you can take the most innocent person, an angel, and make a demon.

“It is about showing that Russia can’t just be represented by Kremlin assholes. That we also exist and that we fight. We don’t have weapons, we don’t have tanks, but we have passion to fight this terrorist state.”

Alyokhina’s questioning spirit came early. When asked to write an essay at school glorifying Russia’s victory in World War Two she instead handed in a screed pointing out that Stalin was responsible for at least as many deaths as Hitler. She refused to take cookery classes while the boys in her class did woodwork and, on leaving compulsory education, she initially eschewed university in favor of traveling through southern Russia with a backpack.

It was learning that a forest in the Krasnodar region in which she had camped during that trip was in danger of being logged that catalyzed her more serious activism. “It upset me,” she says. “I started collecting signatures, then going to small rallies, then bigger rallies, becoming an ecological activist.” The music, which has softened over the years from raw shouty punk to the current more auto-tuned pop, came later. “The people with whom I was protesting were different from the friends I had at university — people who were into poetry and the arts — and I want to mix those activities.”

The Reykjavik exhibition is more a museological documentation of previous protests than an art show per se (though they mocked up a Russian prison cell). But what becomes clear is the group is working in a lineage of the Fluxus movement, where action took precedence over finished product. And while Pussy Riot sit comfortably in the angry and mad world of more recent Russian performance art — be it anarchic artist group Voina throwing live cats over a McDonald’s or Petr Pavlensky nailing his scrotum to the cobblestones outside Lenin’s tomb — Pussy Riot clearly love pop culture too, harnessing sex appeal and catchy hooks for radical means. A recent single is all Katy Perry-tinged tempo changes and computer software beats but contains the sample lyric: “I loathe and detest you/ Utterly abhor you/ I wish I was around to tell your mother to abort you.”

Her own religious faith gave her initial reservations about the 2012 cathedral performance. When I ask her about it she involuntarily reaches for a pendant around her neck. “We never wanted to hurt the feelings of any believers,” she says firmly, explaining the performance was a protest against the politicization of the church. What about her family? Her son, whom she has recently moved out of Russia to avoid the risk of being drafted, was young at the time. “If I feel this fear, I just continue to do what I think is right.”

She says, however, it was not the ensuing imprisonment that was the defining moment of her life, but the response to a far more innocuous 2014 action where the band attempted to perform outside the Sochi Winter Olympic stadium. “We did an action titled ‘Putin Will Teach You To Love the Motherland.’” The response was swift and brutal with videos online showing Cossack militia using horse whips on the women as plain-clothed state security stood by. “I realized then that this was not the Russia I knew two years before, it had become a different place.” How so? “After Crimea was annexed there was very little reaction from the West. There were very few sanctions. Those US sanctions that were put in place, like weapons embargoes, were undermined by Germany, Italy and France. That allowed systematic physical violence to become part of everyday life.”

Surely, though, she can’t lay the blame entirely on the international community? “Forget the idea that 80 percent of Russians support the war. It’s just propaganda,” she says. “It is not possible to create any expression against the war though. To overcome this terrible situation is an international problem, not a domestic one.”

Her interventionist stance puts her at odds with many of the left outside Russia, those who might well share her views on other subjects such LGBT rights, feminism and the environment. “I have a question for the people who say that they are afraid of a third world war. If Putin’s state wins this war, what do they think will happen next? It’s very obvious from history what will happen next. More countries will be attacked, and then there really will be a third world war.”

I ask her what she hopes to achieve from an exhibition in a safe country like Iceland. She shakes her head at my naivity and says that as much as she is in a battle for her own homeland, its slide into autocracy should be a warning for those abroad too. “Russia of course has a very long and complicated history, but if people stop the fight, what happened there can happen anywhere. The situation here didn’t come about in a single moment but there was a road to this hell. The purpose of doing this show is to help people, wherever they are from, recognize the beginnings of repression when they start.”

Velvet Terrorism — Pussy Riot’s Russia is at Kling & Bang, Reykjavik, until January 15, 2023. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.