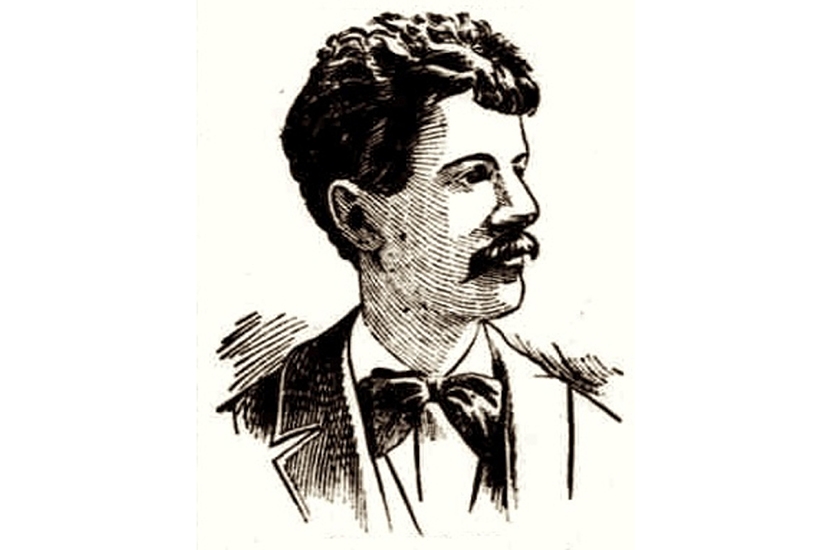

In 1886 the British mathematician and schoolmaster Charles Howard Hinton presented himself to the police at Bow Street, London to confess to bigamy. A theorist of the fourth dimension, he had looked destined to forge a career that would align him with the most renowned academic figures of the age. Now, with a conviction, a brief imprisonment, and ‘illegitimate’ twin sons attached to his name, his reputation was ruined. Unable to find employment, he fled with his first family to Japan.

Mark Blacklock’s novel tells us what happened next. We initially encounter Hinton at Yokohama harbor where, with his four sons and his first wife, Mary, he is about to board ship to America. Following his arrival, we see him secure a post as mathematics instructor at the College of New Jersey, serve at the US Naval Observatory’s Nautical Almanac and later join the staff of the US Patent Office. In his spare time he publishes science fiction, essays and monographs, and develops a gunpowder-fueled baseball cannon.

While these developments are taking place, Blacklock introduces us to the strange world of Hinton’s heart and mind, and chronicles the thoughts and deeds of the many members of his two families. He does so by drawing on a number of missives sent to Hinton by his late father (himself an enthusiast for polygamy), and by making use of a cache of gossipy letters that were circulated in the wake of Hinton’s conviction. As we accompany the mathematician on his quest to redraw his life in the shadow of disgrace, we share in his desperate longing for his second wife, Maud; in his concern for the fortunes and misfortunes of their sons; in the unhappy marriage he continues to pursue with Mary; and in the confluence of events that would lead to Mary’s suicide in 1908, a year after Hinton’s own sudden death.

Blacklock’s handling of this story is elegant and tender — ‘William had been named for Howard’s beloved younger brother, a promising student and gentle soul, overcome by pulmonary paroxysm in his 15th year’ — even if his enthusiasm for diagrams and typographical oddities can be gimmicky, and his many philosophical digressions distracting. On the whole, Hinton is a refreshing, unusual and enriching tale of ‘sadness and scandal’ that, in its capacity for imaginative compassion, manages to find something ennobling in both.

This article was originally published in

The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.