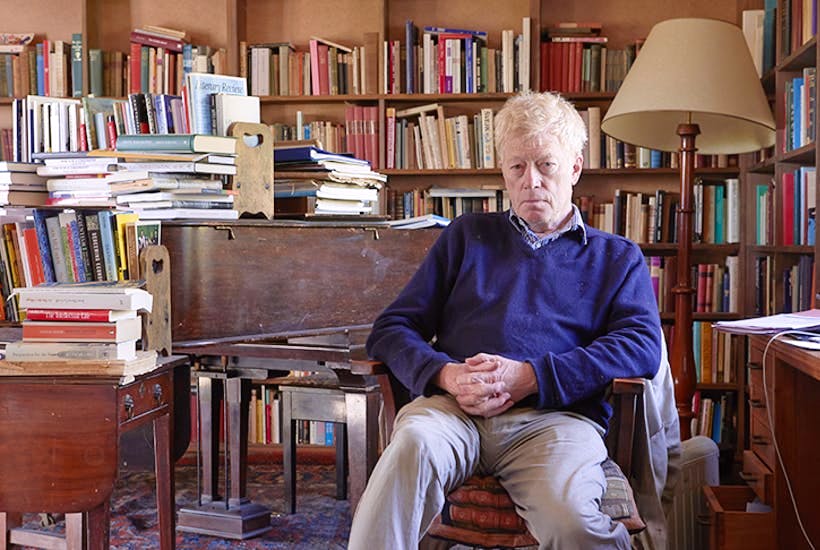

Sir Roger Scruton has died. Diagnosed with cancer last summer, he passed away peacefully on Sunday surrounded by his family.

There will be a lot of things written and said in the coming days. But perhaps I could say a few things here.

The first is to reiterate something that the Scruton family have said in their announcement of his death. There they refer to how proud they are of Roger and of all his achievements. I think I can say that all Roger’s friends share that feeling. His achievements were remarkable. He was a man who appeared to know about absolutely everything, producing books on architecture, philosophy, beauty, music, religion and much more. In many ways — as his former student Rabbi Sacks once said to me — he seemed bigger than the age.

There seemed no area he had not mastered. In the mid-2000s we were at a dinner party at the house of our late friend Shusha Guppy with a group of eminent writers and journalists, all with egos of their own. I remember one of them asking Roger whether he would think about doing an updated version of his book The West and the Rest. With characteristic and by no means feigned humility he replied that he didn’t think so because he didn’t think his Farsi was any longer up to it. How beautiful it was to see every other writer in the room look as though they might just give up there and then.

Doubtless there will be some talk in the coming days of ‘controversy’. Some score settling may even go on. So it is worth stressing that on the big questions of his time Roger Scruton was right. During the Cold War he faced an academic and cultural establishment that was either neutral or actively anti-Western on the big question of the day. Roger not only thought right, but acted right. Not many philosophers become men of action. But with the ‘underground university’ that he and others set up, he did just that. During the Seventies and Eighties at considerable risk to himself he would go behind the Iron Curtain and teach philosophy to groups of knowledge-starved students. If Roger and his colleagues had been largely leftist thinkers infiltrating far-right regimes to teach Plato and Aristotle there have been multiple Hollywood movies about them by now. But none of that mattered. Public notice didn’t matter. All that mattered was to do the right thing and to keep the flame of philosophical truth burning in societies where officialdom was busily trying to snuff it out.

Having received numerous awards and accolades abroad, in 2016 he was finally given the recognition he deserved at home with the award of a knighthood. Yet still there remained a sense that he was under-valued in his own country. It was a sense that you couldn’t help but get when you travelled abroad. I lost count of the number of countries where I might in passing mention the dire state of thought and politics in my country only to hear the response ‘But you have Roger Scruton’. As though that alone ought to be enough to right the tiller of any society. And in a way they were right of course. But the point did always highlight the strange disconnect between his reputation at home and abroad. Britain has never been very good with philosophers of course, a fact that Roger thought partly correct, but his own country’s treatment of him was often outrageous. As events of the last year reiterated, he might be invited onto a television or radio program or invited to a print interview only for the interviewer to play the game of ‘expose the right-wing monster’. The last interview he did on the Today program was exactly such a moment. The BBC might have asked him about anything. They might have asked him about Immanuel Kant, or Hegel, or the correct attitude in which to approach questions of our day like the environment. But they didn’t. They wanted cheap gotchas. That is the shame of this country’s media and intellectual culture, not his.

But if there was a reason why such attempts at ‘gotchas’ consistently failed it was because nobody could reveal a person that did not exist. Of course Roger could on occasion flash his ideological teeth, but he was one of the kindest, most encouraging, thoughtful, and generous people you could ever have known. From the moment that we first met – as I was just starting out in my career — he was a constant guide as well as friend. And not just in the big things, but in the small things that often matter more when you’re setting out. Over the years I lost count of the number of people who I discovered that he had helped in a similar way without wanting anyone to notice and expecting no reward for himself.

A man other than Roger might have got bitter about some of the treatment he received, but he never did. Whatever his complex views on faith, he lived a truly Christian attitude of forgiveness and hope for redemption. His last piece for The Spectator — a diary of his last year — radiates this. If he sometimes fitted uncomfortably with the age in which he found himself it was principally because he did not believe in its guiding tone of encouraged animosity and professionalized grudge. He believed instead – and lived in — the spirit of different age. One in which he encouraged his readers to share. That is a spirit of gratitude for what you have received, and forgiveness for what you have not.

One of my first grieving thoughts on hearing the news was how much I still had to ask him. But in that spirit which he encouraged I will instead turn to the shelves I have full of his books and marvel again instead about the huge amount he gave us.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.