Having been fired from World Championship Wrestling, Steve Austin entered the World Wrestling Federation with the godawful gimmick of ‘the Ringmaster’. He looked no more memorable than a Big Mac.

Austin knew that something had to change. He wanted to adopt an edgier, more cold-blooded character. The WWF’s creative team, displaying the genius that had inspired ‘Mantaur’, a wrestler who dressed up as a Minotaur, and ‘the Gobbledy Gooker’, proposed such names as ‘Otto Von Ruthless’ and ‘Chilly McFreeze’.

According to wrestling legend, Austin was at home when his wife told him to drink his tea before it turned ‘stone cold’. Stone Cold Steve Austin was born.

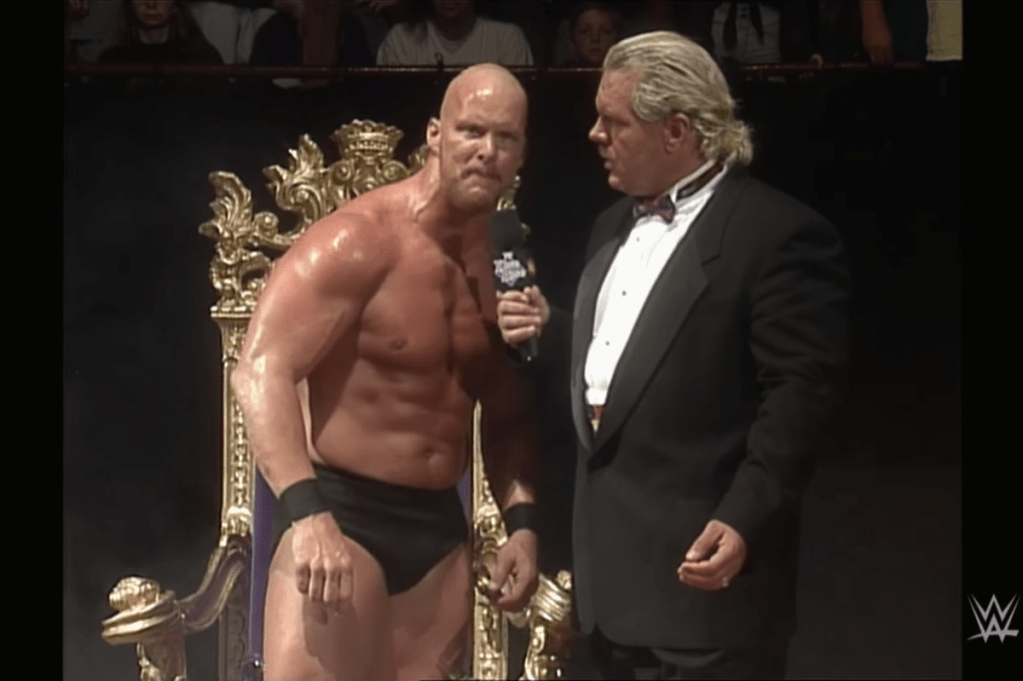

He quickly flourished. In June 1996, 25 years ago, Austin won the WWF’s ‘King of the Ring’ tournament and delivered his most famous promo. Mocking Jake ‘The Snake’ Roberts’ unconvincing, short-lived born-again Christian gimmick, Austin snarled: ‘You sit there and you thump your Bible, and you say your prayers, and it didn’t get you anywhere. Talk about your psalms, talk about John 3:16…Austin 3:16 says I just whipped your ass!’

‘Austin 3:16’ shirts became the best selling in wrestling history. For WWF fans, it was a breath of fresh air. For years, the product had been corny, childish and contrived, but here was raw, unfiltered and realistic contrived emotion. It helped to usher in the riskier, raunchier ‘Attitude Era’ of wrestling. But it also epitomized a broader cultural moment: the rise of the modern antihero.

It was through his feud against Vince McMahon, the owner of the WWF, that Austin reached true superstardom. McMahon, portraying himself a little too convincingly as a domineering, patronizing, dictatorial boss, continually tried to undermine Austin, who, in turn, would outsmart and kick seven shades of stool out of the hapless soon-to-be billionaire.

Austin was an unlikely hero: foul-mouthed, sadistic and mean. People loved him not in spite but because of those qualities. True, he was invading a hospital room to beat a patient round the cranium with a bedpan, but it was his scheming, overbearing employer. Managerialism, bureaucracy and political correctness were in the ascendance. People, especially men, loved to see an avatar of the common man standing up for himself — powerful and carefree. They might have destroyed a printer in Office Space. Austin destroyed the boss himself. Of course, in real life, McMahon was reaping hundreds of millions of dollars from such beatings.

Soon, even more questionable characters were attracting public esteem. Tony Soprano was on HBO. Walter White arrived as well, trading in his textbooks for a life of drug dealing. Even Dr House; in the real world, his antisocial and uncaring attitude would have had him fired 10 times before breakfast.

Adam Kotsko argues in Why We Love Sociopaths: ‘The sociopaths we watch on TV allow us to indulge in a kind of thought experiment, based on the question: “What if I really and truly did not give a fuck about anyone?” And the answer they provide? “Then I would be powerful and free.”’

I disagree somewhat with Kotsko when he suggests that people identify such do-not-give-a-fuckery with elite success. Be it Austin or House, admirers of these antiheroes see society as being oppressively bureaucratic and sterile, demanding rule bound compromise and conformism. These icons might be bad people but at least they are real — and their triumph is not so much topping the social hierarchy as transcending it.

Still, I think Kotsko was right about the identification of the antihero with freedom. The insightful anonymous blogger The Last Psychiatrist observed that such characters are very much not free. Tony Soprano, for example, has such a stressful and exhausting life that he has frequent panic attacks. But what matters is that he has the final say. We know a business owner’s life can be nightmare of taxes, expenses and elaborately hazardous retirement plans, but we still think of them as being somehow freer than an office worker peacefully doing what he is told.

The age of the antihero died with Walter White. Tony Soprano was a monster, but there were lines he did not cross. He never hit his wife and he never hit a child. Walter White, shifting from protagonist to antagonist, even poisoned a kid. The nihilism at the center of the sociopath had grown too morbid and oppressive to be as entertaining.

Antiheroes still exist, of course, as they always have. (As far as I can tell, Game of Thrones was exclusively populated by them.) But people were growing more attracted to superheroes — characters who might have had complexities and ambiguities but who ultimately did the right thing, on a grand scale. In higher culture, ‘sanctimony literature’, as Becca Rothfeld calls it in Liberties, was ‘full of self-promotion and the airing of performatively righteous opinions’.

Even in wrestling, uncomplicatedly heroic stars like John Cena, Daniel Bryan and Roman Reigns were on top, with diminishing returns. The cultural pendulum was swinging back, but also the politicization of culture in an age of Trump, Brexit and social media was demanding moral certitude and rectitude. A character’s sins had become their creator’s. Art was becoming more straightforwardly instructive.

Perhaps there is a balance to be struck between morbid cynicism and oppressive piety. One where characters attract us, repulse us and leave us unsure how to respond, much as they do in real life. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to go and watch Steve Austin drown Vince McMahon in beer.