Pity the security guard at the Guggenheim who must patrol the gallery in which Robert Rauschenberg: Life Can’t Be Stopped is installed. Mounted in commemoration of the artist’s centennial – Rauschenberg was born in Port Arthur, Texas, in October 1925 – Life Can’t Be Stopped includes “Revolver II” (1967), a set of plexiglass discs with images overlaid. A cord leads from the back of this contraption to a pedestal on which there is a control panel – a set of buttons placed in proximity to the viewer. These switches set the plexiglass discs in motion, and they beg to be pushed. On my trip to the museum, visitor after visitor was shushed away from “Revolver II” with the age-old plaint: “Please don’t touch the art.” We were informed that a designated button-pusher would do the honors at unscheduled times during the day. What fun is that?

That dour, party-pooping spirit pervades this 100th birthday fête. The Guggenheim extols Rauschenberg as a figure “whose influence on contemporary art remains immeasurable.” Maybe so, but what good has that influence been?

As part of the festivities, a one-night event included performances by the dance companies of Trisha Brown and Paul Taylor, choreographers for whom Rauschenberg provided stage settings. For Taylor, Rauschenberg created “Tracer” (1962), a spinning bicycle wheel here accompanied by music by James Tenney. “Tracer” is an obvious homage to “Bicycle Wheel “(1916-17), a ready-made object by the grandpère of anti-art, Marcel Duchamp.

Rauschenberg’s oeuvre is inconceivable without the example set by Duchamp, a cigar-smoking gadfly whose specialty was upsetting the preconceptions of a cultural elite that he was very much a part of. The irony is that the dadaist kingpin had an eye sharp enough to realize that he possessed neither the imagination nor the gumption to compete with such contemporaries as Brâncuşi, Matisse and Picasso. The Duchampian corpus is small: he spent much of his life playing chess. Rauschenberg does not possess any similarly redeeming self-awareness. Duchamp lived to see a younger generation take inspiration from a mode of artmaking specifically contrived to undermine it. Did he take pride in his progeny? Hardly: Duchamp was skeptical of their efforts. Neo-dadaists, he averred, were taking “an easy way out.” He had thrown a bicycle wheel and a urinal into the establishment’s face “as a challenge, and now they admire them for their aesthetic beauty.”

Nose-thumbing is irresistible and can be profitable in an art market that often mistakes provocation for aesthetic worth. Every time a stray wit duct-tapes a banana to a wall and calls it art (see “Comedian” by Maurizio Catellan), a line can be traced to Duchamp. Before it reaches Duchamp, however, that line would run through Rauschenberg, the man who made anti-art safe for mass consumption. Dada with a smiley face – Bob’s our man.

The die was cast in 1953, when Rauschenberg the precocious Texan erased a drawing by the painter Willem de Kooning and appropriated it as his own work, to wit: “Erased de Kooning Drawing.” A Duchampian stunt of the first order, you might think, but the gesture was not altogether nihilistic. Duchamp’s cynicism had a certain integrity; he pulled from European intellectual debates. Rauschenberg, in contrast, was as American as apple pie.

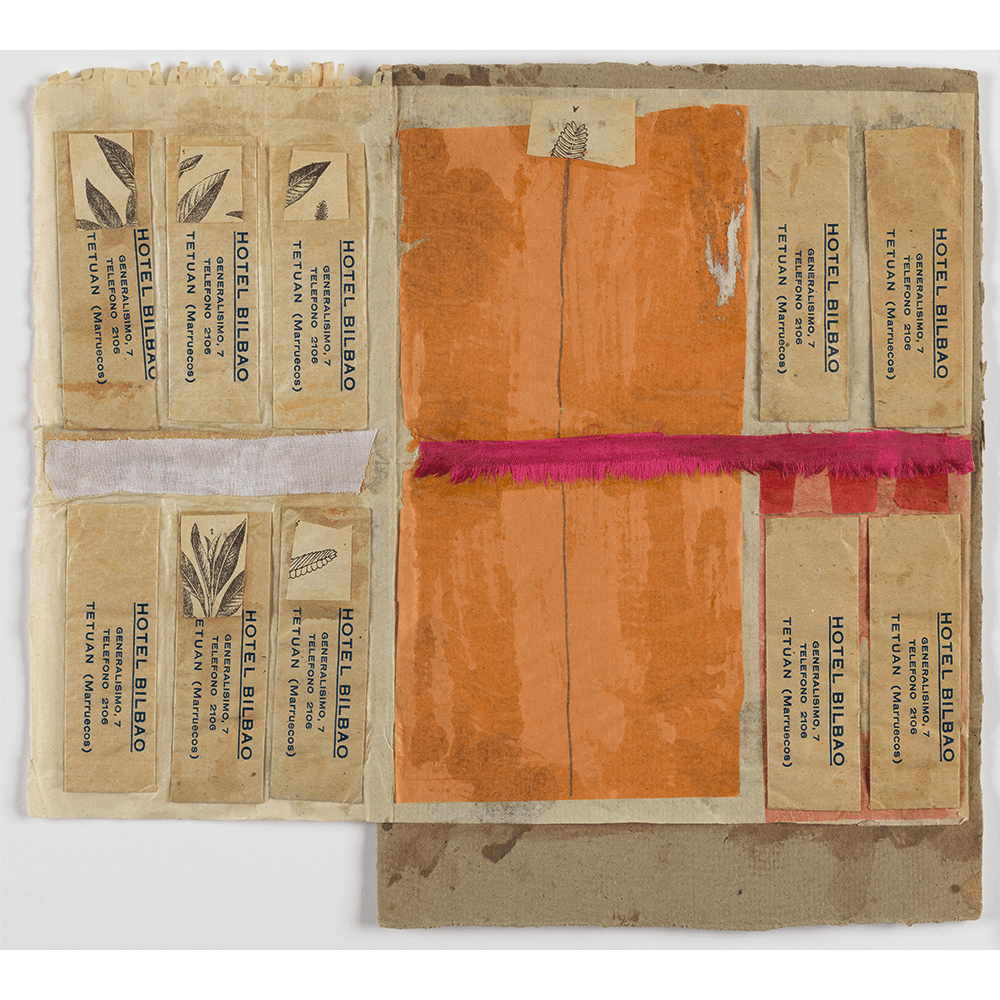

Rauschenberg’s earliest and best work is marked by a can-do positivity, a kind of free-for-all optimism that became increasingly codified as success while his small talent transformed into an international industry. The young Rauschenberg is in scant evidence at the Guggenheim, though pieces such as “Untitled (Red Painting)” (c. 1953) and “Untitled (Hotel Bilbao)” (c. 1952) evince a rough-hewn approach to materials gleaned from the German collage artist Kurt Schwitters. A sense of play and, at moments, a sort of tenderness is palpable.

Rauschenberg’s initial efforts at drawings made with solvent transfer – a process whereby printed materials are applied to a surface by soaking them with water and chemicals – were similarly endowed with a promiscuous curiosity and scope. But once he got a handle on this method, it became considerably less winning. Rauschenberg coasted on its second-hand appeal, submitting a surfeit of grainy news photos to grid-like superstructures and then punctuating them with brushwork mimicking the rough-and-tumble verities of abstract expressionism. “Expert,” this kind of thing is called again and again; over the long haul, it is deadening.

The centerpiece of Life Can’t Be Stopped is “Barge” (1962-63), a black-and-white canvas that measures five feet high by a whopping 32 feet in width. Completed in a 24-hour period, this piece found Rauschenberg adopting a commercial printing technique introduced to him by Andy Warhol. Time isn’t necessarily an indicator of aesthetic worth – better works have been made in fewer hours – but taking advice from Warhol only brought out the worst in Rauschenberg. Tactility and enthusiasm were subsequently sacrificed for efficiency. The resultant diminution of material and aesthetic necessity is fatal.

As it is, “Barge” is a glibly articulated compendium of diagrams, football-game footage, photos of space vehicles and – should these items not be arbitrary enough – a reproduction of “Venus at Her Mirror” by Diego Velázquez. “This monumental piece,” the Guggenheim tells us, “makes its highly anticipated return to New York for the first time in nearly 25 years.”

Public-relations hyperbole is one thing, but it’s doubtful that a work as dead-on-arrival as “Barge” is capable of prompting a response from even the most ardent Rauschenberg fan. There are better ways to celebrate a birthday than Life Can’t Be Stopped.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply