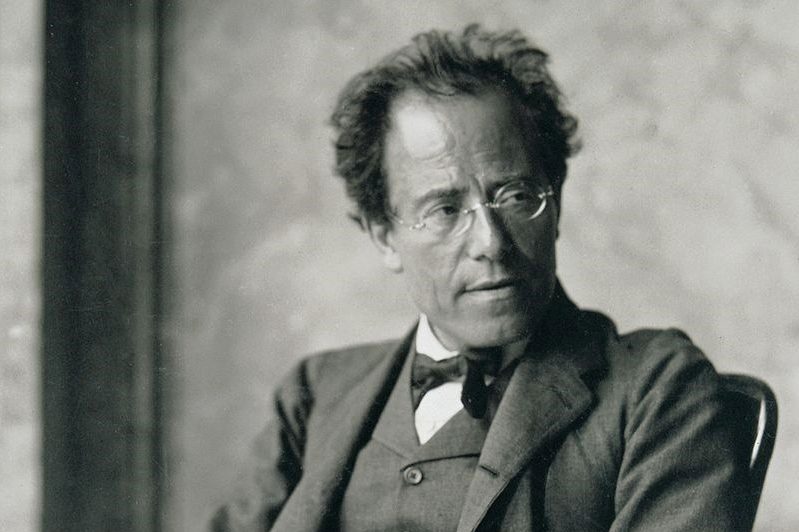

The photograph on the cover of Jessica Duchen’s magnificent new biography of Dame Myra Hess shows a statuesque lady sitting at the keyboard, hair swept back into the neatest of buns. Add a pair of half-moon spectacles and she could be Dr. Evadne Hinge, accompanist to Dame Hilda Bracket. This isn’t to imply that Dame Myra looked like a man in drag, but then neither did the “Dear Ladies” played by the musical parodists George Logan and Patrick Fyffe, some of whose fans thought the singing spinsters actually were women.

In their 1980s heyday, Hinge and Bracket were national treasures in Britain – and so, on a far grander scale, was Dame Myra, who lifted Londoners’ spirits with her National Gallery concerts during World War Two. If a bomb shattered windows and let in piercing winds, she wrapped herself in a fur coat and played on. When she died 60 years ago she was deeply mourned – but there was also a feeling that her “romantic” interpretations of Beethoven and Schumann had been superseded by those of Maurizio Pollini and other poker-faced modernists.

Was that fair? Stephen Kovacevich, Hess’s pupil during her final lonely years in London’s St. John’s Wood, says that “unfortunately the English started treating Myra like the Queen Mother, and she started playing accordingly. In America she did not play like the Queen Mother.” The American Steinways “released something in her… The English dried her up. She had a demoniac side… she was not the girl next door.”

Indeed not. Brought up in an Orthodox Jewish family in north London, young Myra acquired a phenomenal technique and a range of party tricks. She would play Chopin’s G-flat major Étude with the aid of an orange that she rolled over the black keys. She also liked to sing the sentimental ballad “The Rosary” (“each hour a pearl, each pearl a prayer”) a semitone flat with a straight face. It’s no surprise that she later became close friends with Joyce Grenfell.

According to Duchen, Myra’s sense of humor was so filthy that few published examples survive. But she has found one real marmalade-dropper: when Myra sent a gift of handkerchiefs to the violinist Jelly d’Arányi, she asked Jelly to think of her “when you wipe your arse on these hankies.” That would have come as a surprise to audiences moved to tears by Hess’s arrangement of Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring”; in all her recordings of it, the majestic chorale floating on the river of triplets conveys a serenity that few pianists have equaled.

Some people thought it strange that a hymn to Jesus should be the calling card of a Jewish musician. But Hess, while never renouncing her childhood faith and occasionally observing its feast days, saw no reason why she shouldn’t draw inspiration from Christianity. For many years her spiritual advisor was the Revd Ted Ferris, an Episcopal priest in Boston whose services she attended.

If she was bothered by genteel anti-Semitism, she didn’t let it show. But she did nurse one spectacular grudge – against the pianist Harriet Cohen, with whom she fell out over Harriet’s secret affair with Arnold Bax.

It’s hard to say whether Myra was jealous. All we know about her passions is that they were unrequited; whether she preferred men or women is a secret she took to her grave.

The sad truth is that Myra’s taste for comedy, combined with the halo of “national treasure” and the critics’ insistence on patronizing female musicians, ended up obscuring her greatness as a pianist. Listen to her searching and structurally ingenious performances of Beethoven’s piano sonatas opus 109 and 110; Solomon in all his glory recorded nothing finer. “She showed me that more deliberate tempos can be incredibly exciting,” says Kovacevich, which is certainly true of her titanic Brahms Second Piano Concerto.

French music was not her forte: one (Jewish) critic wrote that “her Poissons d’or sound as if they’d already been turned into gefilte fish.” Her Mozart concertos, on the other hand, could be gloriously exuberant; at first she wrote her own cadenzas but later said the memory of them made her ill – “masses and masses of arpeggios and the most terrible modulations.”

Duchen puts her finger on one of Hess’s special gifts – “a singerly technique that not all actual singers master.” It’s heard, to bewitching effect, in the recordings she made for Columbia in the late 1920s, when her command of the keyboard was at its peak. The familiar Gigue from Bach’s G-major French Suite dazzles with its delicacy, and it’s a matter of historical record that Myra set toes a-tapping.

When she played it at a party in 1937, Sir Walford Davies, venerable Master of the King’s Music, whisked Joyce Grenfell off her feet and began to dance. “Moments later all the guests had joined in,” writes Duchen.

Only Myra Hess could have pulled that off, demonstrating that you can be a magisterial interpreter of the great masters and still give Hinge and Bracket a run for their money.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply