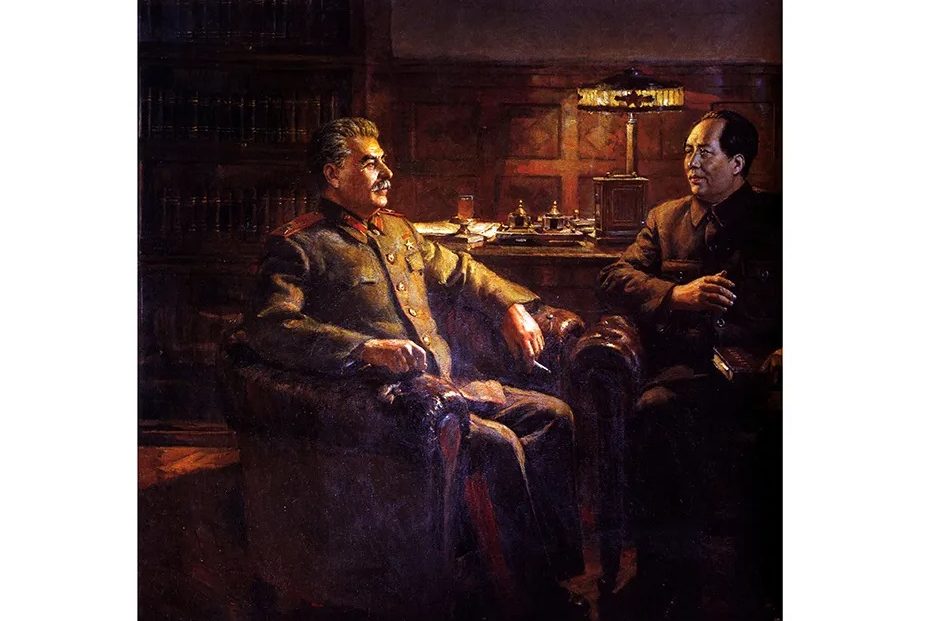

Why should we want to read yet another thumping great book about the collapse of the Soviet empire? In To Run the World, Sergey Radchenko attempts an answer. Based on recently opened Soviet archives and on extensive work in the Chinese archives, it places particular weight on China’s role in Soviet policy-making. The details are colorful. It is fun to know that Mao Zedong sent Stalin a present of spices, and that the mouse on which the Russians tested it promptly died. But the new material forces no major revision of previous interpretations.

Perhaps the book is best seen as a meditation on the limitations of political power. Stalin and his successors were trying to pursue what they thought of as the national interest — a slippery concept which even our own “realists” find hard to define in practice. At the same time, they sought to balance the conflicting requirements of leading world communism and being a great power.

At home, in Europe and in the Third World, which the Soviets saw as the most promising arena for their competition with the capitalist-imperialists, their successes in pursuing their contradictory objectives were often matched by failure. Their efforts were undermined by personal ambition, a shaky grasp of the facts and sheer incompetence. They were no better at planning for the future than the bourgeois democrats they affected to despise. Henry Kissinger once commented that Richard Nixon acted as if he had an election next year, but Leonid Brezhnev as if he had an election every week. And autocrats, too, are continually knocked off course by unforeseen events.

Radchenko deals neatly with another common source of misapprehension. Western analysts of Soviet behavior began with a fixation on ideology. I was told on joining the British foreign office in 1955 that you only had to read the abstractions of Marx and Lenin to know what Stalin or Khrushchev were going to do next. The analysts eventually came to wonder if ideology had much influence at all. Radchenko’s own conclusion can be formulated thus: ideology worked as a comfort blanket. Stalin believed that his country would eventually ride through to historical victory on a wave of scientific Marxism. So did his successors — even Mikhail Gorbachev, until near the end. But we should not preen too much. Western leaders also befuddle themselves with misty ideas about national destiny and such like. Policy-making everywhere has its own logic, as Radchenko says.

An obsession with credibility and recognition was equally important in shaping the inconsistencies of Soviet policy. Fyodor Dostoevsky was far from being the only Russian to believe that his country’s manifest destiny was to lead the nations of the world to a better future. But Russians also suspect that outsiders still regard them and their country as no more than “a complete despotism… inhabited by vicious and drunken savages,” as the Encyclopaedia Britannica said in 1782. No wonder that Russia’s despots — Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, Stalin and now Putin — have always insisted on their right to respect.

World War Two had a tremendous emotional effect on Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev and all their contemporaries. It still does. Putin manipulates these emotions for his own ends. But his constant invocation of the victory is more than mere propaganda. Stalin was determined to exploit the fruits of that victory. They faded within two decades. Neither the erratic Khrushchev nor his cautious successor Brezhnev could reverse the decline. Gorbachev was a decent man with revolutionary ideas for change. He combined with Ronald Reagan to end the Cold War in a last splutter of Soviet-American co-operation. But it was under him that the Soviet system finally collapsed of its own weight.

Radchenko frets incessantly about the what-ifs. Could the Cold War have been averted if Stalin, Churchill or Truman had behaved differently? Could Eastern Europe have been saved from tyranny? Could the Soviet collapse have been postponed or averted by a more ruthless Soviet leadership? Could the present catastrophic relationship between Russia and the West have been avoided if the Americans had been less arrogant towards their defeated opponents?

And the future? Khrushchev worried that Mao would steal his thunder. Brezhnev believed he and Nixon could rule the world together. Putin seems to have forgotten all that, as his brutal war with Ukraine destroys Russia’s relationship with the West and he maneuvers his country into a subordinate position under a resurgent China.

The evidence is never clear cut. There are no killer facts, only speculation. Radchenko knows that, but his successors won’t be deterred from writing their own massive books. And why not? Stories about the decline and fall of empires will always find an audience. Just look at the profit and pleasure we all get from reading Mary Beard.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply