The crypt of St. John’s Waterloo feels serene and secure, a world away from the bustling London above. “I will spend the day here, because I feel safe here,” Badiucao tells me. The dissident political cartoonist, who has been called “China’s Banksy,” is preparing to display his work on the crypt’s newly restored brick walls as part of an exhibition by exiled artists. “I don’t walk alone in any city. I don’t feel safe,” he says.

I meet him soon after he flies in from Warsaw, where the Chinese government tried to close down his solo show, “Tell China’s Story Well.” Chinese diplomats pressured the Polish government and the Ujazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art, which hosted him. “They said it would damage relations between Poland and China, that it would hurt the feelings of the Chinese people — as if I am not Chinese,” he says.

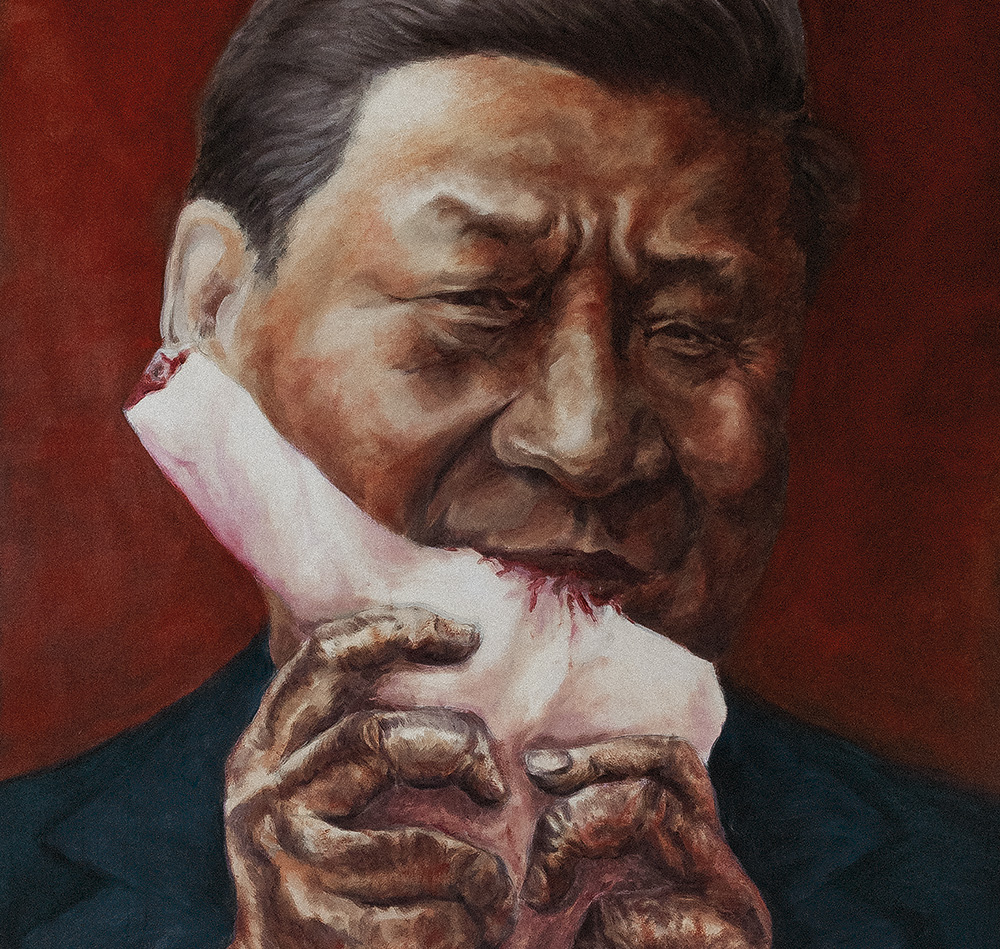

When Yao Dongye, a senior Chinese diplomat, turned up at the museum uninvited and demanded a meeting, he was told he needed an appointment and sent away. The gallery expressed its “concern and astonishment,” and when Yao returned it presented him with a signed copy of the poster of the show. The poster depicted Xi Jinping devouring a child, an homage to Goya’s “Saturn Devouring His Son.” “Pay attention to his face when he sees the poster,” says Badiucao, as he shows me a secretly filmed video of the encounter. Yao recoils from the poster as if it were something toxic. “Obviously he didn’t like it,” Badiucao chuckles. “It’s not an easy image, it’s very brutal. But it’s reflecting what is happening in China. The father is eating his child because he is afraid he will uprise and replace him.”

The Chinese government tried and failed to stop earlier shows in Italy and the Czech Republic, but Badiucao says there was far more menace in the threats in Poland. “It’s getting worse. Usually when they say it’s hurting the feelings of the Chinese people it’s just a slogan. It’s hollow. It’s propaganda. This time they gave it substance, suggesting it was hurting the 20,000 Chinese students studying in Warsaw. They were implying there might be consequences.”

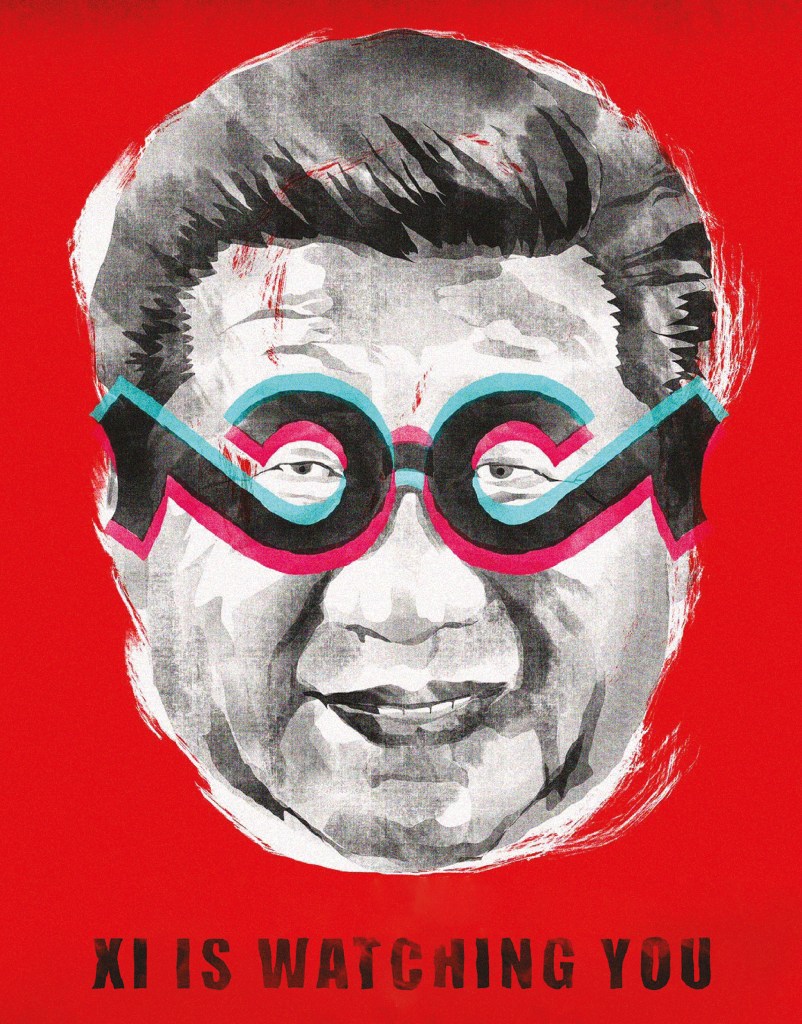

Xi with glasses fashioned from the TikTok logo (Badiucao, U-jazdowski)

He was in London for three days and wanted to visit an exhibition at the Design Museum by his fellow exiled dissident artist Ai Weiwei, but decided it was too risky. “I have also been followed physically by agents, possibly Chinese agents. There are death threats almost on a daily basis from social media. Even people who work with me are experiencing similar things.”

For the London show, Banned by Beijing, which is a group exhibition, Badiucao contributed several posters, including Xi devouring the child, and a matching one of Vladimir Putin. Another poster depicts Xi wearing a funky pair of glasses, fashioned from the logo of TikTok, the Chinese-owned app. The title is “Xi Is Watching You.” Has there been pressure from Chinese diplomats in London? “I am not aware of it, but I am pretty sure there will be eyes and ears poking around the event,” he says. However, the webpage of Index on Censorship, who organized the show, was knocked offline in a suspected hacking and Twitter was flooded with fake accounts claiming to be Badiucao in an effort to discredit him.

Badiucao — who still keeps his real name a secret — was born in Shanghai in 1986. He studied law before moving to Melbourne as a student in 2009. He worked as a kindergarten teacher before beginning to dabble in political art, adopting the pen name Badiucao to protect his identity. He says it was randomly chosen, with no meaning. In public, he often disguised himself as a woman with big sunglasses, or else wore a multicolored ski mask. His satire includes a cartoon of Xi posing like a trophy hunter holding a rifle next to a dead Winnie-the-Pooh, which he drew after the Communist Party banned the bear of very little brain from the internet because he was being compared to Xi. Another one of his works showed Xi’s face morphing into a skull, shortly after China’s leader abolished time limits on his rule.

In 2018 he was preparing for an exhibition in Hong Kong when the Chinese government discovered his identity, possibly as a result of digital surveillance. Chinese police visited and interrogated his family and friends in Shanghai. He canceled the show, fearing for the safety of his loved ones. He also feared he might be snatched from the streets of Hong Kong, which was then nominally autonomous. “You know I’d been anonymous for a very, very long time, and I knew that once they know my identity, it’s not just me, it’s my family, my friends, anybody who worked with me previously would be in trouble. So I had to be very, very cautious.” A year later, he revealed his face for the first time in a television documentary.

Pressure on family left behind is a well-honed CCP technique for intimidating dissidents abroad. A member of Shanghai’s Public Security Bureau once described it this way: “A fugitive is like a flying kite: even though he is abroad, the string is in China.” Badiucao took the painful decision to cut ties with his family. It was the only way of protecting them and his art. “I made a decision to not contact or connect with them any more. Because this is what the Chinese government does. They know they can manipulate you by putting pressure on people who you care about or are connected to you.”

Under Xi, the CCP has increased its efforts to silence dissent at home and abroad. Badiucao’s artwork strikes a particularly raw nerve. He is prolific on social media, and despite the CCP’s tight internet controls, he is confident his images do find their way into China. He is now China’s best-known political cartoonist. His big and bold graphic images use imagery from CCP propaganda and turn it against the party. “It is very explicit and direct, but also carries a simple message.” One popular recent image is a baby Putin suckling on Xi’s breast. When a Chinese spy balloon crossed the United States, he created an image of Winnie-the-Pooh dangling from a balloon and looking down with a pair of binoculars towards a wary-looking bald eagle. He’s particularly pleased with his Winnie-the-Pooh cartoons. “They are probably the most iconic works I have done.”

Badiucao now has Australian citizenship, though that has not protected him against harassment. Indeed, Australia has proven to be a very difficult place to exhibit his work, with galleries reluctant to work with him. For private galleries, it is a familiar story of commercial pressure. “China is a huge investor in the contemporary art market,” he notes, “and in order to maintain that market, they won’t present me.” Public institutions also fear accusations of Sinophobia — a concern which the CCP knows how to exploit. “The mixing of party, people and nation is their way of getting away from a lot of criticism,” he says. As a result, even though Badiucao’s work thrives online, he finds it hard to get a physical platform in his adopted country.

Badiucao has an easy smile, and in spite — or possibly because — of all the pressure he is able to see humor in the darkest of corners. He says his aim is simple: “To be a voice for people inside China who cannot speak for themselves, and also to introduce what’s happening in China to the broader world. That makes me a troublemaker and a target for them, and I do think that art has tremendous power in highlighting human rights abuses and pointing out the problem of the regime.”

He is inspired by German expressionist artist Käthe Kollwitz, known for her portrayal of the downtrodden, including peasants and working-class people affected by poverty and hunger during wartime. During the 1930s, her style was adopted by left-wing Chinese artists who believed “art should serve society.” Then the CCP “kept the style, but changed the subject,” Badiucao says. “They used the same style and propaganda language against anybody who wants to challenge them. I want to bring it back to Käthe Kollwitz, when it is truly speaking for the voiceless.”

He believes the apparent strength of Xi disguises a weakness inherent in all dictators. “They can be perceived as mighty, but at the end of the day, it is also very fragile, because it is impossible to control everything. It’s not sustainable, you just need a little crack, and obviously artists are crack-makers for any society because we pose questions, we challenge.” His next project is a graphic novel, tentatively titled You Must Take Part in the Revolution. He may be a target of Xi’s agents, but he still sees plenty of cracks to exploit.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.