‘Was Shakespeare a Woman?’ Elizabeth Winkler asks in the new issue of The Atlantic. Of course he was.

If you believe that Shakespeare was not Shakespeare, but Francis Bacon, or Walter Raleigh, or the Earl of Oxford, or Christopher Marlowe, or even Emilia Bassano Lanier, then you have succumbed to a conspiracy theory. A pity that, given the public’s increasing willingness to believe anything, and some people’s increasing willingness to publish anything, that this conspiracy theory should be promulgated in The Atlantic, a magazine with a long, albeit lately abandoned, tradition of intelligent writing on literature.

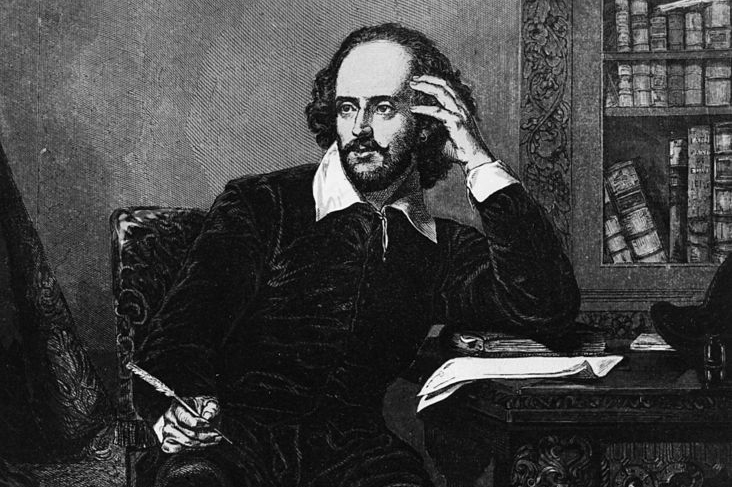

Since Shakespeare’s ascent to divinity in the 19th century, every generation has invented the Shakespeare it needs, even when the Shakespeare it needs is an anti-Shakespeare. Hence this fantasy of an anti-Shakespeare that inverts the pale, male ‘Stratfordian’ truth to invent a female, Jew-ish, black-ish proto-feminist daughter of immigrants.

There are always clicks to be made from trendiness and contrariness. But I was surprised to find that Elizabeth Winkler was making them. On April 22, she reviewed Shakespeare scholar Jonathan Bate’s How the Classics Made Shakespeare for The Wall St. Journal. She cited Bate’s use of the pronoun ‘he’ for Shakespeare without disagreement. She even described Shakespeare as a ‘country boy from Stratford-upon-Avon’, which is a traditional as it gets.

Now, less than a month later, Winkler doubts all of this — even though she admits that there is ‘no obvious resemblance’ between the style of the poems published in 1611 by her substitute Shakespeare, Emilia Bassano Lanier, and the style of the play that Shakespeare apparently didn’t write in that year, A Winter’s Tale. Has Winkler had a Bardic epiphany? Or has she misrepresented her beliefs in one of these two articles?

The ‘case’ for anyone but Shakespeare is always a fantasy in pursuit of facts. Winkler’s article, like every case for Shakespeare not having been Shakespeare, repeatedly commits the elementary error of historical writing. Absence of evidence does not mean evidence of absence. It is strange that Shakespeare doesn’t refer to books in his will. But it doesn’t mean that he didn’t read. Hitler, after all, did not attend the Wannsee Conference. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t order the Holocaust.

‘Everything in here was rigorously fact-checked by The Atlantic,’ Winkler insists. In which case, The Atlantic has further reason to be embarrassed. Here are five inaccuracies from Winkler’s article:

‘The authorship controversy, almost as old as the works themselves’.

Not true. The authorship controversy is a modern artifact, and one of the first modern conspiracy theories. The idea that someone else was ‘Shakespeare’ first took coherent, conspiratorial form in The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded (1857) by Delia Bacon, no relation to Francis. She later went mad.

To root the authorship controversy in Shakespeare’s lifetime, Winkler conflates contemporary rumors with a modern cult. Early in his career, Shakespeare may well have lifted lines from other writers and taken the full credit for collaborations. These were typical practices in the pre-copyright Elizabethan theater. They remain typical practices in the arts, especially in music, film and television. Taking inspiration and credit from others has nothing to do with the ‘authorship controversy’, which fantasizes that Shakespeare wasn’t Shakespeare at all.

Irrelevant interpretation: Gabriel Harvey’s ‘excellent Gentlewoman’.

In a letter of 1593, the scholar and gossip Gabriel Harvey referred to an ‘excellent Gentlewoman’ who had already written the ‘immortal work’ of three sonnets and a comedy. Winkler nods to the most likely recipient of Harvey’s flattery: Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke and sister of poet, soldier and pioneering literary theorist Sir Philip Sidney, and also a candidate for ‘Shakespeare was female’ theorists. ‘Was Shakespeare’s name useful camouflage, allowing her to publish what she otherwise couldn’t?’ Winkler asks, but then finds a woman more suited to the vanities of our time: ‘But the candidate who intrigued me more was a woman as exotic and peripheral as Sidney was pedigreed and prominent.’

Never mind that Shakespeare, the son of a provincial glover who fell on hard times, started his career in London as a peripheral stranger. The problem here is that by 1593, Shakespeare had written much more than three sonnets and a comedy. The New Oxford Shakespeare (2016) identifies Shakespeare as sole author of five plays, co-author of another three, and also as the author of two long poems, ‘Venus and Adonis’ and ‘The Rape of Lucrece’. So whoever Harvey’s excellent Gentlewoman’ is, she has nothing to do with Shakespeare.

False claim: Emilia Bassano’s family were ‘likely Jewish’.

The five Bassano brothers arrived in England from Venice in 1531, to work at the court of Henry VIII. It is quite possible that the Bassano family were of Jewish origin. Winkler writes that ‘scholars suggest the family were conversos, converted or hidden Jews presenting as Christians’. But there are no grounds to believe that Bassano’s alleged Jewish background informed her life in any significant way.

The problem with this ‘likely Jewish’ claim is threefold.

(i) As ‘absence of evidence’, the Bassanos appear nowhere in the Inquisition’s highly accurate reports on the tiny, crypto-Jewish community in Tudor England. The Bassanos, if they were ‘hidden’ Jews, would have been the most prominent and enduring feature of a floating community.

(ii) As ‘evidence of absence’, Emilia’s mother Margaret Johnson was an English Christian. Emilia’s book of verse, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (1611), shows her to have been a fervent Christian.

(iii) As Benzion Netanyahu demonstrated in The Marranos of Spain (1966), the idea that conversos remained ‘hidden Jews’ has romantic appeal, but little historical foundation. The majority of converted Jews were not ‘hidden’: they were Christians.

False claim: Emilia’s ‘Bassano lineage’ also ‘helps account for the Jewish references that scholars of the plays have noted’.

If the rest of Winkler’s account of Emilia Bassano Lanier is vaguely accurate, then this is impossible. Winkler does not mention that she derives this theory from the ‘Bassano was Shakespeare’ conspiracist John Hudson, whom she describes in her article as unreliable: someone whose ‘zeal can sometimes get the better of him’.

Hudson’s alleged evidence for Bassano as Shakespeare’s Jew includes not just the humanizing of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, but also the claims that A Midsummer Night’s Dream ‘draws from a passage in the Talmud about marriage vows’ and that ‘spoken Hebrew is mixed into the nonsense language’ of All’s Well That Ends Well.

In the Dream, Helena compares herself to Hermia by the criteria of beauty, fairness and height. It is true that the same criteria appear in the Babylonian Talmud, in Tractate Nedarim’s discussion of annulling marriage vows. This is striking and intriguing, but it does not prove that Shakespeare ‘draws’ directly from the Talmud. After eight decades of living and intermarrying in England, the Bassano family were well on their way to being believing Christians like Emilia. Or are we to believe that they were born with a knowledge of the Talmud? It is much more probably that Shakespeare was as unaware of the provenance of Helena’s categories as the child who says ‘Abracadabra’ without knowing that she ‘draws from’ the Aramaic for ‘I create like the word’.

There is no reason to infer that ‘spoken Hebrew is mixed into the nonsense language’ of Act IV.i of All’s Well That Ends Well. John Hudson, throwing etymology to the winds, translates Shakespeare’s ‘Boscos vauvado’ into the Hebrew ‘B’oz k’oz ve’vado’: ‘In bravery, like boldness, in his surety.’ But the rest of the scene’s nonsense language is a mulch of Romance languages. The Norton Shakespeare describes this scene, which is set among the soldiers of a Florentine camp, as being ‘in ambush’. ‘Boscos’ almost certainly derives from the late Latin boscus, ‘a wooded location’. Later, in Act IV.iii, Shakespeare uses ‘Bosco’ in word the specifically Romance formulation, ‘Bosco chimurco’. So much for Winkler’s ‘spoken Hebrew’.

False claims: Ralph Waldo Emerson ‘concurs’ with ‘illustrious names’ like Whitman, Twain, Henry James, Sigmund Freud, Helen Keller, and Charlie Chaplin that ‘Shakespeare is not the man’ who wrote Shakespeare.

In Representative Men (1850), Emerson struggles to understand how ‘the best poet led an obscure and profane life, using his genius for the public amusement’, and how while most ‘admirable men have led lives in some sort of keeping with their thought’, the extant facts of Shakespeare’s life suggest a ‘wide contrast’ between work and life. Nowhere in his essay does Emerson deny that Shakespeare was a man called Shakespeare. He did, however, encourage the enquiries conducted by Delia Bacon before her decline from fantasy to total lunacy led to her incarceration.

Nor did Henry James ‘concur’ about the non-existence of Shakespeare. The writer of uncanny stories only admitted to being fascinated by the idea, and came to no conclusion: ‘I am “sort-of” haunted by the conviction that the divine William is the biggest and most successful fraud ever practiced on a patient world.’

*