In 1835 the first two Egyptian antiquities were registered in the British Museum: a pair of red granite lions from Nubia. Each bore the name of Tutankhamun — not that anyone had ever heard of him.

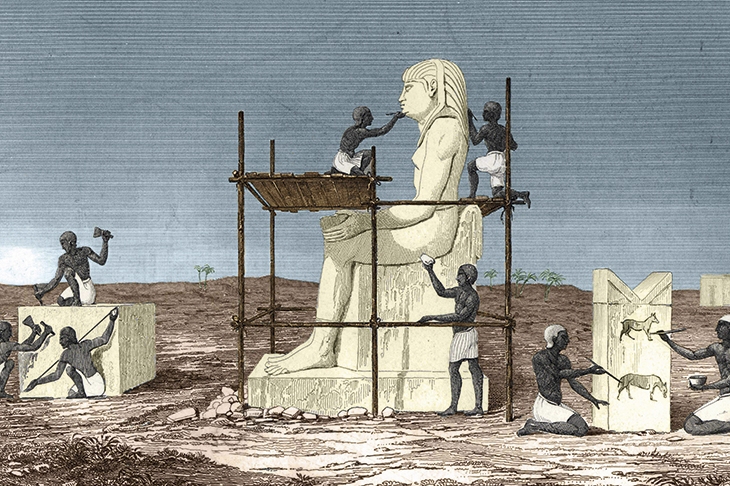

All serious understanding of the millennia-spanning Nilotic civilization had disappeared before the last hieroglyph was carved in 394 AD. In the mid-18th century the most advanced ‘scholarship’ on the subject consisted of ‘pinpricks of insight in an enveloping fog of misapprehension’, and by the early 19th century the Egypt of the pharaohs was still largely buried in the sand. The word ‘Egyptology’ did not exist.

Yet within 100 years Egypt would no longer be known as a land of biblical-classical myth but ‘the crucible of great feats of artistic and architectural achievement’, thanks to what Toby Wilkinson calls a ‘golden age of scholarship and adventure’ — between Champollion’s decipherment of hieroglyphics and the discovery of King Tut’s tomb in 1922.

The men (and very occasionally women) who undertook this work were a colorful mix of often amateur collectors, ethnographers, antiquarians, archaeologists and treasure-hunters, including the sometime circus-strongman Giovanni Belzoni, the consumptive Lucie Duff-Gordon (who lived atop the Luxor temple) and the Prussian scholar Karl Richard Lepsius, who first wrestled the subject into some sort of academic discipline.

The great British Egyptologists ‘tended to come from unexpected quarters’. John Gardner Wilkinson arrived in Egypt on the Grand Tour and accidentally became the world’s foremost authority on its ancient history; Flinders Petrie had never been to school, was inspired by the quackish astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth, and worked outdoors in vest and pants; E.A. Wallis Budge was possibly the illegitimate son of Gladstone. But none of them beat France’s Auguste Mariette, who was apprenticed to a ribbon-maker, died as director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service and now rests in a sarcophagus in front of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Not everything was wonderful, of course. A Major Vyse used dynamite and boring rods in explorations of the Giza plateau. And then there were the variously ‘interested’ financial backers: Carnarvon, Amelia Edwards, Theodore Davis and Rockefeller. Plus all the theologians, freemasons and other assorted pseudo-scientists, only accidentally putting the last nail in the coffin of Old Testament literalism while clinging — in the era of steam locomotion, daguerrotype and telegraph — to the idea that the Earth had been created in 4004 BC.

Wilkinson’s characters were no hobbyists, however. James Henry Breasted introduced photography as the principal method of recording inscriptions. Arthur Weigall wanted to slow down archaeological exploration to allow time for skills and methods to improve. Howard Carter literally electrified the Valley of the Kings before he metaphorically electrified the world with his discoveries. Perhaps half a dozen of them have been called, for various reasons, the ‘founders of Egyptology’.

Nor were they unsympathetic to their fellow men. The young Champollion petitioned the neo-pharaonic Khedive to educate his peasantry; Petrie trained the Kuftis to be ‘skilled archaeological labor’ and Gaston Maspero wanted the Egyptian Museum to be for Egyptologists and Egyptians alike.

They dressed in native garb, slept in tombs, endured dysentery, fire, brigandage and mice. They immersed themselves in study and led dedicated and largely well-intentioned lives, to find ex oriente, lux. (For more on this, see Chris Naunton’s elaborately illustrated Egyptologists’ Notebooks, recently published by Thames & Hudson.)

By default, yes, all their careers unfolded against the backdrop of (if not hand-in-glove with) the imperial geopolitics of the age; and ‘ostensibly scholarly activities also served, wittingly or unwittingly, to open up Egypt to western involvement’. From Roman times, the possession of an obelisk —and later a university Chair in Egyptology — marked out European countries (and then America) as among the historical elect. But it is nonetheless a fact that without this particular strand of dead white males there would now be no Egyptology.

Against the depredations of the modern world, the recording (let alone saving) of the artifacts of ancient Egypt, was from its inception a race against time — not least in terms of the Egyptologists’ own lifespans. Sir Frederick Henniker remarked sharply that ‘buildings that have hitherto withstood the attacks of barbarians will not resist the speculation of civilized cupidity, virtuosi and antiquarians’.

[special_offer]

But however rightly Henniker condemned the unedifying behavior of his countrymen, the Egyptians — in the tart words of Budge — had been robbing tombs since the day after they were sealed. Under Muhammad Ali’s fast-industrializing government, structures which had captivated foreign visitors since Herodotus were being torn down to feed lime kilns and dynamited for saltpeter factories. By 1828 the monumental Napoleonic Description de l’Égypte already contained the only trace of 13 temples which had been destroyed. Ali himself gave obelisks away as gifts.

Even the noisily progressive Weigall said the Egyptians ‘care not one jot for their history’. In something of an irony, then, it was ultimately the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb (the contents of which went to the Egyptian Museum, NB) which reignited and legitimized the proud Egyptian nationalist movements of the 20th century.

It would be hard to overstate the excellence of Wilkinson’s storytelling — and I was surprisingly distraught to think that there can never be a sequel. For three years at the beginning of this century I worked — happily, if somewhat fitfully — in an institute named for one of the men in this book, yet those archaeologists’ day-to-day lives were entirely absent from my course. Late on in A World Beneath the Sands I realized what I should probably have studied was not Egyptology but Egyptologists.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.