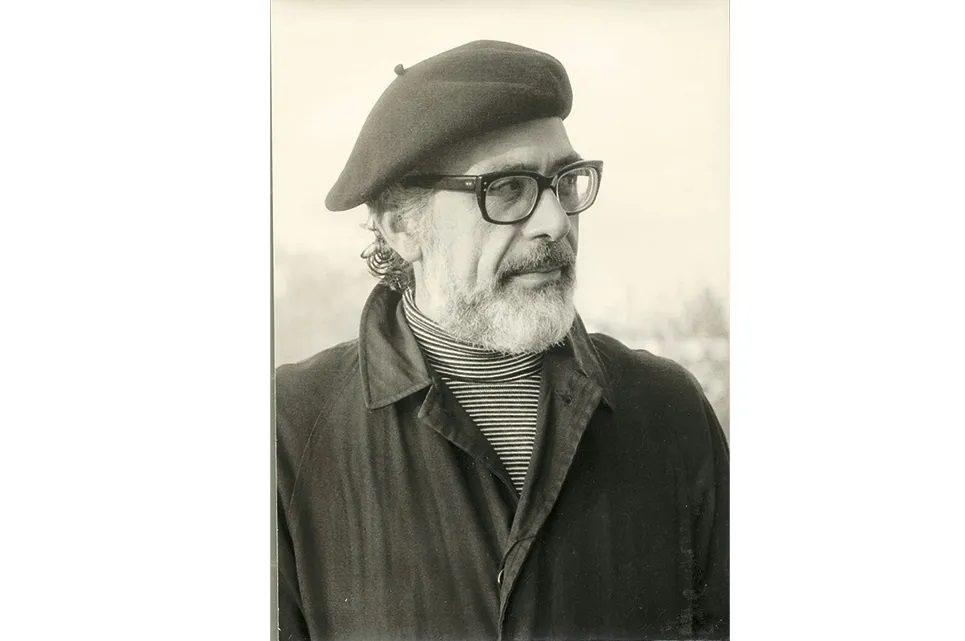

The NYRB logo is now something my eye leaps to when browsing, and the publisher’s eclectic range has proved consistently rewarding. The Argentine writer Antonio di Benedetto was praised by Borges, Bolaño, Cortázar and Coetzee. He was born in 1922, on November 2, the Day of the Dead — which he made much of — and was imprisoned and tortured in 1976-77, during Argentina’s Dirty War. His eerie fables of paranoia, impending threat and incomprehension pre-empted his experience of them. Esther Allen deserves great credit for introducing the author to an Anglophone readership. Having read her translation of Benedetto’s Zama, followed by The Silentiary, I found the wait for The Suicides excruciating. But it was worth it. The final part of this “trilogy of expectation” is, as it should be, a glorious anticlimax.

Zama, set at the end of the eighteenth century, is about an overlooked minor official stationed in remote Paraguay — neither native nor properly Spanish, frustrated and solipsistic. The narrator of The Silentiary (set in the 1950s) is overwhelmed by noisiness, unable to choose which of his acquaintances will be the victim of his unwritten murder mystery. In The Suicides a reporter in the late 1960s is commissioned to write a piece on suicides, particularly those whose eyes were open in post-mortem photographs. He is approaching the same age as his father was when he committed suicide — “on a Friday afternoon,” a detail both precise and oblique. He chafes at having to work with a photographer, Marcela, whom he describes as ascetic but for whom he has clearly stifling feelings.

The novels were not consciously written as a trilogy, but they have broadly overlapping concerns. The narrators see their lives as being in some kind of hiatus — on a threshold of real living — and all of them appear powerless to effect any change, or reconcile themselves to it.

The narrator of The Suicides collates various thoughts on suicide, from Durkheim, St. Augustine, the Tosafists and the Karaites — not to understand it so much as to distract himself. There is an encounter with a dog that keeps hurling itself against a plate-glass window, trying to jump out. Is the dog actually wanting to end its life (Aristotle thought a horse forced into incest had opted to be like Oedipus) or just stupid?

The novel is written in a laconic, lapidary style, very different to the standard image of recent Latin American literature — which is condemned in The Silentiary as “the odious odyssey of words,” and which the author slyly refers to as realismo magico, not lo real maravilloso. Benedetto may be understated, but he should not be underrated. Like so many in the NYRB imprint, the book is thrillingly singular. It perfectly dramatizes Nietzsche’s aphorism that the thought of suicide is a great consolation: by means of it one successfully gets through many a bad night.