One Saturday in 1975 a young man was walking through Macclesfield town center, without very much to do. He popped into Boots the Chemist and began flicking through their selection of records. After 10 minutes of random searching he found Patti Smith’s newly released LP Horses, and quickly returned home with it to Salford. As he recollects in his Autobiography, for Steven Patrick Morrissey finding Horses – in a pharmacy in Macclesfield of all places – was a defining experience:

‘Cross-legged by a dying fire later that night, and with only a side-light for company, I allowed Horses to enter my body like a spear… So surly and stark and betrayed, Patti Smith was the cynical voice radiating love… The past snaps. I have never heard or seen anything like Patti Smith previously, and I have never heard truth established so sincerely.’

This scene – a young person bored, with attention and time to spare, looking for music beyond the obvious and finding that music quite unexpectedly, then devouring it alone and in an almost embarrassingly profound way disappearing into that music and into the vision of the artist who created it – this scene no longer really exists.

For the contemporary equivalent of young Morrissey there would be no need to even leave his room to find new music, no need to take a bus to Macclesfield, no need to really do anything at all. He would simply download a streaming service like Spotify or Apple Music. Opening the homepage our user would be confronted by the nightmare of limitless choice (Spotify is the holding pen for over 35 million songs). He can choose from playlists curated by genre, by ‘mood’ and by newness. There are podcasts to stream, and videos too. On Monday Spotify will send him ‘Discover Weekly’ a bespoke playlist created by algorithms, based on our user’s listening habits. This space appears to offer unlimited freedom of choice but, as Liz Pelly explains, it is:

‘…tightly controlled by Spotify’s staff and dictated by the interests of major labels, brands, and other cash-rich businesses who have gamed the system.’

Spotify’s exponential growth and powerful machine-learning algorithms have changed the way music is consumed. Playlists, rather than albums are king; music is tailored to mood: chill, romance, focus; or to activity: party, workout, sleep. Pelly argues that this change has made music less diverse, less interesting and more like elevator muzak. Listening to music is not an aesthetic experience in itself (think Morrissey listening to Horses back in 1975) but something pre-programmed, inoffensive, ambient; an accompaniment to other activities. Streaming services have made entertainment feel like another form of work, another task, like answering emails, to be completed on a laptop or a smartphone.

In fairness to Spotify, it is hard to argue that exchanging $9.99 a month for a return of 35 million songs is not a good deal for the consumer. You might even have expected a radically democratic free-for-all to have developed on Spotify, now that anybody with an internet connection and some small change can find whatever music they want. Instead the service’s algorithms have shaped a generation of listeners who are defined, above all, by attention deficit disorder (nearly half of its users skip every song before it is finished) and a fear of complexity and difficulty.

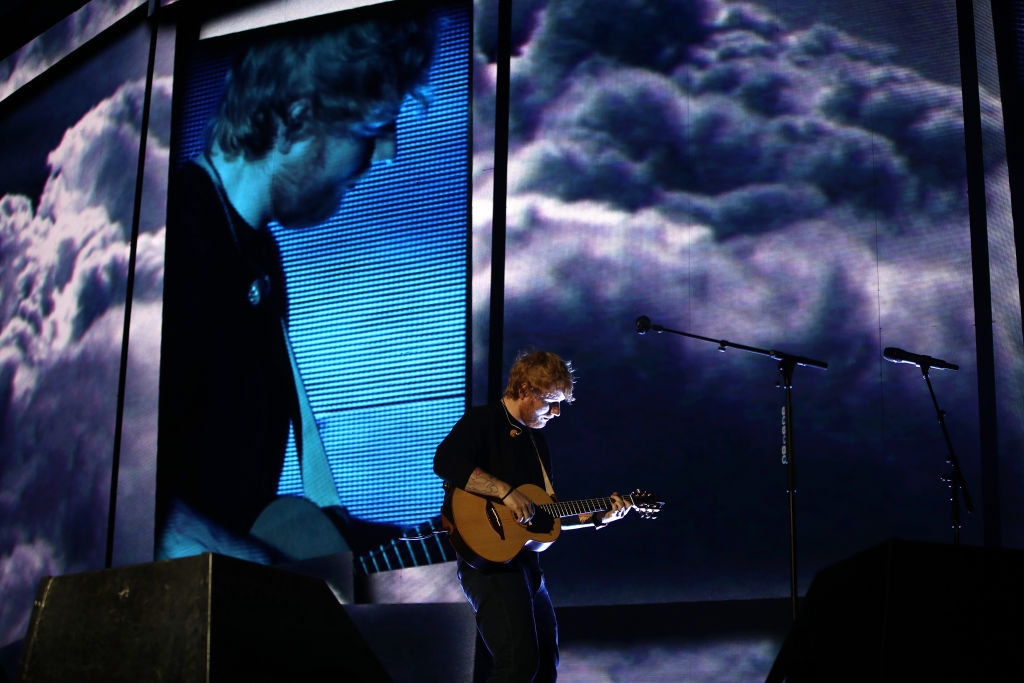

Ed Sheeran is the quintessential Spotify artist. Nice, safe, cheery, undemanding and globally ubiquitous. Oddly, for one of the world’s most popular musicians, there is nothing particularly sexy or cool or aspirational about him. (Would you want to be Ed Sheeran? Would you really want to look that weird?) Sheeran is simply, tyrannically present: on the radio, on the television, on social media; in clubs, pubs, bars; as background music in urinals and dentist’s waiting rooms and television advertisements. Shape of You, his hit 2017 single, has been streamed on Spotify more than two billion times.

Artists like Sheeran are now too big to fail. Fattened by the streaming services algorithms, he and others like him get bigger every year. In 2018 Sheeran, along with Taylor Swift, Beyoncé and Jay Z sold $1 billion in tour tickets. The decline in the sale of physical records has left touring as one of the last ways musicians can make decent money (last year artists received $0.0038 each time their songs were played on Spotify, and even then, the top 10 percent of artists dominate 99 percent of streams).

The touring industry is dominated by the top 1 percent of musicians. This bloated mafia squats atop the pyramid of concert earnings, squeezing the life out of the artists below them. Justin Bieber, Adele, U2, Coldplay, Bruce Springsteen, The Rolling Stones and others took home 60 percent of all concert revenues in 2017. This was the finding of the late Princeton University economist Alan Krueger who argues in his book Rockonomics that ‘the middle has dropped out of music, as more consumers gravitate to a smaller number of superstars.’

Fame, the novelist Jarett Kobek once deliciously observed, is the world’s last valid currency. Musical superstars have become so powerful that they can control and curate every aspect of their image. Beyoncé effectively interviewed herself the last time she was on Vogue’s cover and Taylor Swift refuses to be interviewed at all, though she does come down from Mount Olympus every now and then to pen hideous listicles for Elle magazine. The power and prominence of these monumental personalities appears as horribly stable as anything built by the slave empires of antiquity. Will they ever get off the stage?