When it comes to music in the classical era, central Europe — or, to put it is where most of the action has taken place. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms are, in a sense, the Big Five, commanding the limelight, with the likes of Mendelssohn and Mahler bringing up the rear. But if geography has somehow played a key role in the development of modern classical music, then another region has been gradually nudging its way into view.

Names from northern Europe such as Kalevi Aho, Leif Segerstam, Per Nørgård and Vagn Holmboe must figure prominently in any tally of leading composers who have expanded the boundaries of musical expression.Take Holmboe’s brilliantly imaginative Concerto No. 11 for trumpet and orchestra. As played by the Swedish trumpeter Håkan Hardenberger on a nifty 1996 BIS recording, it showcases both the heraldic and brooding capabilities of the trumpet, flashing brilliantly at times and wistfully at others.

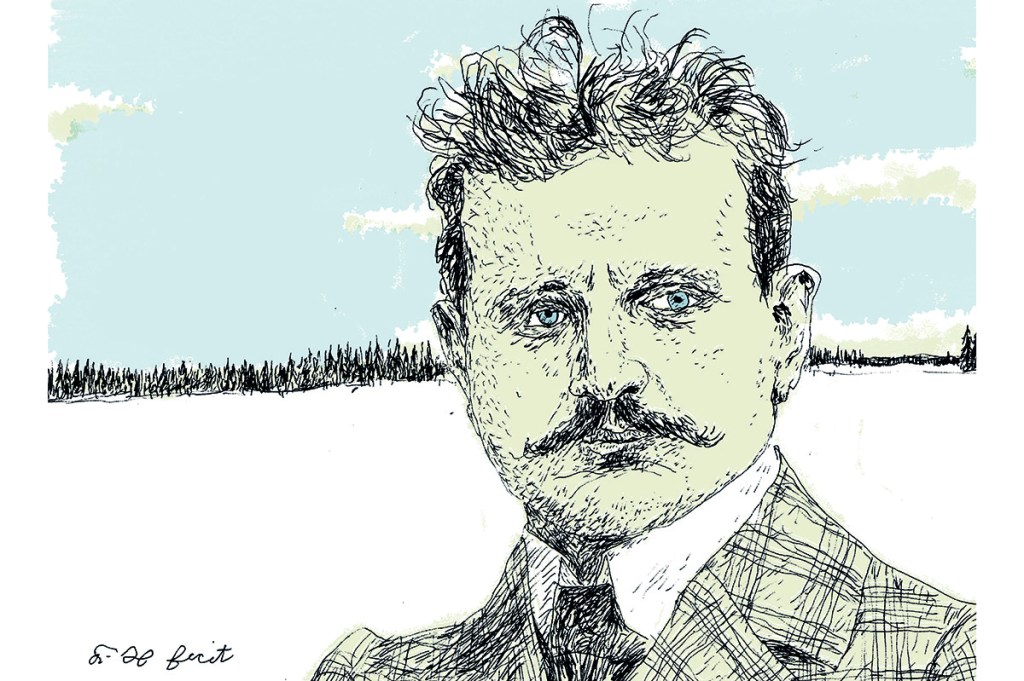

The head honcho of these composers is, of course, Jean Sibelius. There is something not just musically but also physically imposing about Sibelius, whose bulging cranium resembles a giant iceberg. Stare at a photograph portrait long enough and you may start to feel that he is staring at you. Indeed, just looking at his stern visage brings to mind the immortal exchange between Bertie Wooster and Jeeves on the subject of mental faculties: “‘It’s brain,’ I said, ‘pure brain! What do you do to get like that, Jeeves? I believe you must eat a lot of fish, or something. Do you eat a lot of fish, Jeeves?’ ‘No, sir.’ ‘Oh, well, then, it’s just a gift, I take it; and if you aren’t born that way there’s no use worrying.’”

Pure brain — Sibelius had it too, in spades. So when I learned from Bob Attiyeh, the intrepid producer of Los Angeles-based Yarlung Records, that he had overseen a new recording of a seldom-performed work from Jean Sibelius, I leapt at the chance to hear it. Soon on my doorstep was Sibelius’s Korppoo Trio in D major, recorded by the Sibelius Piano Trio in 2016 (with the special permission of the Sibelius Foundation) to mark Finland’s hundredth anniversary of independence from Russia. Indeed, with the Kremlin reverting to type and menacing its neighbors once more, this LP’s arrival could hardly have been more timely.

It almost goes without saying that Sibelius’s work is intimately bound up with his homeland’s history. Finland was colonized by Sweden in the twelfth century. It was annexed from Sweden by Russia in 1809, which transformed it into an autonomous Grand Duchy within Russia’s sprawling empire. The ill-fated Nicholas II sought to implement a policy of “Russification” in 1899. But after the collapse of the Romanov dynasty during World War One and the rise of Bolshevism, Finland officially declared independence in December 1917.

Finland’s trials were not over. In November 1939, Stalin invaded. The unexpectedly stiff resistance he encountered prompted the Kremlin to sign the Moscow Peace Treaty with Finland in March 1940. For those American communists who insisted that good old Uncle Joe was a peace-loving leader, the Soviet invasion came as something of a blow. But even the Trotskyists, who had claimed that the USSR was a “degenerated workers’ state,” tried to suck it up, arguing that the attack might lead to the liberation of the Finnish proletariat.

Then came the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Hitler and Stalin. That put the kibosh on any lingering illusions about Stalin’s Soviet Union. Today, Russia’s malodorous tradition of trying to subjugate its neighbors continues under Vladimir Putin, who apparently flew a military cargo plane over Finland in January just to show that he can.

Whether Sibelius himself was really a nationalist is up for debate, but he undoubtedly helped his country create a national identity. Before independence, Finns were outraged upon hearing that the Soviet authorities banned performances of his overture Finlandia. I suspect that had they been able to hear the thunderously rousing version recorded by Herbert von Karajan with the Berlin Philharmonic on the EMI label in 1977, they probably would have gone into paroxysms. Sibelius himself had a penchant for dramatic sonic climaxes. He confessed after losing some forty pounds at the 1918 siege of Helsingfors that “the crescendo, as the thunder of the guns came nearer, a crescendo that lasted for close on thirty hours and ended in a fortissimo I could never have dreamed of, was really a great sensation.”

Sibelius, who was born in the Grand Duchy on December 8, 1865, studied to become a lawyer, but he began composing at an early age. One of his efforts was the Korppoo Trio, which he composed in 1887 while vacationing during the summer on the southwest Finnish archipelago with his brother Christian, a cellist, and sister Linda, a pianist. Jean played the violin part.

The Sibelius Piano Trio’s live concert, featuring Petteri Iivonen on violin, Juho Pohjonen on piano and Samuli Peltonen on cello, is a treat to hear. For one thing, Yarlung Records, which always goes to great lengths to ensure high recording quality, down to the microphone amplification and tape machines it employs, has produced another sonically stellar LP. The individual instruments are almost perfectly balanced and the timbral fidelity is impeccable.

The pleasure that Sibelius must have had in playing with his siblings on a work that he himself had composed comes through in the new recording. The opening movement (Allegro moderato) is alternately majestic and playful, with especially fleet and jaunty piano runs from Pohjonen towards the end of it. Pohjonen’s playing throughout is characterized by a refined and elegant sensibility.

The Romantic character of the trio comes to the fore in the andante second movement (Fantasia), where Sibelius ensures that the cello has a melancholy singing line in tandem with the violin. Later in the movement, the violin’s delicate solo birdcalls in the treble could hardly be more evocative. Then comes the rollicking Rondo finale which closes with a bang. It’s all a long way from the early days of the trio form, when Haydn assigned the cello a distinctly subordinate role. The first major composer to really bring the cello into its own in the trio was Beethoven; compositions in that arena, including his Ghost Trio and Archduke Trio, must surely rank among his greatest.

No one will confuse this youthful piece (whose score has never been published) with Sibelius’s later works, but he had clearly had game from the outset. Listening to the Korppoo Trio prompted me to return to records of some of those ensuing compositions, including a venerable Decca LP of Kirsten Flagstad singing a variety of his songs with the London Symphony in 1958. Sibelius wrote almost one hundred songs, but most were set in Swedish. The song “Was it a Dream?” has a highly operatic, almost Wagnerian character, forcefully and plangently brought to the fore by Flagstad, often accompanied by the shimmering strings that are a special Sibelian touch.

Next, I turned to the Angel pressing of Ida Haendel playing Sibelius’s Violin Concerto with the Bournemouth Sym- phony Orchestra in 1986. The violin concerto was written in 1903 and was apparently something of a flop, the conductor Victor Nováček being overwhelmed by the music. Sibelius then revised it, and Richard Strauss conducted it in 1905 with the Berlin Philharmonic.

To listen to the Polish-born Haendel, who died in July 2020, play the concerto is riveting. Now a standard part of the orchestral repertoire, it poses numerous challenges, but Haendel unites technical virtuosity with deep musicality to master it. She brings firepower to the piece, soaring above the orchestra. Throughout, Sibelius’s own immense imaginative powers are fully apparent. He was a traditionalist who established a new tradition in northern Europe that continues to enrich classical music. Gifted indeed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.