“Every single song is like a road map to what that relationship stood for, with little markers that maybe everyone won’t know, but there are things that were little nuances of the relationship, little hints,” Taylor Swift told Yahoo! Music in 2010.

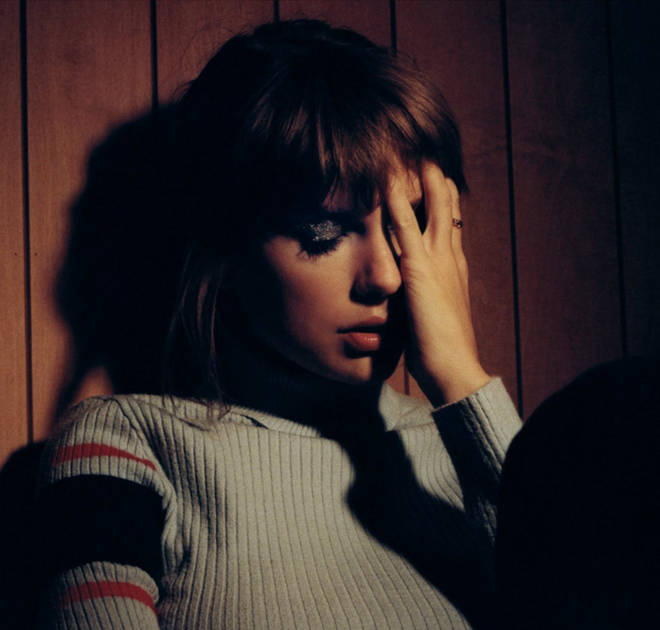

A decade of songwriting turned those “little hints” into complicated numerology, a scarf metaphor at the centerpiece of her canon, coded song titles, storytelling scattered with cardigan sweaters, Shakespeare references, faded blue jeans, true crime, YA tropes (e.g., witches, cats, prom dresses, teen love triangles and evil alter-egos) and glitter-glue covered diary pages — sealed with red lips.

Taylor Swift was fifteen when she began incorporating easter eggs and (wink-wink) secret messages into her work. She announced on The Tonight Show last year:

I wanted to do something that incentivized fans to read the lyrics…and look, I think that it’s perfectly reasonable for people to be normal music fans and to have a normal relationship to music, but if you wanna go down a rabbit hole with us, come along, the water’s great, jump in, we’re all mad here.

But there’s no such thing as a “normal” Swiftie; though there is a minority who want “Cardigan” to be influenced by Sally Rooney’s Normal People (let’s not go there). Most Swifties are deliciously unhinged.

“Taylor Swift fandom is Q-Anon for people who were a pleasure to have in class,” tweeted @cdiersing, which was punctuated by a top-tier reply: “Cute Anon?”

The “Cute Anon” conspiracy theorists of Swifties are divided into several subgroups. The most influential is “Gaylor,” a rabid group of fans that advances the theory that Taylor Swift is gay, that she’s coding her song lyrics (and social media posts) to quietly reveal this. One theory is that she’s closeted because of her more “conservative” country music roots. Taylor Swift remained private about her political affiliation for most of her career, opening herself up to close readings from the alt-right claiming her as their “Aryan Goddess,” which she quickly extinguished.

Taylor’s made only the vaguest attempts to put the Gaylor rumors to bed by saying LGBTQ is a “community that I’m not a part of.” She seems to not be able to resist fans obsessing over the mysteries of her life. To completely dispel Gaylor would also be poor storytelling.

There are numerous examples of Taylor using symbols and lyrics to keep Gaylor alive. The latest example is the lead single off Midnights, titled “Lavender Haze” (lavender is a known symbol of gay pride). This is a superficial and exaggerated close reading, but Taylor has never protested queer readings of her work. By allowing queer readings of her oeuvre, she’s building tension with a ticking clock that keeps her obsessed reader glued to the page until the big reveal. Will she come out of the closet?

“I’ve trained them [Swifties] to be that way,” she told EW in 2019, describing how she conditioned her fans to look for patterns that may (or may not exist) in her storytelling.

M.J. Corey, a pop scholar who studies the Kardashians under the moniker “Kardashian Kolloquium”, wrote in the New Yorker that Kim Kardashian uses superhero motifs to establish her ubiquity in the world. Taylor uses literary motifs to inspire an army of readers to help build her universe of Swifites, who are faithful translators of her scarlet-colored memoir, where a protagonist crashes a former lover’s wedding (Speak Now); composes Jake Gyllenhaal autofiction on “All Too While”; rips off her cute prom dress on Folkore; references Jane Eyre and The Sun Also Rises; turns emotional abuse into a story arc on Midnights, where she documents everything from an eating disorder to John Mayer robbing her of her innocence, a theme she explores often.

If there is an ongoing antagonist in her work, it’s John Mayer, who is referenced on the fifth track in Speak Now — “Dear John,” where Taylor is the girl in a dress, crying all the way home, planning her literary revenge with Swiftian wordplay that is designed for close reading. Taylor wrote him into a song again on her latest album, Midnights.

Fans often treat albums like the next edition of a “karma is real” series, a reminder that Taylor Swift likes to write revenge-themed stories that Swifties are conditioned to treat like “choose your own adventure” on “SwiftTok” and Twitter. “Revenge Swifties,” as they’re known, view Kanye West, Katy Perry, John Mayer, and Big Machine’s Scooter Braun as names on the list referenced in her song “Look What You Made Me Do.”

Karma for John Mayer in this case is found in Taylor’s red-penned numerology (a key feature of her storytelling). For example, track nineteen on Midnights is about John Mayer. Taylor Swift was nineteen when dated Mayer, who was thirty-two. Taylor is now thirty-two. Coincidence? Nothing she does is a coincidence; every detail is handled with meticulous care, like she’s outlining a fantasy saga with its own mythology and language. Numerology not only gamifies her work, it turns every lyric into a Dan Brown novel or detective story close reading.

Numerology for Swifties is another part of the secret language they use to separate themselves from normal music fans. It creates a connection between the writer and her fans, participating in the creative and consumption process.

Everything Taylor’s done since she was fifteen is purposeful, plotted and builds suspense towards big reveals, like her secret sexual identity or her next great revenge story — written with “cat eye sharp enough to kill a man.”