This summer, a niche story from the art world caught fire: an Old Master painting, stolen by the Nazis from a Dutch-Jewish art dealer, surfaced in Mar del Plata, Argentina. Remarkably, journalists from a Dutch newspaper spotted it on the wall of a house in a promotional photo that was part of a “for sale” real-estate listing.

It turned out that one of the sellers of the house was the daughter of a Nazi official who worked for Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, a notorious art plunderer. When the stolen painting was recognized, the daughter allegedly removed it from the wall, replacing it with another artwork – a tapestry. Argentine authorities then arrested her and her husband and charged them with concealing a crime.

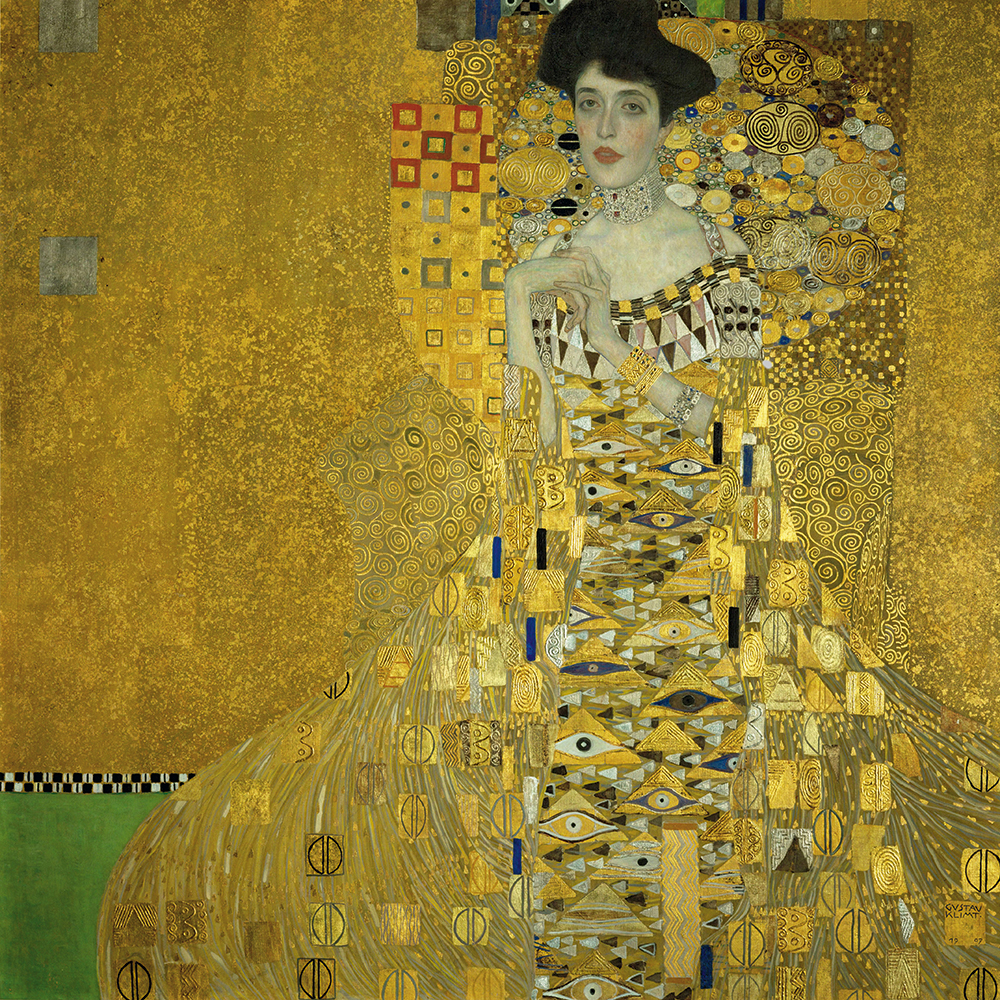

The story is not just another tale of Nazi-looted art, of which there are many. This one has deeper significance. It’s notable that the stolen art was found in a private home in South America. There have been many restitution claims for famous artworks in museums – “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” (known as the “Woman in Gold,” pictured above) by Gustav Klimt, found in the Austrian National Gallery or the Cassirer Pissarro, found in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, for example. But a far greater number of looted works remain in private hands around the world.

In 2000, the Presidential Commission on Holocaust Assets created by Bill Clinton estimated that the Nazis stole around 600,000 artworks, of which 100,000 are “missing” today. While these numbers are rough estimates (I helped compile them), they convey the truth that there is a lot of Nazi-looted art throughout the world that has been concealed from public view.

With generational change comes inheritance, and it’s now the children and grandchildren of former Nazis, war criminals or even Allied servicemen who possess the looted art. They offer a work for sale, only to discover it is stolen property. Many claims are resolved privately: a restitution specialist at the Christie’s auction house in London recalls that during her 15-year tenure, she helped resolve around 250 cases. Due to a lack of transparency or due diligence, individuals may have purchased or inherited a work without fully understanding its provenance. Accordingly, there are likely to be far more looted works in private hands that were never properly returned than the public understands.

In the case of this newly discovered Old Master – “Portrait of a Lady” by 17th-century artist Giuseppe Ghislandi – the possessor was Patricia Kadgien, the daughter of a powerful Nazi functionary who died in 1978. It was not just the top leaders such as Hitler or Göring who ended up with artworks looted from Jewish victims, but also their underlings. Göring looted “Portrait of a Lady” from Jacques Goudstikker in 1940 and took it to Germany, but he sent it back to Amsterdam, where his employee, Friedrich Kadgien, bought it from the “Aryanized” Goudstikker gallery in 1944. The Third Reich was a kleptocracy and its subleaders and functionaries found many ways to enrich themselves. The Ghislandi portrait was not the only one found with Kadgien’s daughter: 22 works by Henri Matisse were also discovered and are currently being researched.

I delved into the topic of looted art in the hands of Nazi functionaries in the recent documentary film, Plunderer: The Life and Times of a Nazi Art Thief, featuring Göring’s agent in Paris, Bruno Lohse; his looted artworks ended up in a bank vault in Zurich, as well as in his home in Munich. It should not come as a surprise that another Nazi agent working for Göring, Friedrich Kadgien, should have the Ghislandi portrait. It is significant that Kadgien and the artwork turned up in South America. We know that many Nazis fled Europe at war’s end. Adolf Eichmann and Josef Mengele are the most notorious, but an estimated 10,000 Nazis made it across the Atlantic, either through the Vatican-supported “ratline” or in some other way.

Experts in the field of Nazi-looted art have always suspected that a great deal of the plunder made its way to South America. Art is so fungible and transportable, and the market is international. We have had a few cases of such art popping up in Latin America, but there is much to do in this area. It’s an open secret that the region is flush with this artwork. One of the recommendations of the Clinton Presidential Commission on Holocaust-Era Assets was to bolster research into looted art in South America. The case of the looted Ghislandi should re-galvanize this effort. The Argentine authorities were aggressive in charging Kadgien and her husband with the alleged concealment of Nazi-looted art. By arresting them and charging them with crimes that could result in six years in jail, the Argentine authorities are making a statement. “The crimes that were being covered up are especially serious,” federal prosecutor Carlos Martínez told journalists after a court hearing at the end of October in Mar del Plata. “They are linked to crimes of genocide, to theft in the context of genocide.”

While US and European law enforcement officials pride themselves on forensic skills, the Argentine police are the first since World War Two to employ criminal statutes to arrest possessors of Nazi-looted art and to use the criminal proceedings against possessors to ensure the return of the artwork.

In the US in recent years, we have seen the restitution of Nazi-looted art not only through civil litigation, but also through criminal law. According to American law, there’s no such thing as a good title for stolen property. New York City District Attorney Alvin Bragg, along with his colleague Matthew Bogdanos, commenced criminal proceedings including seizures against US museums to compel them to hand over Nazi-looted artworks (notably, more than a dozen pictures by Austrian modernist Egon Schiele that were stolen from Viennese cabaret star Fritz Grünbaum). The tactic employed by Bragg and Bogdanos – leveling criminal charges against institutions – has been effective, leading to some of the most important restitution successes in recent years. Since World War Two, there has been a longstanding hope to complete the restitution process – a desire for closure. This began in the early 1950s, when Americans wanted to conclude the restitution work and focus on the intensifying Cold War. Efforts picked up again in the late 1990s when diplomat Stuart Eizenstat led efforts for a final reckoning regarding looted cultural property from World War Two.

Restoring Nazi-looted art has had bipartisan support in the US. The Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act (HEAR Act) of 2016, which helped Holocaust victims and heirs with their legal efforts to recover Nazi-looted art, became a milestone in the history of restitution. The law expires at the end of next year, but it is currently up for renewal, with continued bipartisan support. Indeed, some supporters of the renewal want to strengthen the provisions to aid victims and heirs. Yet, the New York Times and other media report that the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Association of American Museum Directors have been lobbying against such a step.

As the Times reported: “The museum also had a lobbyist meet with lawmakers and request they continue to allow time-barred defenses and include an expiration date on the legislation.” In the past, powerful institutions and individuals have fought restitution by using technical legal defenses, which is what led to the enactment of the HEAR Act in the first place, and the tactics highlight the need for the law to be strengthened. The tenacity of survivors and heirs is important. Marei von Saher, the heir to Jacques Goudstikker, said of her efforts: “My search for the artworks owned by my father-in-law Jacques Goudstikker started at the end of the 1990s and I won’t give up… my family aims to bring back every single artwork robbed from Jacques’s collection and restore his legacy.” So far, the Goudstikker family has recovered about 350 of the 1,300 pictures.

Art is expressive and intimately shared, often passed down from generation to generation; it has more than monetary value. For the past 80 years, the US had taken the lead in restitution efforts – an honorable legacy, even if the work is incomplete. The looted Old Master painting in Argentina shows us that the restitution of Nazi-looted art remains an important part of “the unfinished business of World War Two.”

As Jonathan Schwartz argued in a recent article in the Forward: “These works are not merely paintings or sculptures; they are fragments of stolen lives. Returning them is not charity; it is the fulfillment of justice long denied, part of an unfinished historical reckoning, one that museums should want to complete.” This case in Argentina reminds us that private individuals in possession of stolen art also have an obligation to return art that does not belong to them. And if they don’t, the law will come for them.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply