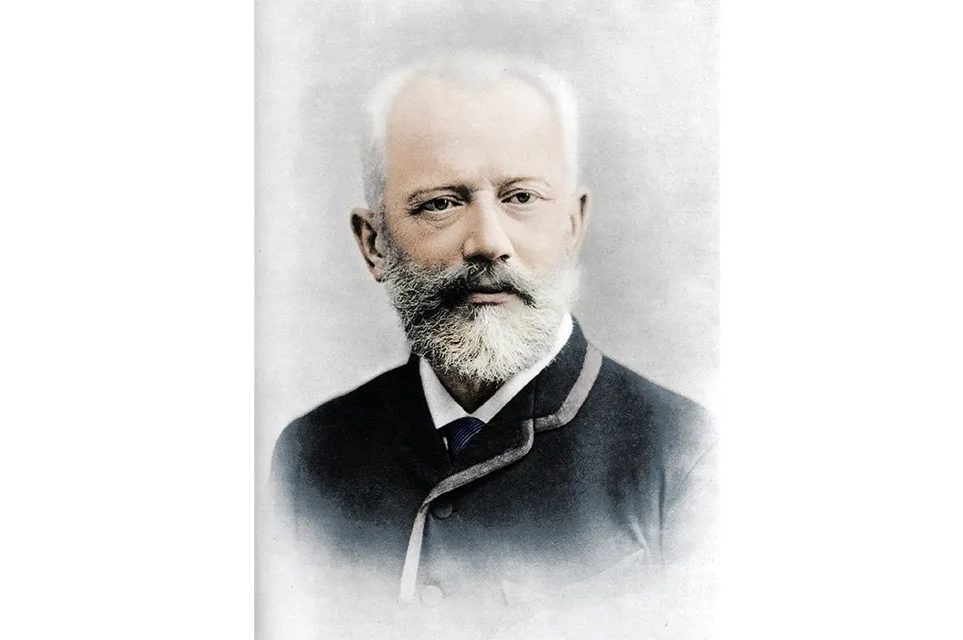

Some years ago, following a Christmas performance of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, I sat in one of the dives near the theater with a member of the corps de ballet, the gay son of close friends. The audience had been populated largely by children and teenagers, most of whom were either smitten by the intrepid, empathetic Clara or wanted to be her. Yet the mood perceptibly shifted when, at the end of Act I, the life-sized nutcracker doll transformed into a most handsome prince, all grace and gluts. “Do you think in that moment,” I asked my dancer friend, “that a smattering of adolescent boys, out on a family treat, notice their affections shifting from Clara to the Prince and receive there and then the gentlest yet unmistakable insight into their future selves?” “Oh absolutely,” he answered.

One could reasonably expect similar such tales of awakened, sublimated or explicit sexuality in a book about a famously gay and tortured composer (more on this in a moment), whose opening pages promise tales of rough trade and language, and whose distinguished author has talked of censorial predecessors excluding from their biographies anything that strayed from “the conventional and misleading suffering melancholic narrative.” Yet classical ballet, like much else here, is a strangely chaste affair. (The author’s contextualization and analysis of Tchaikovsky’s sensuous “Overture-Fantasia,” his retelling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, is a welcome exception.) And neither the bit-player rough trade nor the promised bounty from long suppressed archival sources shifts the narrative dial to any great extent.

Not that warhorses aren’t trotted out, prodded and then led back to their stall, a spring in their step. Simon Morrison is admirable in his treatment of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony — a piece historically lumbered with saddlebags of pathos and speculation owing to a program note Tchaikovsky sketched, yet never published, outlining the work’s arc of fate, doubt, lament and providence — traveling with ease through a century of psycho-sexual analysis.

Tchaikovsky appears as a sort of Till Eulenspiegel character, who laughs and pranks his way through life

The English critic John Warrack is one of the biographers Morrison identifies as determined to tragedize Tchaikovsky posthumously. Warrack asserted in 1974 that in this note, “it seems certain that Tchaikovsky is referring to his central emotional problem, his homosexuality.” Morrison is having none of this, blaming the correspondence between Tchaikovsky and his patron and pen-friend Nadezhda von Meck for perpetuating such misery memoirs, the dots between Tchaikovsky’s guilt over his sexuality and the pathos of particular works joined by crayon, so it seems. In their place, Morrison points to the altogether jauntier correspondence the composer enjoyed with his siblings — letters full of flatulence, diarrhea and various debilitating gastrointestinal conditions, no intimacies spared. Yet Russians then Soviets were spared such details — much as they were any lurid speculation concerning Tchaikovsky’s sexuality — lest they besmirch the character of this towering exemplar of empire and then state.

Similarly, the Fourth Symphony, about which Tchaikovsky wrote to von Meck (specifically the first movement’s barcarolle):

Everything gloomy and joyless is forgotten! Here it is, here it is — happiness! But no! They were daydreams… And thus all life is an unbroken alternation of harsh reality with fleeting dreams and visions of happiness

Elsewhere Morrison has complained about this letter, this morbid description and its grip on generations of biographers. “The worst thing Tchaikovsky ever did was write that letter to von Meck. In his letters to her, he does come across as always disappointed in himself,” leaving a gay-shaped shadow for historians to fill.

So, Morrison is right and bold to build his counter-narrative, creating as he does a sort of Till Eulenspiegel character who laughs and pranks his way through life until cholera catches up with him in St. Petersburg as the century closes in. All the while he composes works of great depth, pathos and craft — towering monuments to Russian late Romanticism. This would be more than enough for me in a relatively slender book.

Yet Morrison is determined to unfold this narrative against the backdrop of imperial Russia — his title intended to reference both the empire Tchaikovsky created around himself to produce these monuments and that of the nationalist Czar Alexander III in which the astounding work took place. And this is where Morrison’s stall looks a little understocked. Tchaikovsky was happy for Alexander’s coin — not least because of his poor relationship with the Czar’s father, Alexander II — and for the recognition it engendered. Yet he was in many senses a reluctant nationalist, by temperament and training, and found onerous some of the court’s expectations of him. This tension between Tchaikovsky’s ambitions and Alexander’s cultural tastes and autocratic tendencies, however, here remains mostly offstage, a little blurry as a consequence.

Morrison writes well, though I could do without the down-with-the-kids mannerisms that litter the pages. “Rubinstein drank. A lot.” Or this, about Rubinstein’s older brother Anton, who “played beautifully until he stopped practicing; he started to leave out the hard parts.” Morrison’s sorties into Tchaikovsky’s posthumous centuries are similarly clunky, partly because of the odd fights he picks along the way. The Texan pianist Van Cliburn, who won the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958 with a performance of the composer’s “Piano Concerto No. 1.” is charged with “inaugurating a musical arms race that bulked up the concerto and excised all subtlety from it.” Yet all Cliburn did was play the posthumous edition of the work — with the strange cuts, altered passages and strident block piano chords in the opening pages — through which it became one of the most recognized classical pieces of all time. “Van Cliburn played the concerto throughout his career like a record on repeat, wearing out the grooves,” Morrison adds. Well, he did a lot of other things besides.

Morrison is similarly snippy about the brilliant pianist Kirill Gerstein, who recorded the recent Urtext edition of this concerto, prepared by the Tchaikovsky scholar Polina Vaydman and her daughter Ada Aynbinder, rolling the opening chords and restoring the cuts. (“He claims that he researched the history of the concerto — by which he means that he relied on the multivolume 2015 critical edition.”) Vaydman’s edition is based on the 1879 version Tchaikovsky conducted nine days before his death, alongside the premiere of his “Pathétique Symphony.” If you ask Gerstein (I did), he’ll say “there is not a single shred of evidence in Tchaikovsky’s hand that Tchaikovsky changed these chords,” nor is there proof of a third version or associated materials appearing in Tchaikovsky’s lifetime. “And no, I merely play the Urtext edition that they prepared. Vaydman was and is always credited…”

If you ask Garrick Ohlsson about Cold War posturing in the concerto at the time his fellow countryman bagged the Tchaikovsky gold medal, twelve years before he himself would attain similar honors in the Chopin Competition (I did), he’ll say that his ten-year-old self “already owned Rubinstein (not un-grand) and Horowitz (definitely aggressive?) recordings and wasn’t aware of stylistic trends.” Morrison’s unforced errors thus give me pause about some of the other spats and analytical byways he embarks upon; sometimes a better explanation is at hand. As Ohlsson says: “Seems that the Cold War and modern era of pianism coincided. The Soviet pianists of the time, particularly young ones, like their American colleagues, excelled in mechanical brilliance and a hard edge.” It’s how everyone played the thing; recordings had been eradicating national quirks and traditions since the 1930s, as had key pianists before then.

My undergraduate years seem a long time ago now, for indeed they were. They unfolded late in the decade in which the English musicologist David Brown proposed that Tchaikovsky died not from cholera but from arsenic poisoning, decreed either by the czar or a hastily convened “court of honor” made up of Tchaikovsky’s peers, incensed by the composer’s alleged affair with the nephew of Duke Stenbock-Thurmor. This is meant as no disparagement of a fine scholar, but the 1980s was the perfect time for such a theory to emerge, mutate and spread widely; Aids, HIV, homophobia and sexual panic were the decade’s catch-calls. I vividly remember the fevered currency of Brown’s proposition (“that he committed suicide cannot be doubted”), which seems scarcely believable today. Certainly, and admirably, Morrison doesn’t believe it, demonstrating the judgment we have come to expect from this eminent scholar. And though this book is a welcome corrective to the Warracks and the Browns and the generation of gay musicologists that followed them, niggling caveats remain.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.